My earliest consciousness of a country named Egypt came from visits to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art when I was a child. The Egyptian wing, with its jewel-encrusted death masks, evocative art, and reproductions of great stone temples held me captive. Howard Carter and George Herbert’s well-publicized discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb took place 14 years before my birth, but the extraordinary find, complete with its mysterious “curse,” periodically filled the newspapers of my youth. When the exhibition of the young king’s royal paraphernalia came to the US, I was one of millions who thrilled to its riches.

I probably didn’t think much about Egypt again until the 1980s, when I taught Nawal El Saadawi’s moving book, Woman at Point Zero in a literature class at a US university. El Saadawi is an Egyptian novelist, medical doctor and activist on behalf of women’s rights. Early in her career she became her country’s Director of Public Health, and her efforts on behalf of women and others eventually cost her that position as well as several imprisonments under the Sadat regime. Woman at Point Zero was written after interviewing Firdaus, a poor woman sentenced to death for having killed a pimp. As she tells El Saadawi her story, it becomes clear that she welcomes death as a release from a lifetime of poverty and hardship. This was a very different Egypt from the one I had thrilled to so many years before.

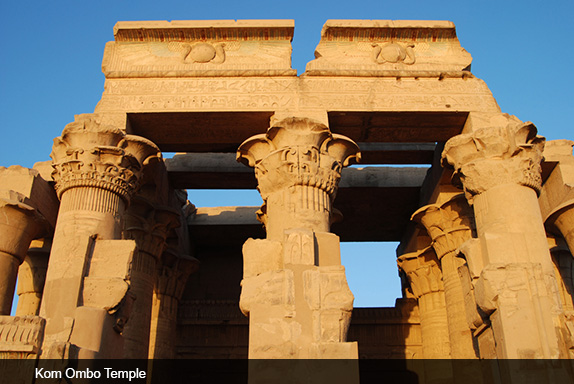

In 2006, my partner and I traveled to Egypt. The so-called Arab Spring was still four years into the future, and as unexpected (some would say unimaginable) as any near-future event. Our trip was one of those two-week tastes: a few days in Cairo where we visited the pyramids at Giza and the fascinating but extremely cluttered and dusty Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, strolled through the spice market with its heady scents and insistent merchants, and often got stuck in the city’s monstrous traffic for more than an hour at a single stoplight. We visited some of the country’s extraordinary temples, among them Edfu, Kom Ombo, Luxor and Abu Simbel. A few years before, several tourists had been gunned down by snipers at the tomb of Queen Hatshepsut (1479 - 1457 BC), so that site was not on our itinerary. Barbara and I went off on our own to see it.

The Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens were surprising in their beauty and mystery, especially the well-preserved richness of many of the frescoes within their depths. The Ramasseum was another amazing experience. The shear size and architectural power of these temples was hard to fathom, each so different from the others. More humble constructions also awed us, such as the multi-colored adobe houses in a Nubian village near Aswan and the home of Hassan Fathy, the architect who built the adobe-domed mosque near Abiquiu, New Mexico. His daughter, who welcomed us to the house, got quite excited when she discovered we had been to the mosque her father built in our state.

We spent half our visit in a houseboat on the Nile, the only river in Africa that flows north rather than south and that has been Egypt’s lifeline for millennia. The narrow valley of fertile land on either side is like a ribbon of life in the desert. And that desert, hundreds of miles of shifting sand dunes called the Sahara, should be a warning to all of us; it is now believed to have been created by climate change and/or overgrazing around 8,000 BC.

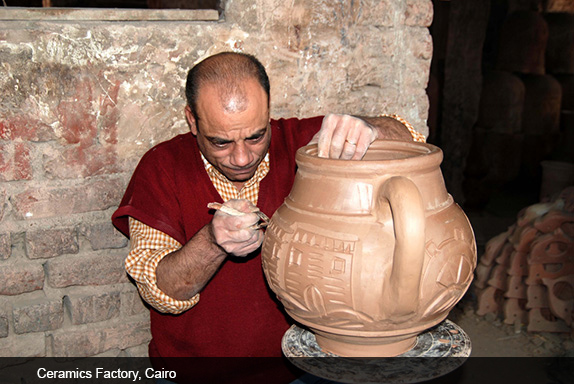

Motoring up the Nile we visited many villages and cities, viewed farmers, fishermen in their graceful feluccas, and women washing their colorful rugs along the shore. We went to rug and ceramics factories, wandered the beautiful old center of Cairo, and sat through a touristic rendition of their characteristic religious dance by a group of whirling dervishes. In Aswan, we stayed in the hotel where Agatha Christie wrote Death on the Nile. Our time in the country also included a few experiences most tourists don’t have, such as sharing dinner with a family in Cairo or shopping for the ingredients to cook our own Egyptian meal—with only a marketing list written in Arabic, a handful of money given us by our guide, and what sign language we imagined might be recognizable to the salespeople in the stalls. A highlight was a visit to a heart-warming school for children with physical disabilities in the city of Luxor. Parents were being taught to exercise their sons and daughters, and clearly were proud of their offspring, holding them up for us to photograph. Classrooms were mixed, the physically disabled children mainstreamed along with students without disabilities.

The timing of our trip turned out to be unique. On our flight over we coincided with hundreds of travelers headed to Mecca on their once-in-a-lifetime Hajj, the trip required of all devout Muslims. Fellow airline passengers prayed in the aisles, and the plane’s restrooms were drenched from their pre-prayer ablutions. And the morning we left Cairo again for home, we noticed that people in both our hotel dining room and the airport seemed unusually quiet. We soon found out that Saddam Hussein had just been executed in Baghdad.

It was a lot for two weeks, and of course much too little to glean anything but an outsider’s view of the country. I was saddened not to have been able to get to Alexandria, whose library was the only one of its kind for centuries. I came home with a jumble of impressions. But I felt that we had seen and learned a great deal. I was both in love with Egypt and harassed by some of the things I had experienced, especially as a woman.

This latter mostly had to do with the aggressively insistent attitude of people selling things in the markets or on the street. At first I excused this aggression, telling myself that in such extreme poverty people did anything they could to make a sale. But the day I found myself literally trapped inside a market stall, with a man twice my size blocking the door, presumably until I purchased something I didn’t want, the custom began to grate. I wondered at how generations of injustice and misery had turned one segment of the Egyptian population into ferocious madmen. Of course I had been assailed by overeager salespeople in other parts of the world, but never so consistently or overbearingly.

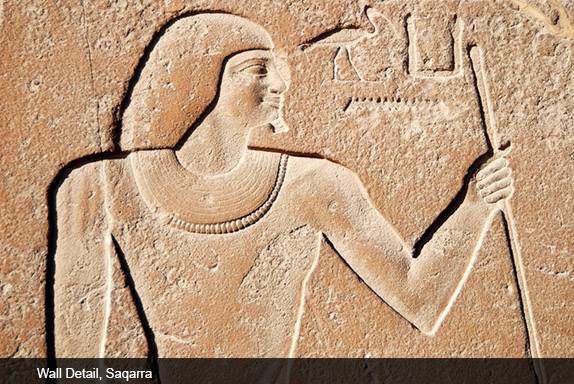

Egypt’s culture is one of the oldest known. From the tenth millennium BC, there is evidence of rock carvings along the Nile. By about 6,000 BC, a Neolithic people were making the Nile valley their home. Pre-dynastic cultures developed independently in what came to be known as Upper and Lower Egypt. King Menes founded a unified kingdom around 3,150 BC, and this initiated a series of dynasties that ruled the country for the next 3,000 years. The Old Kingdom ran from 2,700 to 2,200 BC. The great pyramids at Giza were built during this time. The Middle Kingdom dated from 2,040 BC. With the New Kingdom, 1,550 to 1,070 BC, Egypt began to be a world power. This period is known for some of the most famous Pharaos, such as Hatshepsut, Akhenaten and his beautiful wife Nefertiti, Tutankhamun and Ramesses II.

The thirtieth in this succession of dynasties was the last of native rulers. Egypt fell to the Persians in 343 BC. The Greeks gained influence with the installation of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. The last ruler from the Ptolemaic line was Cleopatra VII, the much-storied queen who committed suicide following the death of her lover, Mark Antony. He in turn had died in her arms from a self-inflicted knife wound, choosing death over surrender. This led to Egypt’s domination by another great power, Rome. Later there was a Muslim conquest, then Christianity (brought into Egypt by St. Mark the Evangelist in the first century AD), and Diocletian’s reign, opening the door to the Byzantine era. After the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, the Egyptian Coptic Church was established.

But the Muslims regained power, bringing Sunni Islam to the country, and it was to remain in control for the next six centuries. Under the Fatimids, the Mamluks, a Turco-Circassian military caste, took power, and by the late 13th century Egypt linked the Red Sea, India, Malaya and the East Indies. The Mamluks continued to govern until the Ottoman Turks took over in 1517. This was the beginning of the Ottoman Empire.

Europeans invaded Egypt, beginning with Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798. Ottomans, Mamluks and Albanians wrestled for power. Out of this chaos, the commander of the Albanian regiment, Muhammad Ali, emerged as the dominant figure, and in 1805 was acknowledged by the Sultan in Istanbul as his viceroy in Egypt. Muhammad Ali established a new dynasty and was able to rule the country until the revolution of 1952. The British were nominally in control, but strong Egyptian leadership imposed its own rules.

Before the turn of the twentieth century, Egyptian cotton had gained enormous value on the world market, promoting a cash-crop monoculture and concentrating native and foreign land ownership. By 1953, when the Egyptian Republic was founded, a series of strongmen began to succeed one another at the helm. Gamal Abdel Nasser assumed the presidency in 1956. British forces completed their withdrawal from the occupied Suez Canal zone. Nasser’s nationalization of the Canal prompted the Suez Crisis remembered by those of my generation.

In 1958, Egypt and Syria formed a sovereign union called the United Arab Republic. It was short-lived, ending when Syria seceded in 1961. A detailed history of Egypt’s alliances and crises over the following decades is beyond the scope of this piece. During the 1967 Six Day War, Israel invaded and occupied Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip, occupied by Egypt since the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. As a result of these maneuverings, Egypt has long been the Arab nation in the best position to act as a go-between for the Israelis and Palestinians and maintain some degree of peace in the region. Anwar Sadat, who succeeded Nassar in the presidency, switched the country’s Cold War allegiance from the Soviet Union to the United States. In 1981, a fundamentalist soldier assassinated Sadat, and he was succeeded by Hosni Mubarak.

Clearly, this long line of rulers did little for the quality of life enjoyed by ordinary Egyptians. In 2003, the Egyptian Movement for Change, popularly known as Kefaya, was launched to oppose the Mubarak regime and to establish democratic reforms and greater civil liberties. When, three years ago, the Arab Spring took the world by surprise, those who had been fed disconnected bits of “news” by the international corporate media were shocked—and perhaps falsely encouraged—by the rapidly escalating events.

What we called the Arab Spring had begun in Tunisia and quickly spread to Egypt before also engaging other countries in the area. In Egypt, thousands, then millions gathered in Cairo’s Tahrir Square and other public plazas. Young people used the Internet and cellphones to rally supporters. They spoke of “days of rage,” the term we used in the 1960s for similar demonstrations of protest. It took less than a month for Mubarak to lose control, and on February 11th he resigned.

But rather than people’s power, it was the military that stepped in and took over. A constitutional referendum was held on March 19th, and on November 28th Egypt held its first parliamentary election in what have been called democratic conditions. Mohamed Morsi became the new president and made strides toward wresting control from the military. Over the next several years, however, he has given dangerously mixed messages to those who put him in power. As I write (July, 2013), the Egyptian military is challenging Morsi’s hold on power. Millions of people are once again in the streets and squares, determined to wrest real freedom from their leaders.

On the one hand, it is these same armed forces and police that have continued to put down popular demonstrations. On the other, Morsi has given increasing power to the country’s Islamic fundamentalists. Even some members of Mubarak’s ousted government have retained a degree of influence, and many of them have remained immune to prosecution. Increasingly, ordinary Egyptians are saying they will not tolerate the authority of one faction or another.

Life for ordinary people has not changed much. Women, especially, who played an active role in the movement that toppled Mubarak, have seen their dream of equality ignored or ridiculed. On International Women’s Day, March 8th 2012, groups of women returned to Tahrir Square with placards demanding their rights. Many were attacked by the same men who had been their comrades at the barricades months before. Some of the women protesting were seriously injured, and all expressed their amazement and dismay that the revolution had not really been for them. A US television reporter was attacked at one of the ongoing demonstrations and sexually assaulted; only the appearance of other, saner, Egyptian men saved her from being mauled to death.

Political unrest, stemming from unfulfilled promises and an Islamic fundamentalist-secular tug of war, continues to wrack this most influential of Arab states. Egypt is a combination of contemporary turmoil, exquisite landscape, fascinating traditions, and ancient treasures too vast to be seen on several trips.

Responses to “Friday Journey: Egypt”