Several weeks ago, I wrote about the state of my prostate. The results are in. It turns out that I, despite all of my years spent eating Flintstones vitamins, am not a qualified health-care professional.

One concerned reader noted that a wellness checkup for men, an important component of keeping doctors in business, is not prostate cancer PREVENTION but rather prostate cancer DETECTION. I stand corrected, albeit a bit bowlegged after running myself through so many fruitless background checks. And my friend Andy, who is training to be a real doctor, wrote me to say that “as a medical semi-professional, I can say with confidence that you’re too young to need your prostate checked for anything other than recreational purposes.”

Despite such assurances, I did not cancel my scheduled wellness checkup, because it was tougher to get than a Tickle-Me Elmo. (Which, now that I think about it, is pretty much what I was looking for.) And if I, a white male with extreme medical concerns, could barely get a doctor’s appointment before the end of the next Clinton presidency, I knew that untold other American citizens must be dying out there.

Which they are—nearly seven thousand every day. That’s one whole person for every 219 Big Macs sold. When I was born, I did not sign up for a world where people die. Namely, I did not sign up for a world where I could die.

If healthcare wasn’t going to make me invincible, then by gum, I would. I’d already taken matters into my own hands—what I now refer to as “private DETECTION.” That didn’t work. So it was time to take matters into my own mouth.

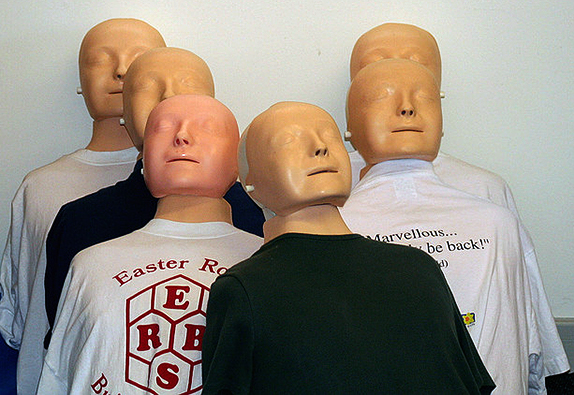

That’s right: I learned CPR. But before you rush out to take CPR classes of your own, you should know that CPR is worthless. Even if you are fully certified, you cannot save your own life. Even so, I stayed for the entire class, because they provided snacks.

And I’m glad I did, because now, should the top half of a mannequin ever collapse to the floor and prove unresponsive—you would be surprised how often this happens, even in a first-world nation—I am trained to provide it with chest compressions and emergency breathing until an instructor calls time.

Ultimately, the class gave me something much more meaningful than a CPR certification card. It endowed me with the skills and the confidence to go into any dangerous, high-stress situation and imagine an even more dangerous and stressful situation.

I honed these abilities during the simulations in class. We students concocted difficult scenarios with plenty of hazards, in order to heighten the challenge of giving CPR to a dummy. My finest creation involved a bicycle, bucking horses, an overturned eighteen-wheeler, four dozen youth basketball campers, and a prominent international figure. Doctor-patient confidentiality, not to mention word count, prevents me from describing whether emergency breathing saved the astronaut after her crash landing.

Destroying lives in order to attempt saving them was the most enriching four hours I spent that afternoon. I awaited my own doctor’s appointment with an invigorated appreciation for medical practitioners. My doctor and I were basically colleagues now. Peers! Equals in every way, except I wasn’t open to malpractice suits.

I simply had to see my comrade-in-medicine right away, before anyone revoked my CPR certification. I petitioned the nurses until they canceled someone’s appointment to slot me in. But lest you get as enthused as I was, I must tell you that a doctor’s practice is a really dull way to save lives. Their processes may work fine in theory, but in reality they are much less exciting than your average warrantied toaster oven.

I’m not questioning whether these professionals know what they’re doing. All I’m saying is that when the nurse took my pulse, she did not even attempt to invent a life-threatening hazardous situation. Doing so would be SUPER EASY. Heck, I invented dozens of maladies in the waiting room while filling out the eighty-page medical history questionnaire.

Then the real doctor finally came in. She was a no-nonsense professional who wasted zero time asking me every question I had just answered on the questionnaire. She deemed my responses honest without even running a psych eval or checking if my fingers were crossed, then declared me healthy anyway and sent me out the door.

Oh, sure, she looked up my nose and put her cold stethoscope on my back. Boooooorrrring. I look up my own nose every day! So the lesson is, if you want some real medical drama in your life, yell for CPR in a circus tent frequented by schoolchildren and dignitaries, and then collapse. And if you want the serious recreational hijinks, make an appointment with Andy. He’s almost as certified as I am.

(Photo by John Haslam / CC)

Responses to “Fool’s Gold: Medicine for Dummies”