After her first New Mexico legislative session in 1997, Sen. Dede Feldman said it was “like riding a motorcycle in a thunderstorm in the nude.”

When she left the Senate 16 years later, the liberal Democrat from Albuquerque’s North Valley still felt like “Alice in Wonderland” in this “crazy unpredictable place” dominated by “peculiar personalities [and] strange alliances.”

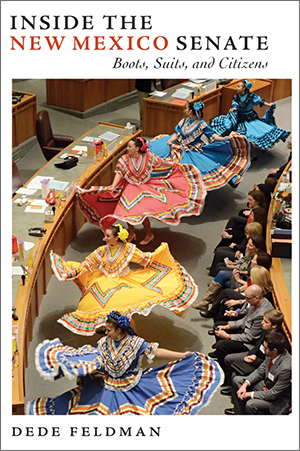

These and dozens of other extraordinarily frank recollections of her legislative service appear in Feldman’s book published this month by UNM Press, Inside the New Mexico Senate: Boots, Suits and Citizens.

This is the most honest book I have ever read about how the Legislature really works. I covered it in the late 1970s and early 1980s for several newspapers, magazines and KUNM public radio, and I have frequently revisited it. I recognize her analysis and reporting as pure truth. It is a book that should be mandatory reading in every course on New Mexico politics.

Most books about state government mix generalities, homilies, a few innocuous anecdotes, and descriptions of how legal and constitutional provisions theoretically work. Even the recent books by the redoubtable Gov. Bruce King and the admirable Sen. Pauline Eisenstadt did not dare to break this mold.

But Feldman does dare, and in the process has produced a well written account (she is a former freelance writer and investigative reporter) of her legislative experiences that is as entertaining as it is instructive. It is also, I must add, pretty thoroughly disheartening.

Unlike most such “insider” accounts, she has the fortitude to name names. The senators who make idiots of themselves or of their constituents do not remain anonymous.

Although there are a few good men and women in the Legislature, and a lot more who would be good if they could, the system militates against both effectiveness and integrity.

Legislators draw no annual salary; have no help dealing with constituents; are restricted to an absurd 90 days of sessions every two years; have no firm ethical guidelines on conflicts of interest; and are chosen, predominantly from one-party districts that they draw themselves (35 of the 42 seats are safe from partisan challenge), in elections financed by huge contributions from groups whose interests the successful candidates will then vote on.

In recent years, two former legislators were imprisoned for bribery. Others defended spending “campaign contributions” on massages, a classic truck and sewer services.

Legislators lacking time, resources and expertise, are at the mercy of lobbyists. Every year there are seven or eight lobbyists for each legislator, offering every conceivable kind of blandishment and incentive to vote their way. California House Speaker Jesse Unruh once said of lobbyists that you had no business being in the legislature if you couldn’t eat their food, drink their booze, screw their women and then vote against them. (Feldman describes the food and booze but omits the women.)

Ethical embarrassments seem to be a way of life in this “system that is often subject to conflict of interest and corruption” When one senator wanted to abstain from a vote due to a conflict of interest, her leader told her, “We don’t do that here.”

In fact, very few legislators ever abstain no matter how directly an issue affects their families. Close to home, Rep. Rhonda King, who represented much of Edgewood and the Estancia Valley, voted with the National Rifle Association against enhanced screening of gun purchasers for mental illness although her cousin Jerry King had been a lobbyist for the NRA.

Most of the real legislative action transpires behind closed doors. “Floor debate is by turns solemn, raucous, formal, outrageous, boring and nonsensical,” Feldman writes.

The fate of very big issues—health care, taxes and capital punishment, to name only three—was decided in substantial part by who hated whom and who was who’s long-time pal. For example, the most ambitious effort at health care reform foundered on the shoals of Senate President pro tem Tim Jennings’s hatred for Gov. Bill Richardson, which started because he felt the governor slighted his wife.

The Senate, with only 42 members, is like a family, Feldman says, and with the exception of a single year it has been dominated by Democrats ever since 1933. At times the GOP membership has been smaller than the family that gathers annually around my mother-in-law’s dining table.

As is true of many a family, the quality of the relationships determines what does and does not happen in the Senate. More often than not, those relationships are dysfunctional, built on greed, competition and distrust.

There are good things to be said about New Mexico legislators. They are “remarkably open and accessible,” much more so than legislators in most other states. Traditions, including those of Hispanics and Native Americans, are honored. Many relationships between legislators are warm and of long standing.

For example, in 1977, John Pinto hitched 230 miles from the Navajo Reservation to Santa Fe. He was picked up by a Cadillac driven by a stranger, Manny Aragon. They discovered that both had just been elected to the Senate and were headed for their first session. They remained friends for a generation.

Some legislators do struggle to deal honestly with the complexity and moral conflicts of issues. Facing a vote of conscience on whether to abolish capital punishment, Rep. Tom Anderson had tears streaming down his face when he said, “I am not a bad man. This is not an easy job. It is difficult to do. I don’t like this job.”

Anyone who has tried to understand the Legislature from the outside quickly realizes how opaque its relationships are to those not in the know. Intending to praise the body that he served for years, Sen. Roman Maes may however have delivered the ultimate indictment: “This is the best, most exclusive club in the state.”

Responses to “Finally an honest book about the New Mexico Legislature”