A friend wrote the other day to tell me her novella had been published. Where can I get a copy? Here’s the link, she responded. And when I went to it I discovered her book was only available on Kindle. No hardcopy at all! This was my first experience with what I fear may become commonplace, a gradual replacement of physical books with their digital imposters, something like cloning gone wild.

Call me old-fashioned. I like to read real books, material objects with pages I can turn, a cover that draws me in, inked pages that in some cases even smell of the old bookmaking craft. I know it’s the rare book today that was produced on a letterpress with anything resembling printer’s ink. But the mass produced facsimiles, especially when well designed, allow me to make believe.

Reading is, after all, about make-believe. It transports us to distant lands, times before our own, people with whom we would not come in contact were it not for their stories preserved in print, ideas that encourage our own.

Of course I know that the electronic versions of books—the Kindle, the IBook, the Nook—deliver the same content. They can even do so ever so much more expediently. Instead of a trunk full of books you can travel with several hundred inside a small device. You can make the typeface larger or smaller depending on your eyesight or light source. And by clicking on a word or phrase you can explore its history and meaning with dictionaries, thesauruses and encyclopedias that will tell you everything you want to know.

But something’s not right. It may be about the way form and content merge for me when the vehicle delivering them does what I expect. Compare writing in the margins with making digital notes. Consider the touch of a cloth, leather or even paper cover as opposed to the cold feel of synthetics. Consider what their material essence says of papyrus scrolls, cuneiform engravings, glyphs etched into stone, or the codices of the Maya; surely their physical form is as important as what can be deciphered there. Curling up in the corner of a comfortable couch against a mash of cushions on a cold winter night almost demands a real book in hand. I understand all the advantages offered by the digital devices, but give me an old-fashioned book anytime.

Is it just that at my age I am not comfortable with progress? No. I traded my old film camera in for a digital model. I miss my darkroom but have become proficient at Photoshop. I use a cell phone and even got rid of my land line. I do a great deal of research on line, and depend on email to connect me to the world.

Obviously this begs the question of digital periodicals, such as our beloved New Mexico Mercury. Why do I value them, when digital books disappoint? I think it must have to do with the fact that I expect a periodical to be constantly changing, of the moment, immediate and relevant to the here and now. Digitally delivered news media allow for community response, sometimes even blossoming into all out discussion.

But books are where I draw the line. I hope I do not live long enough to have to say farewell to books. Could it be because I am a writer and, although I appreciate my publishers making my words available in all the different mediums, I welcome each new physical book as if it were a newborn? From cover through interior format, I delight in what their designers do with the raw material I provide. I am always eager to see how they match their talents to mine, producing something elegant and inviting.

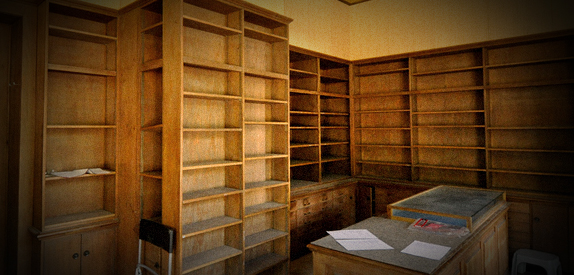

And because I love books I love bookstores, especially the independent variety that enriched our communities before the chains did them in. I could spend hours in those wonderful stores, staffed by people who knew and loved books. I never felt rushed or as if I were in some wholesale warehouse. I understood that those stores stocked titles by small specialty publishers, and that the major publishers gave preferential pricing to the chains. Through this sort of collusion our country’s taste in reading was subtly but progressively shaped to reflect the needs of a corporate, consumerist, violent and warmongering society. They would turn us into robots.

All this went hand in hand with governmental defunding of libraries and schools cutting art and music so that students could spend all their time learning to take tests and spew from memory. Teaching to think has been replaced with rote memorization. The United States’ world standing in innovation, creativity, and how well we educate our young have suffered as a result. And our “experts” still don’t seem to grasp the reasons why.

Albuquerque had The Living Batch, for decades one of the best literary bookstores in the country. It had Salt of the Earth, a marvelous general interest store that also hosted years of important readings and lectures. We had Full Circle, one of the best-stocked women’s bookstores, and then also Sisters and Brothers, a store featuring gay and lesbian literature. Trespassers William was a bookstore where children could attend weekly storytelling sessions and find the perfect book for whatever age and taste. Each of these great stores eventually succumbed to the pressure of capitalist bookselling. Today Albuquerque is fortunate to have Bookworks, a well-stocked and inviting independent bookstore that does its best to fill in for all those we have lost. We need to support it in every way we can.

A few years after the demise of so many fine independent bookstores, Barnes and Nobel and Borders—the chains that had done them in—had to compete with Amazon.com, the mega online source for everything from books to appliances. They too became victims of the changing times. Amazon.com is a phenomenon with which it’s hard to argue. I hate the corporate power it exerts over publishing and pricing, how authors and independent publishers are treated, and the sensationalist titles that are featured. I hate watching a single powerful entity control how we acquire our food for thought. At the same time, I appreciate a single site where new and used editions can be found, where at least some of the savings are passed onto the buyer, and where readers can review books. I appreciate my own Amazon.com author’s page, listing so many editions of my titles over the years.

In a capitalist society, progress too often means less attention is paid to issues of originality, craft, or the pride in making something beautiful. Mass production brings cost down and makes items more widely available, although most of what is saved goes into the pockets of industry, leaving the consumer with little remedy or protection. Much more dangerous, and less discussed, is the fact that when corporations control production they also create fabricated need—promoting public interest in that which benefits big business. Getting a population to buy what will make it less able to think for itself, more dependent on what the corporate bosses need, is an important part of the picture.

So perhaps my attachment to the book is a last gasp act of defiance, reminiscent of a different time, one in which independent thinkers could more easily start a small press and publish texts that would never have made it past the gatekeepers at Random House or Simon & Schuster. A time when I could call my independent bookseller and ask her to order a title that caught my fancy, or browse among bookshelves stocked with the unexpected, rebellious or magical.

Yes, I think it is one woman’s small statement: memory honored and unleashed. It is not about rejecting progress or failing to keep up with the times. I do all right in those departments. It is my own personal monument to the integrity of the word on the page: vicarious experience free from consumerist coercion.

Responses to “Farewell to Books?”