Ever since Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel invented dynamite 150 years ago, people have been trying to make lemonade out of his lemons. The most famous example is Nobel himself, who created the Nobel Prizes, rewarding peacemaking and sundry civilized achievements in literature and science, to atone for the murderous violence he unleashed on the world.

When Nobel’s brother died, a French newspaper mistakenly published an obit of Nobel himself, calling him a “merchant of death” and saying he “became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before." Reading his premature obit and wishing for a more benevolent memorial, Nobel set aside most of his estate to finance the Nobel Prizes.

The effort to find useful, even pleasant employment for explosives continues today in New Mexico, home of the biggest explosive of them all, the atomic bomb.

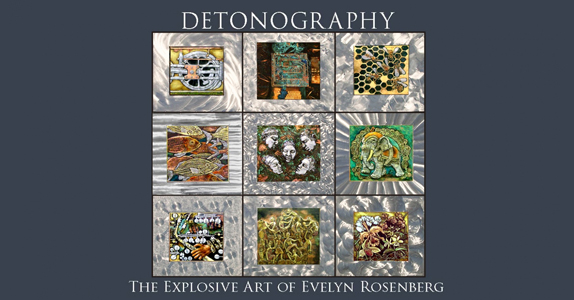

A new book published by the University of New Mexico Press, Detonography: The Explosive Art of Evelyn Rosenberg, parses and celebrates this current effort.

Written by Rosenberg (her daughter Mica Rosenberg is described in the acknowledgments as co-author), the book is skillfully photographed by John Trotter, a lifelong photographer, a semi-retired senior administrator at the UNM Medical School and until recently an East Mountain resident.

Written by Rosenberg (her daughter Mica Rosenberg is described in the acknowledgments as co-author), the book is skillfully photographed by John Trotter, a lifelong photographer, a semi-retired senior administrator at the UNM Medical School and until recently an East Mountain resident.

Rosenberg is an Albuquerque painter, printmaker and sculptor especially known for her large public works. What she and Trotter depict is a new way to create art using explosives. She invented the term “detonography” to describe her unique combination of art and explosives, converting destruction into beauty.

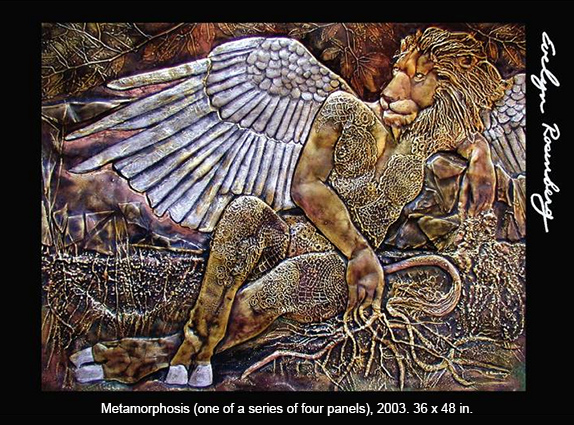

What she discovered was that plastic explosives could deeply etch objects onto metal plates, creating beautiful art. It was, she observed, “like strange, chiseled jewels—a leaf etched into an aluminum plate, its delicate veins elegantly raised on the surface, or a pretzel perfectly frozen in steel—exquisite detail formed by an explosion large enough to blow up a car.”

She quotes from the Kabala a statement with strong echoes in her own work: “The forces of creation, destruction and preservation have a whirling, dynamic interaction.”

Rosenberg developed her technique more than two decades ago with the help of a visiting Israeli military scientist, Gideon Sivan, who came to the United States to research civilian uses for explosives at the Energetic Materials Research and Testing Center near Socorro, which also happens to be just north of the Trinity Site where the first atom bomb was tested.

As an example of her process, the creation of a large piece called “Land of Enchantment,” which depicts the interaction of a series of people and animals, is documented in detail using both words and photographs.

Saying her fundamental interest is in “the relationship of humans to the natural world,” she explains the piece:

The idea of ‘Enchanted New Mexico’ reflects my relationship to the natural beauty of the state. Every day when I look out my windows I see the Sandia Mountains, and every day they are different. No matter how frustrated or unhappy I feel, when I look at those magical mountains I am comforted and refreshed. These mountains are full of the ancient spirit of the land, which I represent as both human and animal and which, I believe, are felt by all who love the mountains.”

Explaining why she wrote this book, Rosenberg says, “I have spent almost twenty-five years of my life perfecting this process and I don’t want all of my experience and information to be lost. It is not the easiest technique to access—high explosives are kept under twenty-four hour guard and can be used only by licensed technicians at a professional facility—but I hope one day other artists will be able to use Detonography, expand on it, change it, make it new. That is my motivation for writing this book.

While the technique Rosenberg has invented is unique, the impulse that brought her to it is as old as the Ramayana and the Iliad, as old as civilization itself: the desire to transmute the brutality, bloodshed and bellicosity of our machinery of destruction into something beautiful and uplifting, into art. That impulse did not begin with Alfred Nobel’s feelings of shame and guilt, and it won’t end with Detonography’s mysteries.

Responses to “Explosive art: something new under the sun”