Through the centuries, water was what brought diverse peoples to the imposing varicolored sandstone promontory that rises like a monolith in the northwestern part of New Mexico. The nearby Zuni Indians call it A’ts’ina, or Place of Writings on the Rock, though native peoples in the area must have had another name for it before the writing appeared. Spanish explorers called it El Morro, The Headland. Anglo-Americans call it Inscription Rock, honoring both the indigenous petroglyphs of human figures, animals, birds and geometric designs, and the later names and messages left by travelers passing through. The US National Park Service has named it El Morro National Monument, and it is one of the most fascinating yet least visited attractions in the state.

(Runoff and water tank. Images by Margaret Randall.)

Water, of course, was everything to native inhabitants, settlers, and those stopping briefly on their way somewhere else. One can imagine explorers coming up from Mexico on horseback and wagon trains of people pushing west, opening new country and relieved to discover the precious liquid after days of travel across unremitting desert and high elevation forest. Down the vertical wall of the imposing mesa, rains enter a pour-over and fill a reliable tank at its base. News of this tank must have spread in every direction. Although not by any means the only point of interest at El Morro, this tank is the focal point around which most of the inscriptions can be viewed.

El Morro is a rewarding two-and-a-half-hour day trip from Albuquerque. You drive west on I-40, then turn south on State Highway #53 between Grants and Ramah. You’ve passed imposing Mount Taylor and can glimpse the volcanic bed of the Malpaís as you enter the lovely Zuni Mountain country. The US government established Zuni National Forest in 1909, by appropriating land from the Zuni, Navajo, and Acoma reservations. All three tribes had settled this area. In 1912, the same year New Mexico attained statehood, the Zuni people were able to reclaim their land. They gained additional holdings in 1935.

Fifty or sixty years ago, a visitor to this area would have seen the ravages of logging and over-grazing, but successful protest managed to stop both in 1940. The Zuni Mountains receive an average of 24 inches of rain a year, twice that of the surrounding countryside. Ponderosa Pine alternates with Piñon, Juniper, Gambel’s and Gray Oak, and Mountain Mahogany.

Open spaces sport Sage and Rabbit Brush. Cranes, wild turkeys, eagles, hawks, coyotes, jackrabbits, squirrels, chipmunks, and several variety of snakes—including rattlers—can be seen. The area is lush and calming, but nothing quite prepares the first-time visitor for her initial sight of El Morro as it rises around a bend in the road. Unlike any land feature within miles, the massive rock is is unique and imposing.

Some of the surroundings here are volcanic, including El Malpaís National Monument on the other side of the Continental Divide. Others are simply grassy plains, sweeping to a horizon of distant mountains. The rock itself is conspicuous and inviting. You know you have arrived, but cannot know the mysteries in store: each natural feature or human-carved name and date suggests a history only partially imagined. You will need more than one visit to formulate, much less find answers to, the questions posed.

The approach to the national monument takes you through a small but well-appointed visitors center, out its back door and down a paved path, to the base of the monument. Here a half-mile trail to the right borders the rock, allowing for close inspection of the multicolored face itself, the water tank with its bull rushes and tall grasses, and the fascinating display of inscriptions.

Two thousand of these attest to more than a thousand years of human history. There are petroglyphs carved by Ancestral Puebloans that many years ago. Spanish and Mexican conquerors left their marks from 1605 to around 1800. Early settlers added theirs more recently. Each of these periods produced a record that has something interesting to tell us.

(Petroglyphs)

Some of the inscriptions are deeply incised and clearly legible. Others have faded over time. The notorious Don Juan de Oñate left his mark in 1605, and it is believed to be the oldest on the rock. I’m not sure who traced over his message and signature with some sort of dark ink, and I don’t know whether to bemoan the addition or be grateful that it makes it so much easier to read (it is the only message to have been so defaced). In its lines, Oñate recorded his success at having reached “the southern sea.”

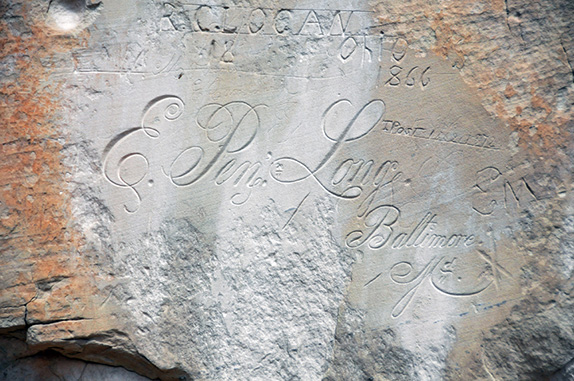

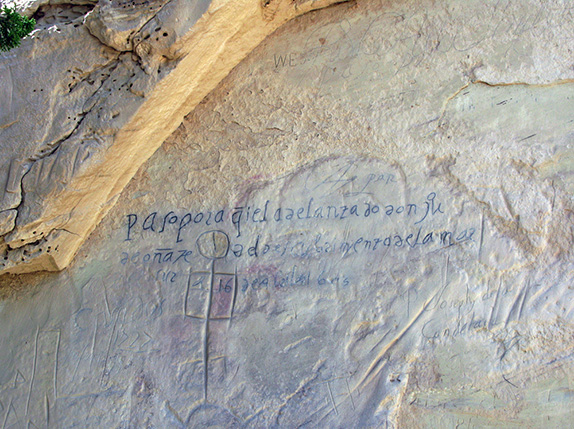

(Elaborate European penmanship)

(Elaborate European penmanship)

(The Oñate inscription has been inked in for legibility)

(The Oñate inscription has been inked in for legibility)

Oñate, hungry for riches and a title, was actually from Mexico. He traveled north, not at the request of the Spanish king but in hopes of bettering his own situation. He was responsible for the 1598 and ‘99 travesties committed against the people of nearby Acoma Pueblo. Faced with brave resistance, which included the Acoma people throwing some of the invaders off their 300-foot mesa, he ordered the right feet cut from a couple dozen braves and kidnapped a number of young women, taking them back to Mexico City as slaves. Back in Mexico himself, he was tried for his excessive abuses—deplored by the power elite even in the context of acceptable conquest that characterized the era. Oñate’s titles were stripped from him, and he served prison time for his crimes.

Some in the Southwest today insist on honoring Oñate with statuary, while many of us consider him to represent the worst of the Spanish Conquest. The inscription that recalls his passage here was written five years after his crimes at Acoma, and six after he established the first Spanish colony in what is now New Mexico. It seems hastily scrawled, almost childlike with its lack of capital letters and ragged configuration of letters. Perhaps it was carved by one of the invader’s underlings.

Many other expeditions left their mark on Inscription Rock. The earliest evidence of a group resting at its base is March 1583. Francisco Manuel de Silva Nieto passed through in 1629. And wagon trains representing many different prongs of the westward thrust spent a night or two at the waterhole. Lengthy messages continued to be incised in the sandstone as late as 1774.

The next decades, into the early 19th century, were a time of political and cultural contention for what would later become our state. As this part of Mexico was taken over by the United States, and became a US territory, it played a major role in westward expansion. Military expeditions were sent to explore the new territory. In September 1849 an Army lieutenant and topographical engineer named J.H. Simpson, and an artist named R. H. Kern, made their camp at El Morro. The artist spent two days copying the petroglyphs and Spanish messages, giving us the first scholarly record of their existence. These men also recorded their own visit, and were the first to leave an inscription in English.

(Was this W left by Richard Wetherill?)

(Was this W left by Richard Wetherill?)

To me, some of the most interesting carvings were made more than a hundred years later. One large W, for example, closely resembles the W with which Richard Wetherill made his mark at some of the Ancestral Puebloan ruins where he was the first non-Indian at the site. I have many times returned to stand before the W at El Morro, sometimes with photographs of Wetherill’s known signature in hand, trying to determine if he was really here sometime in the late 19th or early 20th century.

No less fascinating than the European script left by travelers from far afield are the petroglyphs left by people long before. People of whom we know little or nothing were the first to make use of the waterhole hidden at El Morro’s base and establish a base nearby. After the Colorado Plateau was abandoned at the end of the 13th century, Ancestral Puebloans moved into this valley. Around 1375 they began to build two villages on top of the rock, perhaps attracted to the site for its defensive qualities. A’ts’ina was once home to some 1,500 occupants. By 1400 they were gone.

(Ruins of A’ts’ina Pueblo on top of El Morro)

(Ruins of A’ts’ina Pueblo on top of El Morro)

Today low room blocs and a couple of kivas remain, providing a point of interest for those visitors to the monument who aren’t satisfied with simply examining the inscriptions at its base but complete the two-mile trail that switchbacks to the top and then makes its way across some beautiful terrain before looping back down to ground level once again behind the visitors center.

This mesa-top walk is what I like best at El Morro. First of all, it’s an easy hike, one almost anyone can do. I brought my mother when she was in her early eighties, and have visited with grandchildren younger than seven. Secondly, in an astonishingly brief distance, you traverse some pretty dramatic terrain. Once you top off at the end of the gentle switchback trail, you’re walking on slickrock. Occasional rock piles, or cairns, point the way.

To your right you are suddenly looking down into an intimate box canyon that surprises you by its location inside the massive rock itself. The color of the sandstone ranges from creams and oranges and pinks to a brilliant lavender-purple. If it’s recently rained, pockets of slickrock may be filled with pools of water, forming mirrors that reflect sky and clouds.

(Intimate box canyon within El Morro)

(Intimate box canyon within El Morro)

This mesa-top trail includes several narrow staircases literally carved into the rock. For some reason, probably having to do with how the land formation traps air currents, it is not unusual for you to find yourself with a menacing thunderstorm on top of El Morro. If it’s really bad, a ranger will run up and warn people to descend immediately. If it is simply a pileup of roiling clouds, though, it can add to the excitement. I’ve made some of my most evocative southwestern images of dark clouds reaching into the sky above the magical terrain of El Morro.

(As you hike the top of El Morro, you climb staircases cut into the rock)

(As you hike the top of El Morro, you climb staircases cut into the rock)

(Pools of water reflect the sky)

At the far end of the trail, just before you begin the descent, you reach what’s left of the ruins. It’s worth spending a bit of time exploring them. And don’t forget to stop a moment and look out at the broad vista below. I always try to imagine what the people who made their home here thought of the place they had chosen, as well as of the surrounding country. It is truly a place of beauty they must have hated to leave.

El Morro is a place where many different strands of living, exploration, conquest, and the need we humans have to leave our mark, are brought together by the existence and sustainability of water. History is written on the water and on the rock. This place is a reminder of the fact that without water nothing is possible: neither life nor art nor the messages each generation leaves to the next.

Responses to “El Morro: Crossroads of Cultures”