A young woman, a student at the University of New Mexico, gets into a BMW with three men, including two UNM athletes.

Later she shows up at her dormitory in tears and reports that she has been raped. Her lawyer says she was drugged.

The men say she had sex voluntarily with them. She says she blanked out because she was drugged. The investigation has been dropped at least temporarily. The students are still enrolled at UNM but she has left the school. Any prosecutions or even university disciplinary action, while theoretically possible, looks increasingly unlikely.

This incident, which transpired in April, and the questions it raises are typical of many of the sexual encounters on campuses around the country. Was it a sexual assault? Was it rape? What should the university, the police and the district attorney do about it?

Throughout the summer a committee of UNM officials, students, health workers and law enforcement officers is meeting at UNM to try to deal with a problem that in the past UNM, like most other campuses, has done its best to ignore.

For obvious reasons, colleges don’t want to draw attention to campus sexual assaults. Publicity discourages enrollments, makes fund raising more difficult, antagonizes alumni, jeopardizes legislative and congressional appropriations, and blackens a school’s reputation. Colleges do not have the power to bring criminal charges or imprison culprits, and without subpoena power or other means to compel testimony and protect witnesses, they do not have the ability to investigate charges thoroughly. Nor do even the best intentioned college administrators have any desire to get into the business of investigating and prosecuting crimes.

There remain however, two areas in which colleges have the ability and the legal obligation to act. One is preventing sexual aggression and the other is helping students cope with its aftermath when it occurs. Colleges have not done either job very well, as many, including the University of New Mexico, are now admitting.

Figuring out the size of the problem is a problem in itself. There have been two major federal studies by the Department of Justice, in 2000 and 2007. Both were seriously flawed. The most recent federal study in 2010 was based almost entirely on data from the earlier studies. The 2000 study was a random sample of college women. During phone interviews they were asked if they had been raped during the six months of the current academic year; 2.8 percent said they had experienced rape or attempted rape in those six months, and 15.7 percent said they had been sexually assaulted. That six-month data were then multiplied to supply an estimate of the frequency of rape during a typical student’s four-year college career. The conclusion was that 20-25 percent of students would be raped wile at college. The report also concluded that on a campus with 10,000 female students, 350 would be raped each year.

The 2007 study, based on a web-based survey of a little over 4,000 students at two state universities, one in the South and the other in the Midwest, came up with a figure of 20 percent of coeds raped.

Both studies have serious problems. Fewer than 50 percent of those solicited agreed to participate. The definition of rape and the distinctions between rape and other types of sexual assault and harassment were blurred. Incidents that the women themselves might not describe as rape were so categorized if alcohol or drugs were involved.

The figures are so horrendous that they almost stagger the imagination. They have been spotlighted in both a White House report titled “Not Alone,” presented by Vice president Biden in April, and a speech by President Obama. They are still the basis of almost all journalistic reports on campus violence. Recently, the Albuquerque Journal relied on the 20 percent figure in a news story, although the newspaper did not give the source for the figure.

Most of those attacking the college rape studies have been conservatives, including columnist George Will and the American Enterprise Institute, as well as a few women famed for their anti-feminist ideology. Questioning the data puts me in some company that I don’t relish, but it has always been the job of a journalist to follow the facts wherever they lead. And the facts do not support the often-repeated statement that 20 percent of college women are raped.

At UNM, between 2009 and 2012 there were 14 reported rapes. Some national estimates suggest that only 20 percent of rapes are reported. The 2000 study said 5 percent of campus assaults were reported. This would suggest that UNM may have had between 70 and 280 rapes over the four years—an enormous figure but nowhere near the 350 a year or the 2,000 over four years that the studies suggest.

But doesn’t it matter less how many college girls are raped than that rape is a constant and ubiquitous threat? A web site for UNM coeds to discuss sexual predation is replete with nightmarish stories of unwanted sexual advances, some culminating in rape with lasting physical and psychic injury, others merely embarrassing and frightening.

In commenting on the April incident, one UNM official dismissively said rape happens on all campuses; the subtext was that young women should just grin and bear it.

But in recent months UNM may have learned something from the controversy. UNM Dean of Students Tomás Aguirre was quoted recently in the Journal, “If it was only one report of sexual violence a year, that would still justify the effort [at prevention] in my mind. “I feel as dean of students, every student should have the safest experience possible.”

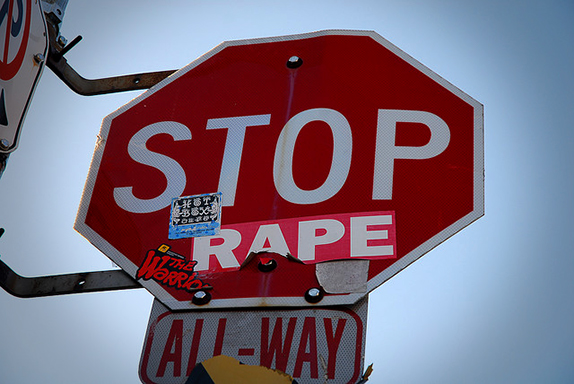

(Photo by Nigsby)

Responses to “Does it matter how many students are raped?”