Having grown up in Orlando, Florida, I had the sort of close relationship with Disney that allows the perfectly executed fantasy to be slowly chipped away. The Victorian houses on Main Street, USA, reveal themselves as empty, one-sided plaster. The waving characters of your childhood eventually become your fellow college students, sweating off last night’s binge drinking under a costume in Florida’s 100% humidity. The happy families are desperate, like ours, to make the Disney experience worth the savings and idealism spent on it. This is to say nothing of the commercialism and less-than-spit-spot image of the Disney family and corporation. In Orlando, Disney controversies are well known in the way cities gossip about their local celebrities: one part rueful shame, one part agreement to uphold the image that keeps tourist dollars coming for an all-inclusive stay.

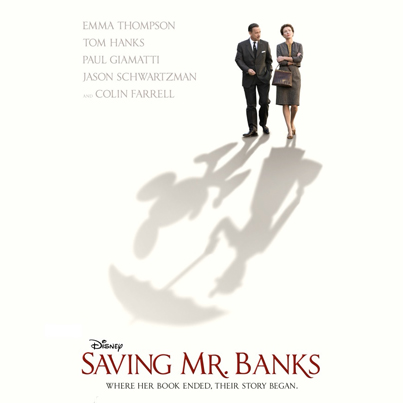

I brought this set of experiences with me to the preview of Saving Mr. Banks, where I anticipated the core elements I expect from any Disney-produced Disney-self-reflection: a flair for recreating a time and place through rose-colored glasses, copious references to Disney franchise material, and the occasional stab at a sterilized emotional climax. Saving Mr. Banks—a recreation of Walt’s quest to secure the rights to Mary Poppins from author P.L. Travers—delivered all those elements. Had this been any other story, I would have been as satisfied as the average adult raised steps from Cinderella’s castle, where hometown values include an overdeveloped proclivity for suspension of disbelief.

Saving Mr. Banks, however, sets its thematic sights too high to be allowed any praise for the usual Disney application of fairy dust and forced revelatory moments. The film tries to dissect the relationship between the pain of childhood and its power to act as catalyst for children to either outgrow the world of fantasy or cling to it all the more dearly. It attempts to give us a meaningful, human connection to Walt and the Disney franchise, telling us there is a benevolent morality behind creating the happiest place on Earth, the happiest films on Earth, and the happiest market on Earth.

In the film, the dark side of make-believe is developed through yellow-filtered flashbacks of Travers’ childhood, awakened in her in the present day (1960s) by the adaptation of her Mary Poppins books. The flashbacks of her wonderfully imaginative but hopelessly alcoholic father are stretched out over the length of the film until you can feel their seams ripping and their stuffing falling out like so many plush Mickey Mouses. The central problem in the film’s execution is this epic overture aimed at proving it is a serious, self-aware portrait of the meaning of the Disney myth—comforting pain with fantasy—only to be followed by a stream of patented, tidy heartstring-pulling moments. Walt reveals his dark childhood memories, which amount to a trifle to anyone who has, say, watched an hour of local news or read the history of any era. His story of working hard as a paper boy and receiving a whipping from his father are given a big-eyed Tom Hanks monologue in which the predominant feeling is 'this is a Tom Hanks monologue'. The scene feels as if it could have been cut from a number of other films and dropped into Saving Mr. Banks the way Disney animation recycles movements.

While the film disappoints when it comes to its most promising premise, there is another meta problem; a more important issue that is left out of most of the commentary on this odd bit of Disney imagineering: the fact that, after P.L. Travers was so distraught to have her beloved fictional characters portrayed in Disney fashion and after fighting over her rights to her own story, Disney & Co. turned the author’s entire life into the very twittering, sing-songy musical, stripped of all its more complex elements, that she so despised. In the film, one feels that Walt Disney would go to any lengths to procure from Travers the rights to his own version of Mary Poppins; now it feels that, as an added measure of showing Travers who holds the reins, Disney made her life in the image of their fantasy as well. Disney struck P.L. Travers with the ultimate post-mortem gotcha.

Let’s take a few basic, foundational elements of the film. Travers’ father’s alcoholism is vaguely portrayed as leading to his death, with the intersection of the major storylines and darkness-cum-fantasy themes climaxing on this point; in reality, he died, admittedly anticlimactically, of influenza. P.L. Travers is portrayed as leaving the Disney experience mostly satisfied and rejuvenated; in reality, she felt disrespected and mistreated by Disney and the film team for the rest of her life, even making arrangements in her will to exclude them from further adaptations of her work. She is portrayed as a stuffy, lonely, and plain British woman; in reality, she was bisexual, studied Zen Buddhism in Japan, and adopted a son chosen by her astrologer. In short, a woman who did not want her fictional characters Disney-fied ended up with her entire life put through Disney’s revisionist process for Disney’s own glory.

Like Tom Hanks’ portrayal of Disney, the portrayal of P. L. Travers is only okay if “Saving Mr. Banks” is the first and last thing you ever know about the real people. In the end, this is likely exactly what Disney & Co is counting on. Like the droves of visitors who don’t want to knock on the hollow facades of the Magic Kingdom, the projected profits and Oscar predictions for Saving Mr. Banks hint that Disney knew its audience would be willing to overlook reality for another chance to believe in the Disney fantasy.

Responses to “Disney’s Façade in Saving Mr. Banks”