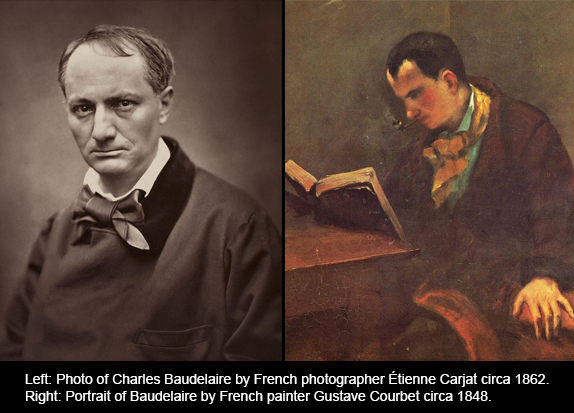

“The Sage laughs not except in fear and trembling.” It was with this dark maxim that Charles Baudelaire began his essay “On the Essence of Laughter,” the introduction to a discussion of the art of caricature that was serialized in one of the many alternative Parisian newspapers in 1857, the same year that he published “The Flowers of Evil.” He couldn’t remember exactly where he’d come across that snippet of wisdom, whether it was from the Biblical Solomon or some latter-day French source, where it had surely been only a quotation.

“But come,” Baudelaire continues, “let us analyze this curious proposition. The Sage, that is to say he who is quickened with the spirit of Our Lord, he who has the divine formulary at his finger tips, does not abandon himself to laughter save in fear and trembling. The Sage trembles at the thought of having laughed; the Sage fears laughter, just as he fears the lustful shows of this world. He stops short on the brink of laughter, as on the brink of temptation. There is, then, according to the Sage, a certain secret contradiction between his special nature as Sage and the primordial nature of laughter.”

The recent killing of cartoonists and the editor at the satirical journal Charlie Hebdo in Paris by Islamic extremists, who took offense at its gross caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed, shocked the world. It led to a massive demonstration in the city on January 11, a march of solidarity on behalf of freedom of expression and condemning acts of terrorism. With an impressive number of world leaders at its head, it was attended by more than three million participants.

But there was also widespread negative reaction throughout the Muslim world, where both the nature of the cartoons and the perceived geopolitical implications of the march in the European capital were rigorously denounced. To all of this, Baudelaire’s musings might provide some unexpected insight.

“Laughter is Satanic”: Laughter and the Fall

Although he says he has no wish “to embark recklessly upon a theological ocean,” Baudelaire has nevertheless laid a finger on a central issue for those followers of the Prophet with their guns, and for their sympathizers.

“If you are prepared, then, to take the point of view of the orthodox mind, it is certain that human laughter is intimately linked with the accident of an ancient Fall, of a debasement both physical and moral.” Laughter and grief, Baudelaire points out, “are both equally the children of woe,” progeny of the human knowledge of good and evil.

“In the earthly paradise—whether one supposes it as past or to come, a memory or a prophecy, in the sense of the theologians or of the socialists—in the earthly paradise, that is to say, in the surroundings in which it seemed to man that all created things were good, joy did not find its dwelling in laughter. As no trouble afflicted him, man’s countenance was simple and smooth, and the laughter which now shakes the nations never distorted the features of his face.”

It goes without saying that the goal of fundamentalism is to get back to the mythical garden—to get out of the troubles that have befallen us since. However, if the “Sage” so-described begins to sound like the stereotype of some grimly humorless Muslim imam, Baudelaire points to the “officially Christian character of the maxim”—that Jesus, “the Sage par excellence, the Word Incarnate, never laughed. In the eyes of the One who has all knowledge and all power, the comic does not exist. And yet the Word Incarnate knew anger; He even knew tears.”

“But first of all we ought to make a proper distinction between laughter and joy,” the poet argues. “Joy is a unity. Laughter is the expression of a double, or contradictory, feeling; and that is the reason why a convulsion occurs.”

He then gets down to the nitty-gritty. When it comes to laughter, you can’t help yourself: “I said that laughter contained a symptom of failing; and, in fact, what more striking token of debility could you demand than a nervous convulsion, an involuntary spasm comparable to a sneeze and prompted by the sight of someone else’s misfortune? … To take one of the most commonplace examples in life, what is there so delightful in the sight of a man falling on the ice in the street [or slipping on a banana peel?] … that the countenance of his brother in Christ should contract in such an intemperate manner, and the muscles of his face should suddenly leap into life like a clockwork toy?”

And what are we to make of this automatic reaction? “If you care to explore this situation,” Baudelaire continues, “you will find a certain unconscious pride at the core of the laugher’s thought. That is the point of departure. ‘Look at me! I am not falling,’ he seems to say, ‘I would never be so silly as to fail to see ice on the pavement.’” This ungenerous reaction is, according to Baudelaire, the “primordial law of laughter.” We cover the shock of witnessing an instance of the universal affliction of human vulnerability with a sense of superiority, of pride in having been personally spared humiliation and disgrace.

“Laughter is Satanic: it is thus profoundly human. It is the consequence in man of the idea of his own superiority. And since laughter is essentially human, it is, in fact, essentially contradictory; that is to say that it is at once a token of an infinite grandeur and an infinite misery—the latter in relation to the absolute Being of whom man has only an inkling, the former in relation to the beasts. It is from the perpetual collision of these two infinites that laughter is struck.”

Could it be that the attackers were reacting as much to the arrogance of the mockers’ implied superiority? Is that not also why the American towers of commerce were brought down on 9/11? Wasn’t it resentment over the arrogance of American power and the tyranny of the Western dominance of world trade that were attacked?

Using the language of his time, Baudelaire takes an ironic view of his own century’s sense of privilege in these matters: “Comparing mankind with man, as we have a right to do, we see that primitive nations … have no conception of caricature and have no comedy (Holy Books never laugh, to whatever nations they may belong), but that as they advance little by little in the direction of the cloudy peaks of the intellect, or as they pore over the gloomy braziers of metaphysics, the nations of the world begin to laugh diabolically…. As the comic is a sign of superiority, or of a belief in one’s own superiority, it is natural to hold that, before they can achieve the absolute purification promised by certain mystical prophets, the nations of the world will see a multiplication of comic themes in proportion as their superiority increases. But the comic changes its nature, too. In this way the angelic and the diabolic elements function in parallel. As humanity uplifts itself, it wins for evil, and for the understanding of evil, a power proportionate to that which it has won for good.”

As early as the fifth century BCE, Herodotus wrote similarly of cultures he encountered in his travels, “Men whose laughter deserves report are marked,” he wrote, “because laughter connotes scornful disdain, disdainful feelings of superiority, and this feeling and the actions which stem from it attract the wrath of the gods.”And in the Republic, Plato says that the guardians of the state should avoid laughter, “for ordinarily when one abandons oneself to violent laughter, his condition provokes a violent reaction,” and he argued that tight controls should be in place to protect the state.

In the character of Melmoth (Melmoth the Wanderer, 1820, by the Rev. C.R. Maturin) Baudelaire has struck upon a parallel to the Charlie Hebdo humorists, who find themselves trapped in a society gone wrong and who pride themselves on making hamburger of all its sacred cows: “… [His] laughter is the perpetual explosion of his rage and his suffering. It is, you must understand, the necessary result of his contradictory double nature…. It is a laugh … which is the highest expression of pride, and is forever performing its function as it lacerates and scorches the lips of the laugher for whose sins there can be no remission.”

The Licensed Fool

“I killed them!” the comedian gloats backstage after a successful performance. Most of us don’t die laughing. But laughter is also known as a great equalizer—like death. Like death, it reduces us all and confronts us with the same sense of universal helplessness that underlies the human condition.

Most of the world’s societies have made a place for the “fool,” the “clown,” or the “trickster”—those recognized as outside the norm, whose presence provides a different slant on things by being somehow “out of kilter.” Recognized as deviating from the norm only “by the grace of God,” however, they were thus kept at court as comparative reminders of the precariousness of normalcy.

In the European royal courts, a distinction was made between the “natural” fool and the artificial or “licensed” fool. “Natural” fools were those “touched by God”—individuals compromised by physical or mental developmental disorders or deformities (dwarfs and humpbacks, those afflicted with Down’s syndrome, mild schizophrenia, or learning disabilities, which led them to be called idiots, lunatics, nit-wits, ninnies, nincompoops). The category of “natural” fools also included ignorant or “clueless” country people—hayseeds, country bumpkins, or clods (the original meaning of “clown”), or rubes (from Rubin/Reuben, which originally meant something similar to “red-neck,” exposed to sun and wind)—who were looked upon as mentally challenged and inferior figures of fun. People you could feel superior to.

Yet, ultimately, the tolerance of the fool at the European courts had to do with the fallibility of all flesh, and it drew its justification from the Bible and the words of the Apostle Paul (I Corinthians, I:27 – 29):

“But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty; And base things of the world, and things which are despised, hath God chosen; yea, and things which are not, to bring to naught things that are: That no flesh should glory [itself] in his presence.”

While there may have been a charitable motive for bringing “natural” fools to court, the “licensed” fool was specifically brought in for entertainment value, and for the wit and wisdom of the off-kilter. “The [‘licensed’] fool’s status was one of privilege within a royal or noble household. His folly could be regarded as the raving of a madman but was often deemed to be divinely inspired.” (The Royal Shakespeare Company, “Notes on the Fool.”) He was given leave (license) to play the fool, dressing up in the disordered motley of the mentally handicapped and imitating their antics and speech. In the role of the fool, he could say things that others could not, challenging the prevailing normalcy, reducing all hierarchies, and showing up the absurdities of the society’s foibles, hobbyhorses, and sacred cows.

The Charlie Hebdo artists brought the critical posture of the “licensed” fool to their work, satirizing their targeted subjects in order to promote change and bring down the tyranny of received ideas. Their ridicule involved applying the distorted characteristics of the “natural” fool to their hapless victims, drawing their bodies with the proportions and deformities of the dwarf, giving them the bulging and rolling eyes of the deranged madman, the bulbous nose of the sot, and the antic behavior of the witlessly obsessed.

Nevertheless, as a young Tunisian living in Paris told a BBC interviewer in the aftermath of the attacks: “Make fun of yourselves if you will, but leave others alone. The media is like a car: you need a license to be on the road; otherwise you will be a danger to others. Charlie had no license to put people’s lives at risk with their provocations.”

Back in February 2006, Charlie Hebdo published cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad that had appeared in Danish newspapers and which had caused a worldwide uproar. In the March 1 issue they followed up with the publication of a letter signed by 12 noted writers, mostly Islamic, but including Salman Rushdie and Bernard-Henri Levy, defending freedom of expression and speaking out against what they called “Islamism,” a strain of totalitarian extremism that seemed to be overtaking Muslim communities throughout the world:

We, writers, journalists, intellectuals, call for resistance to religious totalitarianism and for the promotion of freedom, equal opportunity and secular values for all.

Recent events, prompted by the publication of drawings of Muhammad in European newspapers, have revealed the necessity of the struggle for these universal values.

This struggle will not be won by arms, but in the ideological field.

It is not a clash of civilizations nor an antagonism between West and East that we are witnessing, but a global struggle that confronts democrats and theocrats.

Like all totalitarian ideologies, Islamism is nurtured by fear and frustration.

Preachers of hatred play on these feelings to build the forces with which they can impose a world where liberty is crushed and inequality reigns.

But we say this, loud and clear: nothing, not even despair, justifies choosing darkness, totalitarianism and hatred.

The cover of that issue carried the caption: “If Mohammad Returned.” The cartoon under it depicted the Prophet bound and on his knees with a black-clad jihadist standing behind him in the process of beheading him. “I am the Prophet, stupid!” protests the bound man, while the ski-masked jihadist slits his throat. “Shut your mouth, Infidel!” snarls the jihadist.

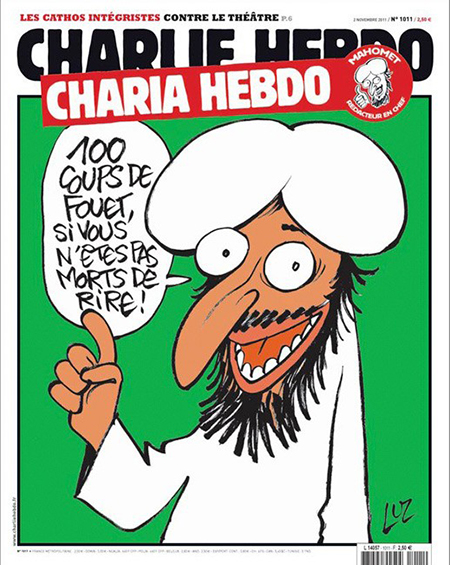

In November 2011 the newspaper’s offices were fire-bombed. They had just printed an issue called “Charia Hebdo” (punning on “Sharia”), listing the Prophet Mohammad as “guest editor” and featuring a caricature of Muslim imam (who might be interpreted as the Prophet) on the cover. “100 lashes if you are not dying of laughter,” the figure admonished. After the fire-bombing, the paper’s cover carried a drawing of a Muslim-garbed figure and a Charlie cartoonist “French kissing” in an embrace, with the words overhead declaring: “Love: Stronger than Hate.”

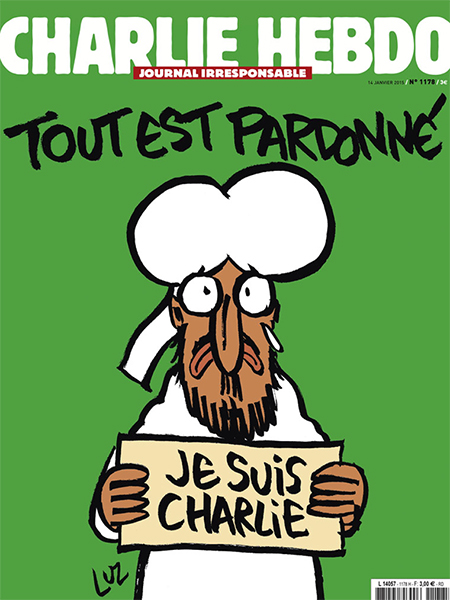

That cover was, in its way, as ambiguous as the cover released by the surviving Charlie Hebdo staff after the January 7 massacre. Appearing after the massive march of solidarity in Paris on January 11, it featured a tearful and distressed-looking Muslim (Mohammad?) holding a “Je suis Charlie” sign. Bold lettering at the top read, “All is forgiven.” Was it truly a gesture of reconciliation? The irony at the center of all of Charlie’s cartooning gives the supposed sentiment a wry twist, suggesting that the Muslim community was equally victimized by the terrorist attack. But, in both covers, the language used declares a commonplace Christian ideal, couching it in the form of a cliché. Are they satirizing the overflow of pompous rhetoric and self-flattering idealism that surrounded the public’s reaction to the events?

It’s hard to know, one way or the other. But it is to be hoped that, if Charlie survives, it will continue to provoke with the same kind of pungent challenge to our assumptions and presumptions, our arrogant conviction in our ability to understand and to stake a claim to the moral high ground.

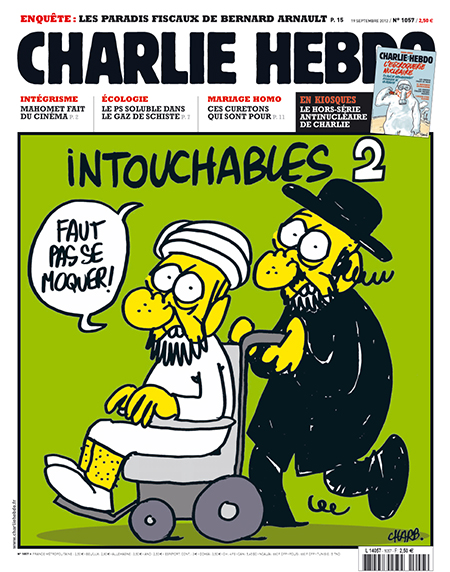

In September 2012 Charlie responded to the public furor over the controversial film The Innocence of Muslims by showing a naked Mohammad posing for a skin-flick. Loudly denounced for going too far, they then created a cover in response to a film called The Untouchables, which featured an Orthodox Jew pushing a battered Muslim in a wheelchair. The caption above read: “You must not mock us.”

“The aim is to laugh,” stated Charlie staff member Laurent Leger at the time, “We want to laugh at the extremists—every extremist. They can be Muslim, Jewish, Catholic. Everyone can be religious, but extremist thoughts and acts we cannot accept.”

In the Muslim world, however, “Such images are seen not as criticism, but as bullying,” according to Hussein Rashid, professor of Islamic studies at Hofstra University. “Violence, as a response, is clearly wrong and disproportionate. However, it is not so much about religious anger, as it is about vengeance.”

The Politics of Resentment and the Bamiyan Buddhas

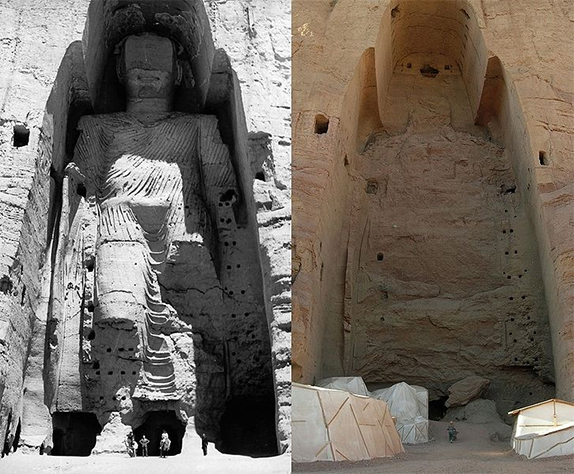

The attack on Charlie Hebdo was not the first time that the supposed prohibition of images had been co-opted by the politics of resentment and used as an alibi for provocation. In early 2001 the Taliban had ordered the destruction of two giant Buddha figures that had been cut into a mountainside in Afghanistan in the 6th century.

In Buddhist practice, contemplation of an image of the Buddha is merely an aid to meditation. The Buddha is not a god, and the image is not an idol to be worshipped. The great rock-cut Buddhas of Bamiyan were stupendous in size (175 and 120 feet tall) in order to give visual expression to the transcendent nature of the Buddha, which encompasses the entire universe and which was literalized in the figures’ scale. But they also expressed the central Buddhist principle of the transience of all things, even something so seemingly permanent as a mountain, and the mountain, like the figure embedded within it, was understood as an illusion.

The Bamiyan Buddha sculptures were part of a UNESCO World Heritage site. But the U.N. had imposed economic sanctions on Afghanistan for the Taliban regime’s harboring of Osama bin Laden, its support of international terrorism, and for its human rights abuses at home. The sanctions and the depredations of prolonged war with Russia, coupled with widespread crop failure, had led to conditions of extreme hardship, and Afghanistan was facing massive famine. Under these conditions, when a European delegation of preservationists met with the Taliban leaders, offering money to finance the sculptures’ upkeep and conservation, and when some Japanese proposed to actually remove the offensive sculptures by cutting them from the rock and taking them to Japan at enormous expense, the Taliban took the sculptures hostage. They demanded that the money be used for relief “to feed the starving children” instead. When that demand was refused, the hostages were, in effect, publicly executed.

A thing that the Taliban had intended to do in any case was thus transformed into a tremendous propaganda tool with maximum shock value, designed to emotionally intensify the political tensions on both sides of the divide between the Muslim world and the West. To the West, the Taliban were able to demonstrate their defiance of outside intervention. To the Muslim world, they were able to fuel an already mounting resentment, sending a message of solidarity in piety and belief, while exposing the West as callous interventionists who are more concerned with using their economic advantages for the protection of a blasphemous form of art than with the humanitarian interests of “starving children.” Nevertheless, the destruction of the Buddha sculptures took three weeks to accomplish, and at a cost in armaments, explosives, and man-hours that probably could have fed a dozen villages for a year.

Terrorism relies on the use of violent action that is guaranteed to produce an automatic gut reaction. Horror and disgust join a heightened sense of insecurity, the mortal fear that violent death can be meted out at any moment, and awareness that the social fabric is powerless to provide protection.

In one respect, both the extremist reaction and the Charlie cartoons are alike. They are both like graffiti, a gesture of social defiance and a defacing of the shared public façade. But, like graffiti, both are also a cry from the heart that gives public voice to the voiceless and a subversive power to the powerless. For those swept along by forces beyond their control or comprehension, graffiti provides a chance to leave an assertive trace of their passing—a defiant Bronx cheer or raised middle finger in angry valediction, a point-blank dismissal of the tyranny of this world and all it stands for.

The Prohibition of Images

But what lies behind Islam’s antipathy toward images? It can be traced back to Mohammad’s early struggle to establish belief in monotheism against paganism and the prevailing practices of idol worship. Mohammad’s revealed God was the God of Abraham, the Deus absconditus (Isaiah 45:15)—the God who hides himself, the unseen God who is the Creator of all things. Mohammad accepted the commandments that this God gave to Moses: that there should be no other god, and that no “graven images” should be made to be worshipped in his stead, nor should there be any other attempt to visualize his presence. As it was God’s prerogative as Creator to give form to all things, it was deemed blasphemy for anyone to form images of any living thing.

Images offer only substitutes for direct engagement with the world that Allah has created. Images distract from the truth of the real (whose essence is invisible, in any case). We would all do well to heed the Prophet’s admonishment and look at the world around us with renewed directness and respect. All of Creation is inimitable. It cannot be matched. It is futile, vain, and even sacrilegious to try. The world must be taken one on one.

In our time, however, images have gone viral and global. We freely revert to their substitutions, our experience of the world almost entirely mediated. With the proliferation of images through photography and cinema, publishing and television, and with the new digital media of the internet, iPads, and smart phones spreading rapidly throughout the world, Islam has been hard pressed to come to terms with the new state of affairs. Sometimes the clerics have argued that only handmade images are prohibited, and that photos are permitted because they merely capture the sight of things that God has already made. It has also been suggested that streaming and live video broadcasts are not unlawful, because they are not fixed and permanent. Videotape and digital photos, it is reasoned, merely arrange particles and data in such a way that the images only appear on screen when retrieved, like those stored in memory.

I was struck by a strange incongruity in a picture published by Reuters. A photographer who has been documenting the massive demonstration on January 12 at Grozny, the Chechnyan capital, is seen snapping a “selfie” with his phone. On a high balcony, he holds up his phone so that he will be seen against the mass of demonstrators who have come together to protest the January 11 gathering in Paris and to denounce the blasphemous Western attitude toward images, especially pictures of the Prophet. It was a touching image of our human frailty. I couldn’t help it; I had to laugh.

While the Qur’an only indicates that it is blasphemy to imitate the formative process of the Creator, in the collected sayings of the Prophet recorded in the Haddith, reference is made to a maker of pictures who is confronted on the Judgment Day. He is told to breathe life into his creations, and when he cannot do so he is consigned to Hell Fire.

But there’s another thunderous passage in the Hadith (according to the online IslamicAcademy.org), in which the Imam Tirmidhi reports that the Prophet said: “On the Day of Judgment, part of the Hell Fire will come forth with two eyes with which to see, two ears with which to hear, and a tongue with which to speak, saying, ‘I have been ordered to deal with three [offenders]: he who holds there is another god besides Allah; with every arrogant tyrant; and with every maker of pictures.’”

What about that second of the three sinners—the “arrogant tyrant”? Why hasn’t the sin of the bully tyrant received equal attention? If “those who will be most severely punished on the Day of Judgment will be those who try to imitate what God has created by making pictures,” isn’t it just as true that tyrants are to be punished for attempting to “play God,” to imitate and usurp the place of God by presuming to mete out God’s justice?

When Hell Fire comes breathing down, who’ll get the last laugh?

Responses to “Charlie Hebdo and Baudelaire’s Laughter”