Editor's note: Longtime New Mexico newsman and author Wally Gordon is on an extended stay in California where he's dispatching his adventures and observations.

California has a reputation of being the future incarnate, of being the place that gets there—wherever there is—before anywhere else does. It’s been true of everything from education to taxes to sexual relations to pot. (In 1996 California became the first to approve medical marijuana, followed by nearly half the states, including New Mexico).

If California is equally pathbreaking in the world of media, what lies in wait for us in New Mexico?

California launched the great media shrinkage earlier than New Mexico, and it has gone further and cut deeper. Once a stage for large vibrant newspapers in its huge metropolitan areas, these giants have stumbled into the land of Lilliput. The biggest of them all, the Los Angels Times, The San Diego Union-Tribune and the San Francisco Chronicle, are diminutive versions of their once massive and wealthy selves.

The largest and best paper north of San Francisco, the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, in a city of only 140,000, had more readers than the Albuquerque Journal with a readership area of 2 million. Once a proud member of the New York Times stable of papers, it went through three owners in 18 months and since 2007 has lost half its circulation, curtailed its news space, sharply reduced its local news coverage (the most expensive kind of reporting) and fired part of its staff.

If all that sounds familiar to readers of the Albuquerque Journal, it is not coincidental. The same trends have infected papers everywhere, although small town and rural papers have resisted the trend better than the others for reasons I will discuss below.

Even free newspapers have joined the rush to the bottom. Just as Albuquerque’s Weekly Alibi is a shrinking shadow of its former self, so are the numerous free weeklies of northern California. One venerable San Francico weekly was recently rescued by a local millionaire, who immediately fired the long-time editor, who is now trying to put together the area’s first real news website. Other freebies have disappeared entirely, shrunk their ambitions or sought other ways of surviving. One route is to become a “community newspaper” in which all the content is supplied by (unpaid) readers. Another fad is for “good news.” Translation: no news at all.

Just as in New Mexico, radio and TV stations, web sites and blogs have struggled, and failed, to fill the vacuum. My “Mountain Musing” column is published by the New Mexico Mercury, an honest and valiant effort by two long-time and well-known Albuquerque writers (V. B. Price and Benito Aragon) but it is still a long ways from being a news outlet that could replace a daily newspaper like the shuttered Albuquerque Tribune.

Why all this has happened to newspapers is fairly straight forward. The Internet captured nearly all of the classified ads and many of the display ads that used to finance 80 percent of newspaper operations. Even the remaining 20 percent paid by readers (subscribers and single-copy purchasers) shrank as more and more readers got their news from the web. As income disappeared, so did reporters, editors and news stories, giving readers fewer and fewer reasons to buy newspapers; and without readers, advertisers rushed even faster for the exits. Thus a malevolent cycle was set in motion that continues today.

What can be done about it is a bit more complicated than why it happened. Some have given up on journalism, but I have not; I believe journalism will find a way to survive because we need it.

Newspapers, especially the huge monopoly papers that dominated metropolitan areas until recently, are only one way of disseminating news. The web is cheaper and more effective for many reasons and could lead to a renaissance of journalism. It hasn’t done so, but it could. Here’s why.

On the web, newspapers have no printing cost and no delivery cost, and these two items account for much of a newspaper’s expenses. The web also has several great advantages over a printed paper.

First, it can be updated continuously, any time day or night that news occurs without waiting for predetermined deadlines and printing and delivery schedules.

Second, space is virtually infinite. For example, a photographer, who is an expensive member of the staff, is sent to cover a story and takes 200 pictures, of which 20 are great but only one can be printed. On the web, all 20 can be used.

Third, the content of a web site can be linked, archived and searched. When a story refers to a document, the entire document can be available through a link. When a new story updates an older one, readers can search out the older one for background. When a student or a businessman wants to research a topic for a school paper or a planned investment, he can search the archives.

But with all these advantages, web sites have failed to replace newspapers. Why? The experience of small rural papers like The Independent helps explain the reason.

Any web site, like any newspaper, has to be competitive in its content. This is relatively easy for a weekly newspaper in a rural area like Edgewood, where there are no local commercial radio or TV stations or daily newspapers, where city media like the Journal and the Santa Fe New Mexican as well as radio and TV stations essentially ignore those things that local residents are anxious to know about.

Thus the key to the continuing survival of a small town weekly is unique and useful news. Giving people information that they need and can get nowhere else is the magic key to the kingdom of success.

The same is true on the web. A successful web site needs to give people news unobtainable elsewhere, but almost no web site does that. Nearly all so-called “news” web sites merely republish information from print publications and other web sites or comment on information published elsewhere. Very, very few actually do their own reporting or generate any kind of original information. Very, very few have significant staffs of editors and reporters who are paid at professional levels to go out and find the news, write it, edit it, verify it and compile it into a comprehensible and valuable online report.

The problems for web sites are essentially two. One is that web sites attached to newspapers lack imagination on how to use this new platform. They are far too cautious about publishing extensive photo files, for example, or original documents or other ancillary information that could give unique depth and breadth to their coverage.

The other problem is that they lack the money to do a first-class job. Web ads simply don’t bring in anywhere near as much revenue as print ones. Classified ads, for example, have been substantially preempted by free sites such as Craigslist.

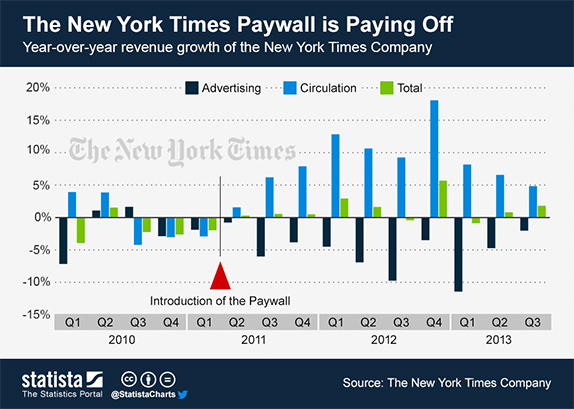

But if advertisers will no longer pay the freight, there is an alternative: readers. The New York Times, surprisingly for the newspaper that has long been known as the Old Gray Lady, has been leading the exploration of the new media world (perhaps grounds of hope for all old gray ladies of whatever gender or corporeality). The Times recently reported that for the first time ever—ever for the Times, ever for any major publication—it is getting more revenue from readers than from ads.

This is not because its print editions are growing, which they are not, but because it started charging for its online news and slowly over the past few years readers have come to accept these charges. And the reason they accept them is that they find in The Times information that is both unique and useful.

The idea of free online news, like the idea of free radio and TV, is an American tradition but a misnomer. Nothing is really free. You pay for “free” broadcast ads every time you buy a product, because the additional ad costs are built into the cost of the product. You also pay for it in the time you waste watching or listening to ads.

By the same token, you pay for “free” online news by getting a lot less of it, and what you do get is often second hand and unreliable.

So there is a way out of the journalistic mess created by the web, and that is by heeding the old maxim: If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

Just as much as anybody, maybe more than many in fact, I relish my unfettered access to free news from Politico and the Guardian and the Albuquerque Journal and a dozen other sources I regularly consult. But, alas, sooner or later my “free” ride is going to come to an end. The future of journalism, which really means the future of an informed public as the bedrock of democracy, depends on it.

Responses to “California and the Media Revolution”