Here in New Mexico we’ve had our share of star-gazing and imagined alien visitations. Roswell, most famously, has made a small industry out of events that were rumored to have happened there in the 1950s. We’ve also played a role in the history of rocket science; we’ve put up the Very Large Array on the Plains of St. Augustine to listen to the stars; and Richard Branson is busy building his Spaceport here to take commercial passengers to the edge of outer space. Ultimately, of course, anyone who has walked out into the New Mexico night, on a lonely roadside far from any city lights, will have experienced the sensation that the next stop is the cosmos.

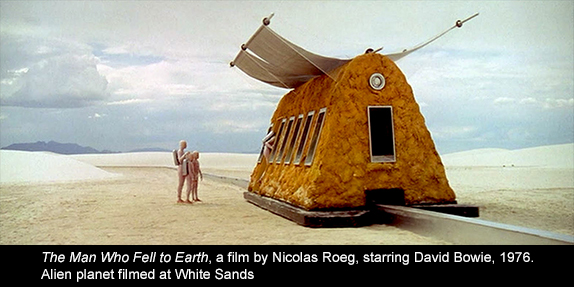

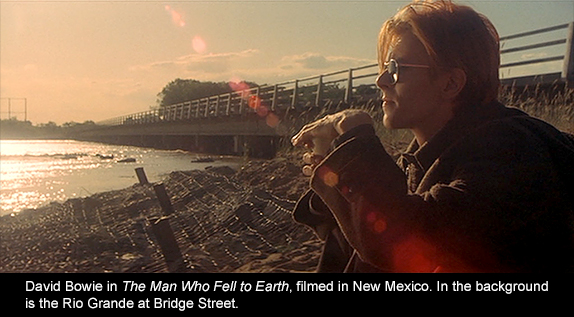

In 1976, Nicolas Roeg filmed The Man Who Fell to Earth at sites all over New Mexico. The movie’s star was the unearthly David Bowie, and I remember the pleasure of watching him turn up at many familiar places. He landed from his fall from space at the top of the coal slag pile at Madrid, and had his first contact with humans down near the Rio Grande crossing at Bridge Street. Fenton Lake in the Jemez featured prominently, as did the old Plaza Hotel in downtown Albuquerque. There was some irony to the New Mexico setting, however, since Bowie’s character was on a mission to find water for his dying planet, or was scouting a place for its weakened population to colonize as their world dried up.

In any case, I suspect that there is a ready audience here in New Mexico for films like Under the Skin, which stars Scarlett Johansson as an alien creature from another planet. Although I am a sucker for speculative epics like Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which took a feeble book by Arthur C. Clarke and transformed it into a brilliant work of art, I am not ordinarily a fan of science-fiction. So I felt (and still feel) considerable resistance to this film. Nevertheless, like it or not, the film has gotten under my skin.

Like Blade Runner, another sci-fi flick notable for its visual dazzle, the pretensions of Under the Skin toward raising issues about just what it means to be human seem to me ultimately disqualified by its chosen genre. I have little patience for the conceit of giving to the non-human the curiosity to begin to try out elements of human empathy and compassion and to take on aspects of what’s usually called the human “soul.” It’s a genre that too easily forgets all the lessons of Darwin and the cosmologists and geophysicists who have shown just how intricate the web of life actually is, and how infinite the variables that determine its appearance and evolution. It also seems willfully ignorant of the entire tradition of humanist metaphysics born of Athens and Jerusalem. In the end, the film’s chosen genre doomed it to the Twilight Zone creepiness of its last two minutes, salvaged only (if at all) by the wonderful shot of snow falling gently on the lens of the upward-pointed camera—perhaps the most breathtaking final shot of any movie I’ve ever seen.

Under the Skin was in theaters earlier this year, but I saw it as a new release on Netflix. I have not seen Jonathan Glazer’s earlier films, Sexy Beast and Birth, both of which have gotten a lot of positive discussion. But part of my resistance to the film had to do with Glazer’s major reputation for producing advertising films for TV. There remains a kind of MTV quality to much of Under the Skin that made me mistrustful of its sometimes overly self-conscious effects—many of which are truly stunning, audially as well as visually. And then there’s the problem of the early press about the film’s greatest conceit—the idea of having Scarlett Johansson disguise herself and drive around Glasgow in a van, asking strangers directions and eventually picking them up and engaging them in conversation, all of it filmed by hidden cameras. Here’s the star who fell to earth to commune with ordinary mortals, an alien in their midst. “Smile; you’re on Candid Camera!” went the slogan of the old TV show that found such great fun in examining humanity’s gullibility and automatic reactions. This conceit gave the film its basic premise of viewing humanity with alien eyes.

The film begins with a pinpoint of light on a black screen. As it brightens slightly it vaguely reveals various disks and orbs in motion and seems to deconstruct the origins of both the universe and the human eye, which appear to come into being together. (Is it the birth of consciousness? The birth of the alien protagonist? Or is it just the insides of the projector’s lens assembly?) Meanwhile, the soundtrack is a wonderful montage of thrumming musical sounds and a voice apparently trying to utter or articulate words in an unknown tongue. It’s a provocative way to introduce the visual and audial bases of cinema, and somewhat reminiscent of the deconstructive and acutely self-reflexive opening of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona. And the central business of having Scarlett Johansson drive around and pick up people from the street is possibly a reminder that film is the original body snatcher, since she lures the boys into the truck just to film them. The film is a strange mixture of the documentary and the mythic bases of film. On the mythic side is the casting of Scarlett Johansson as the alien predator. “Glamour,” after all, is a Scottish word, perhaps a corruption of “grammar” as an ancient department of learning, and its meaning is linked to occult knowledge and the ability to cast spells, producing an inexplicable allure. And surely it can be no mere coincidence that the look she adopts—with the black wig and heavily made-up eyes and lips—exactly matches that of two of the most striking artificial masks in British movies: Mick Jagger’s transvestite face in Nicolas Roeg’s Performance and that of the transvestite in The Crying Game.

In the end, the film’s greatest revelation is about alienation—how everyone is an alien being in an ever-more distanced and inhospitable world. Our present human world, the product of human artifice and ingenuity, is a place of bleak shopping malls, mean streets, and freeways, along and through which people are indifferently shuffled as if by so many troughs and funnels that are designed for the utterly utilitarian convenience of movement and for the sake of unrestrained commercial consumption by the nameless masses. Conceived of as fully interchangeable individuals, these masses of humanity are locked into a state of alienated solitude and isolation. The film is predicated on the notion that loneliness is an essential trait of the human. We see it emerge in each of the men that the alien accosts and lures into her van. They are all basically withdrawn—alienated in some way. At first they are reticent, self-conscious in their speech, and awkward in their unexpected encounter with an attractive and somewhat solicitous member of the opposite sex, especially since she has broken into their routine and interrupted their privacy. Because they are Scottish, their speech is nearly indecipherable, quite alien. But, in our society, everyone has become an outsider, an alien being. And within their self-preoccupation, everyone is convinced that they are on their own—basically unwanted, unloved, and unlovable. Human flesh is a burden, a case brought to the forefront when the alien picks up a horribly disfigured man suffering from the same rare disease as the Elephant Man.

And beyond the hardened human world that we’re shown, we’re also shown the natural world as cold and indifferent—an autonomous ecosystem of forces of wind and weather where humans have nevertheless had to try, however tenuously, to establish themselves. What better way to demonstrate the utter indifference of nature than to stage the film in Scotland in winter? It casts a pall of gloom over the entire picture and produces the film’s two finest moments: the stormy scene on the rocky beach with the ocean churning in a blind fury of dispassionate forces (and within which the desperate humans were like thistledown in the wind) and the totally opposite mood of the quietly impassive snowfall at the end.

What the film pointed up to me was that life itself is alien to the universe, which continues along on its own course, overwhelmingly and almost completely, without it. If there were to be extraterrestrial beings out there somewhere—which is apparently the premise of the novel on which the movie is based—they would have to have evolved as a totally distinct species. It is said that the original novel had a theme of aliens coming to this planet to harvest humans for food, more or less in the spirit of Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal. The film, however, is quite vague about this. It does not give any explicit purpose to the Scarlett Johansson character taking on the human form of a prostitute, nor why she is driving around in a van and seemingly seducing vulnerable men. She basically belongs to the tradition of a “femme fatale.” Like a trapdoor spider, she seems to lure the men into a dark chamber where they remove their clothes in a state of sexual arousal in response to her enticements. But all is very dark, and as they follow after her they slowly sink, naked and erect, into a black liquid morass. At one point, we are shown a couple of them, floating suspended as so much naked flesh in the depths of the liquid blackness. We don’t see them being packaged up and shipped back to the home planet for consumption. Instead, it’s as if, as one reviewer neatly said, they had entered into the black world of Francis Bacon’s paintings, which is a world conceived on the basis of individual human isolation and the vulnerability of the flesh, its mortality and its corruptibility through the imperatives of its (mostly sexual) needs. It is a world of alienation—of separateness and the consequent loneliness and suffering of the soul.

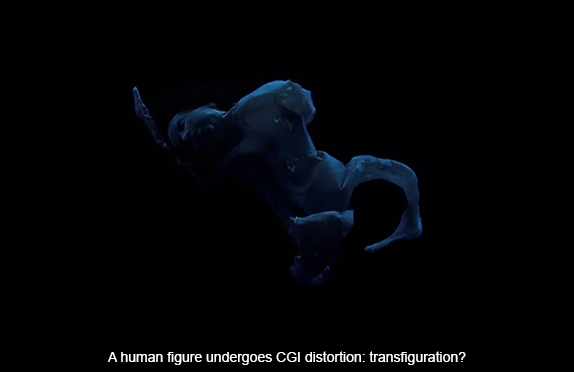

So what is that viscous blackness? Is it death? Eventually there is a sequence of CGI animation in which a naked figure in the black soup is distorted as if it were an image reflected on the surface of a wave. It shimmers around and becomes an indecipherable shape. Is this meant to imply some sort of transubstantiation? Is it supposed to invoke the way the body is absorbed into the elements after death? If that could be the case, then the mysterious and unexplained motorcyclists that hover around menacingly and seem to accompany the Scarlett Johansson humanoid begin to make more sense.

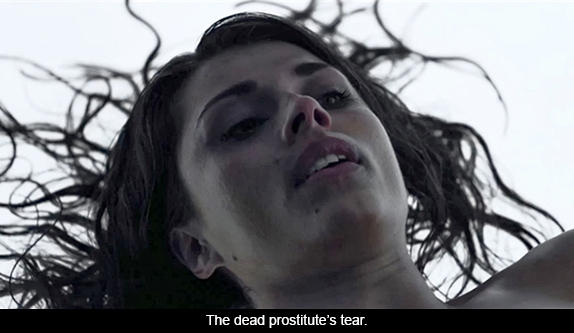

While the movements of the motorcyclists provide the film with some of its most thoroughly cinematic and stunningly beautiful images, they remain enigmatic. There’s one black-suited motorcyclist, in particular, who whizzes around and brings to Johansson the corpse of a prostitute that had been dumped by the highway. Johansson strips the clothes off the corpse in order to dress herself in them and to assume the dead girl’s character; after which she goes to a shopping mall to pick out a few accessories, like a fake fur jacket, allowing the filmmakers a chance to examine the self-alienation of the other shoppers and the people on the street. Before we cut from the scene of the prostitute’s corpse however, there are two shots that deserve our attention. One is a close-up of an ant that the alien picks off the corpse—another non-human species rapt in its own instinctual endeavors, which will prove pivotal to the movie’s meaning. And the other is a lingering shot where we get a glimpse of a tear emerging on the dead girl’s face—as if the human soul could weep at its fate, shed a tear at its own loss. (I was reminded of the extraordinary passage in William Faulkner’s The Hamlet in which a man is shot from his horse, and in his fall his entire unhappy life of missed chances passes before him—going on for more than a dozen pages—before he lands, already dead, on the ground. “His eyes, still open to the lost sun, glazed over with a sudden well and run of moisture which flowed down the alien and unremembering cheeks too, already drying, with a newness as of actual tears.”)

At first I thought that the motorcyclist was meant to represent death, like the one in Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus. And then, since there was more than one motorcyclist, I thought they were supposed to be like the Valkyries, collecting the bodies to carry them off to some Valhalla in outer space. But then I realized that they are meant to be more like the vultures that the Valkyries mythically symbolize, based on ancient beliefs that vultures carry away the soul of the dead and return it to the sky, along with the fleshy physical matter of the body that they also carry off. So the motorcyclists are like vultures or ravens or common flies, swarming around and attracted to the dead bodies, and in their indifferent predation redistributing all of the component elements of the dead back into the diversity of the universe. It was the idea of species predation that, for me, ultimately gave some sense to the film.

It dawned on me while thinking about the film’s most powerful and disturbing scene—the scene of the stormy ocean and the rocky beach, which is absolutely thrilling in its cinematic dimensions. The scene begins with the alien approaching a man on a promontory overlooking the craggy coast, under a lowering sky. She asks him about the local surfing conditions. He turns out to be a Czech, a foreign outsider like herself, but one who had come there to get away and experience the isolation of raw nature. But he is soon distracted by the drama that begins to take place in the background. Another little human family is enjoying the solitude of the cove. The woman is swimming in the waves while her husband holds their infant child and watches from the shore. The family dog has joined her in the waves, but she soon notices that the dog is in trouble, unable to paddle against the current. She impulsively begins to swim to the dog’s rescue. A drama of human compassion begins to unfold. The waves are forceful and building increasing momentum and the sound of wind and surf joins the anxiety-inducing music to overwhelm the soundtrack. Through this, however, we begin to hear the child’s crying; and the desperation of that sound, and the basic human dependency and need that the child’s crying signals, now begins to produce a highly charged atmosphere. Overcome with concern for his wife’s plight, as she, too, is caught up in the relentless power of the waves, the husband impulsively abandons the child and plunges into the churning surf. At the sight of the husband’s flailing, the Czech, too, plunges into the turbulence and manages to swim to the husband, attempting to tow him back to safety. They struggle at cross-purposes and are both dumped by the waves onto the rocky beach, where they continue to be tumbled and battered by the wind-driven waters. The husband manages to break free of the Czech’s grasp and returns to his desperate attempt to swim out to his disappearing wife. We lose sight of him as the alien approaches the now overwhelmed and unconscious Czech, pulling his buffeted body out of the pounding water and onto the beach. She looks around and then picks up a rock and smacks the Czech on the skull. She is like a grizzly bear pulling a fish from a salmon run—one species unconcerned and unaware of the life conditions of another, preoccupied only with its own instinctual need. As she is dragging the Czech away in the howling storm, the camera cuts away and we are treated to a last, dark and unforgettable insert shot of the infant child, bawling and alone and attempting to rise on the darkening beach, but helplessly unable even to walk at that dependent age.

We’ve just been treated to a harrowing experience of the consequences of human dependency and compassion in the face of the overwhelming forces of indifferent nature, acutely contrasted with the inhumanity of the Johansson character as an alien species.

If life itself is alien to the universe, then so is death. Death is life’s accompaniment, its tragic flaw and also its handmaiden, since life seems to be condemned to feeding on other life for its sustenance. Life is only concerned with its own perpetuation. Even gendered sexuality has evolved to serve that purpose of perpetuation. Knowingly or not, this seems to be one of the film’s essential themes.

It all gets muddled, however, in the film’s denouement, in which the alien begins to develop a curiosity about her human form and what might be the nature of humanity “under the skin.” She also seems to develop an aversion to her allotted mission and abandons the van. But what has alienated her from her adopted role? Something about posing as human has gotten under her skin. We see her wandering on foot in a light rain and a young man, in the casual interest of being helpful, tells her that the bus will be along any minute. She has not really been going anywhere, but goes off by herself to wait for the bus anyway in the simple bus shelter. She and the young man get on the bus, its only passengers, and the young man begins asking her questions out of compassion for her apparently depressed and withdrawn state. The bus driver tells him to stop hitting on her and move away. On her own at a truck stop, she decides to sample a piece of cake, an apparently coveted human food. But she becomes fearful of ingesting it, gags and regurgitates, much to the disgust of the restaurant’s other clients. Traveling on, she gets off the bus with the solicitous young man at his stop, and he gives her his coat and he takes her in.

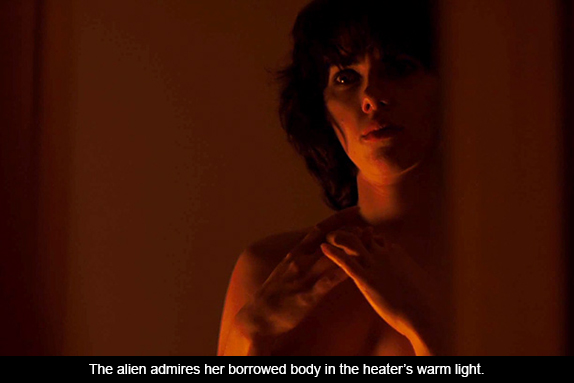

We see the cold stone wall of a ruined castle in inclement weather and discover that the young man is showing her the tourist sights of his native country. She is uncomfortable and incommunicative and buffeted by the fierce winds that howl around the parapets, and so the young man draws her away down a curving tower staircase, which she seems to be quite fearful of, and then brings her home. It’s cold and lonely there, too, and the boy brings her a space heater to warm her bedroom. In the red glow of the heater, she undresses and begins to take a serious interest in her borrowed body, becoming strangely curious and fascinated with her own voluptuous nakedness. The boy returns, seeking her sexual companionship; but when he tries to couple with her, they both remain clothed. Everything is awkward, shy, and uncomfortable. There is no sensuality and no connection—although there is penetration, for the first time in her seductions of men. She is shocked by this violation and leaps up to examine herself, holding a lamp in one hand and probing anxiously between her legs. She is no longer an intact virgin. Whatever else might be the case, she is no longer in a position of power when it comes to her sexuality, no longer the unobtainable object of desire that led all the other young men to the doom of their sinking. There is a sudden turnaround from the earlier moment when she was admiring her body in the heater’s warm light. The lamp’s light is harsh. It seems like she wants to crawl out of her skin.

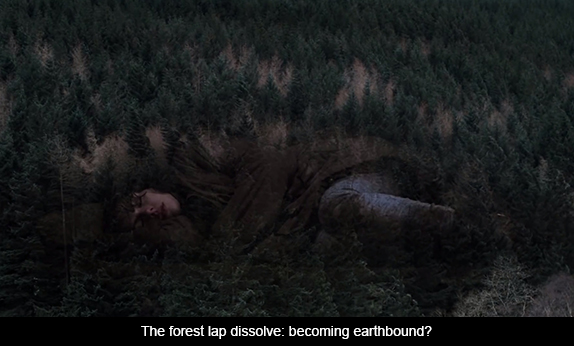

Afterwards we see her wandering alone in a cold forest of mainly skeletal black trees, her black hair wet with rain. She walks for quite a long time and eventually encounters a man with a yellow raincoat, who is passing by and is surprised to come across anyone in that stretch of the woods and in such inclement weather. He is a bit flustered and awkwardly attempts to engage her in conversation. He tells her to follow the markers and warns her not to get lost as he shambles off in the opposite direction. Soon she comes to a stone hut, empty and cold, which is provided for hikers as shelter. She lies down on a cold platform and goes to sleep. Is she becoming human, succumbing to bodily fatigue? She seems to dream of a forest of uniform conifers, glimpsed from above and blowing rhythmically in the wind like a carpet or embroidered tapestry, over which her curled form appears in lap dissolve. Is she, too, like the trees and the wind simply a force of nature, now somehow one with it? Is she, in sleep, no longer withdrawn? (There had been an earlier effect of this kind in the film, in which the face of the alien and everything around it had dissolved into a shimmering and exquisitely beautiful field of gold, like a Byzantine mosaic; but, for all its dazzle, I can’t recall when or why that occurred. Was it a moment of supernatural transformation and demotion for her, like the moment when Wotan takes away Brunhilde’s godhood and makes her mortal?) Is the alien becoming earthbound?

She is awakened by someone feeling her up. It turns out to be the man in the yellow raincoat. No longer sexually invulnerable, she runs away. He chases her and tries to rape her. As he rips away her clothes he discovers to his horror that she has artificial skin. It hangs loose, revealing something black under it. She moves away in terrible distress and begins removing the skin. Scared out of her skin? It’s as if she has to get it off herself, like Hercules trying to struggle out of the poisoned coat. A black, hairless head emerges from the rubbery skin as she peels it off, then shoulders. Is the soul black under the skin? Is she composed of the same black substance that her earlier victims sank into? Is it ultimately the blackness of death that lurks under the skin? Doffing the outward trappings of humanity, she stares at the impassive face of the Scarlett Johansson head, which she holds in her lap like Salome with the head of John the Baptist, now lost to her. Behind her, the man brings gasoline, splashes her with it, and sets her on fire. She staggers forward as a flaming creature and is eventually consumed. The camera turns from the charred spot in the white snow on the ground and follows the smoke upward. Snow then falls gently on the lens as the camera looks skyward into a cumulative blankness.

Responses to “Being an Alien: Jonathan Glazer’s “Under the Skin””