Editor's note: This week New Mexico Mercury is providing coverage on various aspects of the state's water situation. The following piece was originally published by La Jicarita on April 23rd. La Jicarita is an online magazine of environmental politics in New Mexico.

Written by: Kay Matthews

As April slides into May in the upper Sangre de Cristo watershed I’m thankful for whatever green I get: the pasture grass first, emerging almost overnight into clumps of mixed brome, rye, timothy, and various unidentified shoots. The apricot trees in the orchard are just breaking into bloom, with an intrinsic knowledge that any flower display before the end of April is a fool’s game (and they were indeed zapped last Thursday night). The ornamental forsythia at the front door flaunts this rule but unlike the apricot doesn’t have to prove its worth in fruit; its justification is its persistent yellow beauty. The unrelenting wind makes Eliot’s declaration of April being the cruelest month manifest by threatening to rip the hoop house plastic from its tenuous hold on its PVC frame.

The irrigation water in my first-in-line village starts flowing around the same time, depending on the commissioners’ adherence to formal tradition—the water isn’t released until the acequia is cleaned—or informal tradition—whoever has a direct line to the commissioners gets the water whenever they don’t have it.

Although my village lies only a few miles away from Picuris Pueblo, whose priority date is “time immemorial,” there is no question that we are literally ”first in use” in my valley, as the New Mexico water code defines priority administration of water rights. With a priority date in 1700s this village on the Rio de las Trampas gets the water first as it flows from the high Pecos peaks directly through the pastures and gardens of the village parciantes. We are allotted a certain amount for irrigation, although no meters, only gauges measure the circos that traditionally correspond to shovel widths of water flowing through our three presas, or diversion dams, on the river.

Yet the concept of “priority date” implies that the water we use we own, which is contrary to the way the acequia communities throughout northern New Mexico have always managed their water. José Rivera, in his book Acequia Culture, Water, Land, & Community in the Southwest, quotes from an affidavit submitted by acequia commissioners in the early years of the Taos Valley adjudication to determine priority dates and ownership of water:

“the aforesaid acequias by and through their fully elected commissioners agree that they will continue to follow and be bound by their customary divisions and allocations of water and agree that they will not make calls or demands for water between and among themselves based upon priority dates.”

In accordance with the traditional practice of repartimiento, or water sharing, the acequias did not want to establish a practice whereby a priority call could shut off water to “junior” water rights holders in times of drought.

The Office of the State Engineer (OSE), the agency that administers water rights in New Mexico, has also been reluctant to issue priority calls to junior users but not with such altruistic motives: junior water rights largely belong to urban areas developed after the establishment of Pueblo and Hispano acequia communities and a priority call would generate a political nightmare.

But now the Carlsbad Irrigation District (CIB) has issued a priority call on the Pecos River against the Pecos Valley Artesian Conservancy District (PVACD) and we’re going to witness a legal process that won’t be as messy as if city wells were being threatened but will provide plenty of action.

This isn’t the first time the CID issued a priority call. As I wrote about in my article “How Not to Manage for Drought in New Mexico” the state paid Texas the big bucks back in the 1980s to prevent the CID from making that call. In that case, which lingered in court from 1974 to 1988 during the infamous State Engineer Steve Reynolds’ tenure, Texas claimed that New Mexico failed to deliver required water under the terms of the Pecos River Compact. Instead of complying with the condition by enforcing the state’s priority system, which would have required acknowledging Carlsbad Irrigation District’s senior water rights by shutting off Roswell area junior wells to get water to the Texas state line, the New Mexico state legislature bought and retired enough water rights to meet the Texas water demand. It cost $100 million.

The CID has late 1800 senior surface water rights as opposed to the Roswell area farmers in the conservancy district with junior groundwater rights that, as the CID claims, are being pumped while the irrigation ditches go dry. The attorney for the CID seems to think that this time around the OSE, instead of the state legislature, is going to come to the rescue. That’s because of the Active Water Resource Management (AWRM) rules (recently upheld in a decision by the New Mexico Supreme Court), which will allow an appointed water master to implement an administrative priority cut-off date. All water rights holders whose priority date is later than the administrative date must stop using the water. This would, of course, cut off water to the PVACD, just as enforcement of the priority system would require, except that AWRM would enforce it more expeditiously and also allow the PVACD to file a replacement plan: the junior water right holder could temporarily use other senior water rights that aren’t being used, assuming it’s hydrologically viable.

When AWRM was first promulgated in 2004 many expressed concern that replacement plans denied the due process of formal water transfer protests and hearings and that it expedited the marketing and leasing of water (acequias and community ditches are expressly exempted from expedited marketing and leasing provisions). According to the OSE, replacement plans “do not adjudicate your water rights but are only an interim determination for administration and can be superseded by the courts.” Replacement plans would be limited to two years, which the OSE claimed would prevent developers from transferring water rights without a full public hearing.

So while the state moves further away from priority administration—although many would say in the wrong direction—the worsening drought continues to count coup on all our efforts at water management and distribution. According to the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) the April streamflows remain dismal. The Rio Grande Basin streamflows range from 57 percent of normal for Rio Lucero near Arroyo Seco, to 11 percent of normal for the Jemez River below Jemez Canyon Dam. At Otowi Bridge, flows are forecast at 30 percent of normal, or 192,000 acre feet (af), and San Marcial is also 11 percent of normal or 53,000 af. March precipitation was 32 percent of normal, drier than 2012. Year to date precipitation is at 60 percent, also lower than last year at this time. While snowpack is below average at 55 percent, a little better than last year, much of the low to mid elevation snowpack has already melted, much earlier than average. Total reservoir storage in the basin is 614,300 af, down from last year’s 974,400 af.

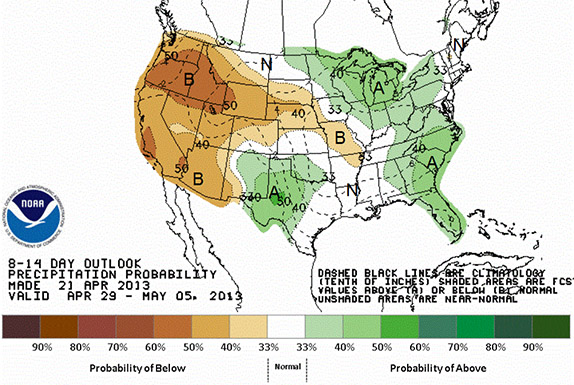

(The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association releases graphs showing precipitation outlooks several times a month. Here’s the April 29 to May 5 forecast.)

(The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association releases graphs showing precipitation outlooks several times a month. Here’s the April 29 to May 5 forecast.)

So far our solutions to this extreme drop in precipitation and surface water storage are to pump more groundwater and import surface water. Texas continues to seek redress in the Supreme Court over alleged violations of the Rio Grande Compact, claiming that New Mexican groundwater pumping below Elephant Butte Reservoir is preventing Texas from getting its required water delivery. All the water settlements thus far negotiated rely on imported water, either San Juan/Chama contract water or transferred rights, usually from agriculture.

What I also see happening, as a member of the Taos County Public Welfare Advisory Committee, which reviews all water transfer applications within or from Taos County, is that as surface waters dry up and irrigation seasons shorten, even small water rights holders are applying to transfer their surface water rights to groundwater so they can continue to irrigate via pumps instead of acequias. It all adds up, folks, and no amount of wheeling and dealing is going to change the fact that we’re in an extreme drought, the planet is warming, and climate change is upon us. I got the water last night to irrigate my field, orchard, and garlic patch, but we’ll see how long it lasts as the summer progresses. You might say my village is a kind of indicator species: when it goes dry up here it’s a sure sign there’s not much hope below.

(Creative Commons feature image via Flickr by MonaLMtz)

Responses to “Avoiding priority calls for the right and wrong reasons”