The artist is a receptacle for emotions that come from all over the place: from the sky, from the earth, from a scrap of paper, from a passing shape, from a spider’s web. -Pablo Picasso

The idea of art as therapy was established in the late 18th century when it was used as “moral treatment” for psychiatric patients. The term “art therapy” came from a British war artist named Adrian Hill who used to go out on patrols with his sketching kit in World War I and who later recognized the therapeutic value of art while he was recovering from tuberculosis. In 1945 he published a book titled Art Versus Illness. Another British artist, Edward Adamson then helped extend Hill’s work to mental hospitals in England after World War II, particularly at Netherne Hospital where his work with patients resulted in the Adamson Collection, 6,000 works done by his patients. This concept grew with the establishment of the British Association of Art Therapists in 1964 and the American Art Therapy Association in 1969, as well as similar associations in about a dozen other countries and it is now a well-recognized form of therapy. For example, the Southwestern College here in Santa Fe offers an MA in Art Therapy, focusing on “the healing process of making art.”

But what if you have one hundred mental patients and no therapist or even an instructor and can only infrequently afford the necessary paint and art supplies? That’s the situation at Vision in Action, the mental asylum I’ve been documenting and assisting in Juárez, Mexico. Pastor José Antonio Galván, a former addict and deportee founded the asylum nineteen years ago and, with only the most minimal assistance from government, has been caring for roughly one hundred patients ever since. How can he keep them feeling productive and useful? What can be done to help them get past their illnesses? An avid and self-taught painter himself, he has always believed in the power of art even if he has always had to struggle for resources. Several years ago, he had a volunteer instructor but her husband was kidnapped and she fled the country. Then a patient named Alfonso helped teach a class using instructional videos. Now he has gone. Artisan in Santa Fe provided paint at a discount but even that is very expensive. Nonetheless the urge to create art is a powerful one and has continued under Galván’s leadership. Here are some examples.

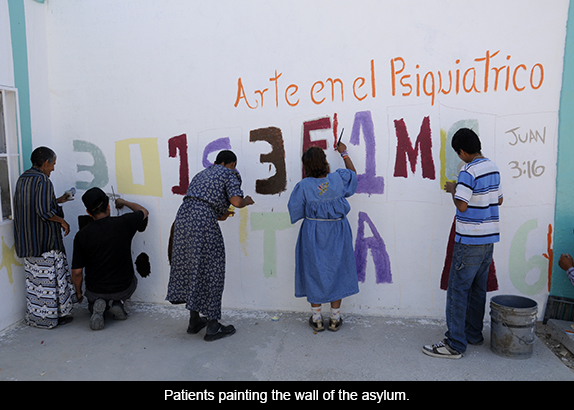

Most of these patients cannot speak coherently yet they spent hours cheerfully working together to paint this exterior wall of the asylum.

Petra has returned to her family now and seems to be doing well. Painting was key to her recovery.

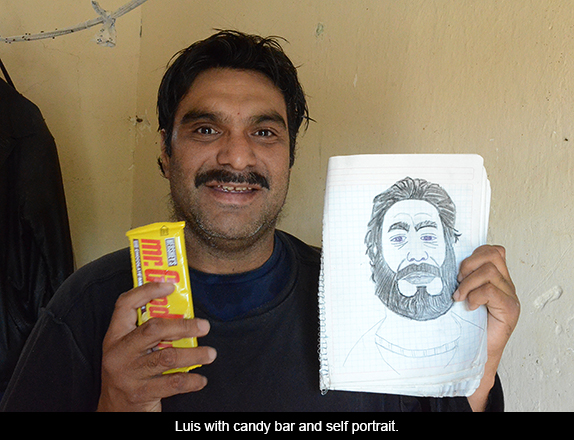

Luis is a great big, often-spooky guy who has his moods. When he is “on”, he is a key worker. When he is “off,” he stays in this cell and works on his art until he can calm down.

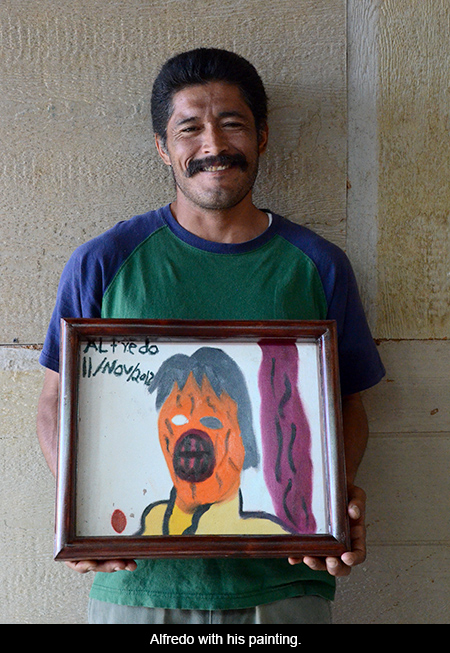

A year ago, I wrote an article entitled “The Miracle of Alfredo,” describing how Alfredo had gone into a catatonic state for several months and then suddenly recovered. In fact, he has done that several times and the other patients may have to feed and bathe him for weeks until he suddenly wakes up as if nothing had happened and goes to work. (He is very good at making cement blocks.) Recently he gave me the painting in the photo. It’s so desperate looking, however, that I have to believe these are the thoughts he has when his mind shuts down and he goes catatonic.

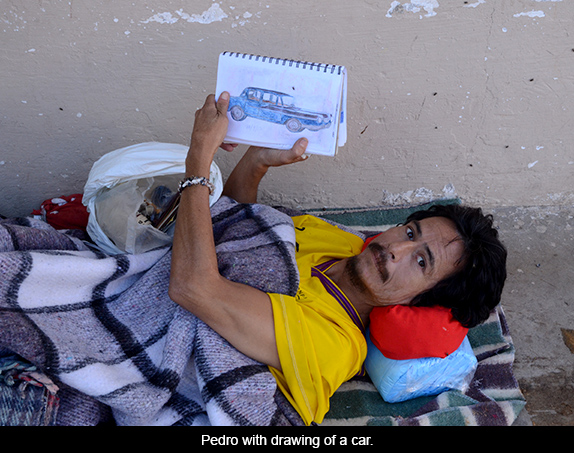

Pedro is a young guy who, besides his mental problems, lost a leg in an accident. As a result, he is either in a wheelchair or lying in bed for most of his waking hours. Art, therefore, and the feeling that he has some measure of creativity is absolutely essential to him being able to maintain his sanity.

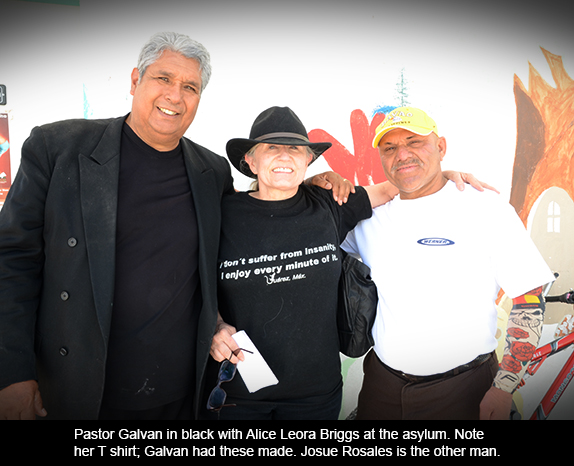

One of the key supporters of the asylum is the extraordinary artist, Alice Leora Briggs who collaborated with the now-deceased writer, Charles (Chuck) Bowden on the book, Dreamland, The Way Out of Juárez and who has had several recent shows at the Evoke Contemporary Gallery here in Santa Fe. She has just suggested that we use photos of Pedro’s art to make greeting cards.

Obviously, the asylum’s key artist is Pastor Galván not only for his own paintings but also for his support of the others. He had an earlier show in Salt Lake with the help of Chuck Bowden and now has just returned from a show of his work at the Flatbed Press in Austin, Texas. The show, put together with the support of Briggs is, as you might expect, entitled The Power of Insanity.

The key painting for me is Jesus Arm Wrestling the Devil which has a special story. One night, Pastor was sleeping at the asylum as he often does when he works late. In the middle of the night, he awoke with a tremendous pain in his right leg. As he crawled across the floor to find the light switch, a voice called out and said that it was going to defeat him. He says that the voice was the Devil and that the proof of his power was in the way Galván had painted his (The Devil’s) arm larger than that of Jesus. Galván found the light switch and immediately painted Jesus’ arm larger.

His work is harsh and not easy to sell but it sustains him emotionally and that is what counts because one hundred patients depend on him for their survival.

Responses to “Artists in the Desert”