“Adaptations – Visual Artists Work with Profound Disease and Illness,” is a group exhibition by local artists at SCA Contemporary Art (524 Haines NW). It opened on June 20th and runs through August 22nd. I found this show to be exceptional for several reasons. First because, in my experience at least, collective exhibitions rarely display such uniform artistic quality. Second, because the show’s theme is of great interest at a time when—despite extreme health consciousness, an emphasis on fitness, and organic foods—serious illness seems to be increasingly rampant (this is surely due to pollution and toxicity, excessive use of medications, and other situations endemic to the “progress” of our times). And third because, sadly, this art lover rarely visits an Albuquerque gallery and comes away so inspired. “Adaptations” is a felicitous exception to an abundance of mediocre art.

SCA Contemporary Art is a beautiful space: spacious and welcoming, and the work is well displayed. Because of its location, I doubt if the old warehouse building gets much foot traffic, but making a special trip to see this show is well worth the effort. Unfortunately, especially for a show such as this one, the gallery space is not disability-accessible. In fact it would be hard to imagine anyone with mobility problems braving the front steps. I would have appreciated a small bench or two, for sitting and contemplating one or more of the art works. And I missed a guest book in which to leave a message about how much I loved this show. Having gotten my few complaints out of the way, I’ll get on with the great deal I appreciated.

Some of the pieces in this show are constructions. Some are paintings or prints. Displayed on the floor and taking up most of its length and width is a collective installation called “Lifelines,” made by Elena Baca, Arturo Olivas, George Brugnone, Patrick Nagatani, Leigh Anne Langwell, Amy Clinkscales, and Valerie Roybal. Rope is extended in a back-and-forth pattern to signify a linear personal timeline or story, with a coil at the end to symbolize the open-endedness and impermanence of life. Rocks placed along the line serve as points of difficulty, fear, and trauma, while flowers represent points of beauty, joy, delight, relief, and so forth. Some artists have chosen to tell their story with other items as well. This installation was created as the artists worked alongside one another, evoking a feeling of belonging and community. Each artist’s experience enabled him or her or them to empathize with that of the others.

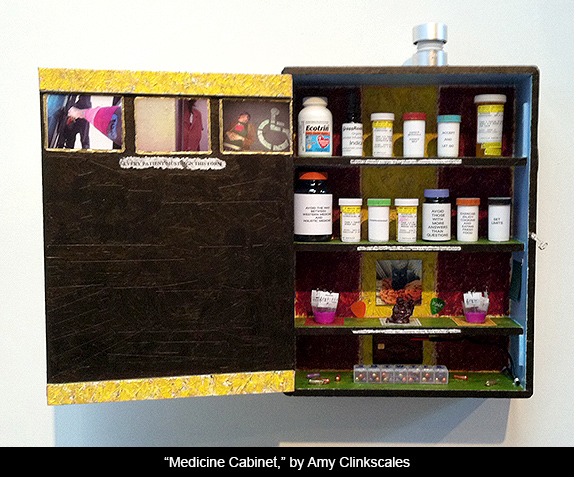

Amy Clinkscales’ piece, “Medicine Cabinet,” is particularly interesting. Upon close examination, one sees that the shelves of the traditional bathroom medicine chest contain pill bottles whose labels allude to the tension between Western and traditional remedies, as well as attitudes that are known to aid in healing. In Clinkscales’ catalog statement we read: “Bullet pierces skin. Car overturns. Tornado reaches earth. Doctor steps into a tiny, efficient room and says, ‘I’m sorry, I’m afraid it’s terminal.’ [ . . . ] In the past, my medicine cabinet was largely a place to store a few things I rarely used or thought about . . . but now I will pay it close attention.”

Heidi Pollard has three pieces in the show, one of which is titled “Chip File.” An open box sits on a small chair rooted in a pile of rough stones. Neatly filed in the box, as if they were index cards, are squares of different colored paper. Pollard says: “I am fortunate to be eleven years out from surgeries for ovarian cancer, and so far healthy. Most of the adaptations I have had to make to the experience of the disease, the ‘cure,’ and living with the consequences, have been spiritual and emotional. However the Chip File included here is a pragmatic response to several frustrating and frightening years of fragmented memory, during which I had to learn to do many things anew, including how to paint. Color had been something that was easy for me to imagine and create. But I lost that natural facility with my short-term memory loss. So I started making paint chips to help me find my way back to colors and color relationships [ . . . ] I still use and add to these chips.”

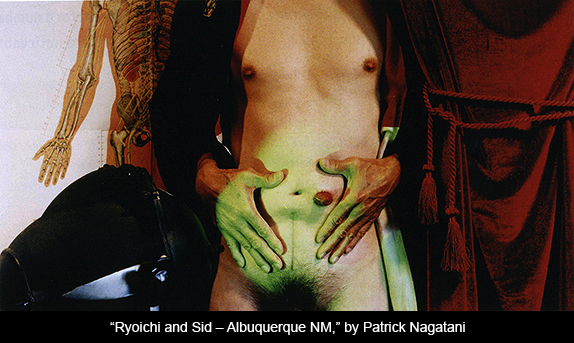

One of the pieces in the show that affected me most powerfully was Patrick Nagatani’s “Riochi and Sid – Albuquerque, NM.” Nagatani is a well-known photographer, and this is a large color print. In his artist’s statement, Nagatani writes of his interest in the healing power of chromotherapy: “I am intrigued with color healing and growth through colored rays because of the existence of duality between colored lights used in this ancient medical practice and the phenomena of light as the essence of photography and color as a translator of that essence in my life-long work as an artist. I am not a color healer, I am a color imagist [ . . . ] the piece “Ryoichi and Sid – Albuquerque, NM” was taken a month after Ryoichi (me) had his rectum removed and an ostomy created. This was a result of colorectal cancer. He calls the stoma that he embraces Sid. Now, 8 years later, the cancer has reappeared in his body and is considered metastatic Stage 4. Adaptation, healing, impermanence and uncertainty are even more important issues today for Ryoichi, both in his/my art and life.”

I found this image particularly interesting in light of the current news craze depicting images of slim female models with ostomies and wearing bikinis. Their stomas are neatly covered by clean-looking patches. One such covering was a designer patch in an American flag pattern. A serious medical condition becomes a fashion statement. Nagatani’s self-portrait stoma is a red ball, the antithesis of its commercial culture counterpart. It is commendable that a number of young women with ostomy or colostomy bags are willing to pose for fashion photographs. But Nagatani’s photo is more frighteningly real and thoughtfully provocative—as only good art can be.

Not all these artists are referencing their own illness or disability. Some use their art to speak of their adaptation to a loved one’s condition. Linda Mae Tratechaud accompanies her freestanding construction, “Bed Jacket & Pill Reliquary” with the following explanation: “In response to my mother’s escalating, multiple chronic diseases, I have adapted from being an emotionally frustrated, impatient, and intolerant daughter to an efficient, compassionate, and tender caretaker. I have watched my Mother transform into a tiny, frail, dying woman, and yet still neither of us can grasp her immanent death [ . . . ] This piece represents a delicate armor that I wish could protect and comfort her from her debilitating anxiety and fear of death. At the same time, it represents how her illness has become her identity.”

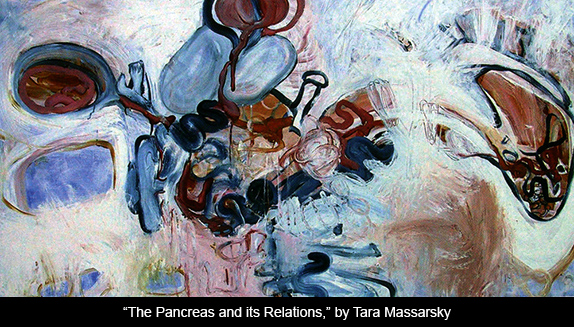

Tara Massarsky has some of the most painterly pieces in the exhibit. Her series Anatomika Abstracta was inspired by the chronic illnesses of her husband and friends. She applies a masterful knowledge of paint to what she calls “a magical process, creating images that have to do with the energies in the body, energies that we experience in many ways, physical, emotional and spiritual [ . . . ] With the series Anatomika Abstrakta, I specifically used the ideas expressed by astrology (the art of judging the influence of the stars upon human affairs), alchemy (the science of transmutation of matter and spirit), and tantric thought (Hindu and Buddhist beliefs concerned with powerful ritual acts of body, speech, and mind). I’ve tried to balance these philosophical ideas about the body/soul connection with a grounded visual discovery of the human form, while looking for a fine balance between the sublime and the grotesque.”

Randi Ganulin’s work is also informed by another culture, in this case “the ancient Sumerian myth of Inanna, goddess of love, war, fertility and lust. In the myth, Inanna journeys down into the underworld to visit her sister Ereshkigal. Step by step, she is stripped of her clothing and jewelry until finally she stands naked in front of Ereshkigal and the seven judges known as the Anna. They rule against her and she is turned into a corpse left to hang like a piece of meat from a hook down in the bowels of the underworld. Eventually, Inanna is rescued by two tiny creatures taking the form of a pair of houseflies. They bargain with Ereshkigal for her release and bring her back up to the earth’s surface, where she is brought back to life and reborn.”

The Inanna myth speaks to our struggle with illness, disability, and the range of “cures” we are offered. In our consumer society, illness itself is a commodity. And its prevalence supports whole industries: from healthcare to insurance and pharmaceutical companies, reconstructive surgeries to vitamins, supplements, and all manner of New Age healing protocols. All these artists, in one way or another, seek the experience beneath the hype.

The contributors to this show are Dana Burgy-Gautschi, Heidi Pollard, Tara Massarsky, Leigh Anne Langwell, Lea Anderson, Valerie Roybal, Linda Mae Tratechaud, Barbara Crawford, Amy Clinkscales, Randi Ganulin, Andre Ruesch, Patrick Nagatani, and Carol Chase Bjerke. Each is a consummate artist. They have used their creativity to come to terms with chronic or terminal illness, or the illness of family and friends. Their work moves beyond their personal stories to all of us, living as we do in a world where illness and loss are ever more pervasive.

Whether or not you have a particular interest in the anatomy of the body, illness or disability, whether or not these works of art feel relevant to your own experience, I highly recommend this show for what it says about the quality of art in Albuquerque.

Responses to “Adaptations: Visual Artists Work with Profound Disease and Illness”