On October 11, 1981, the second day of what was to have been several months of joint fieldwork in a remote region of the Philippines, Renato Rosaldo’s wife and companion anthropologist, Michelle (Shelly) Rosaldo, fell from a precarious trail to her death 60 feet below. These are the facts. Suddenly, the woman he loved was gone, their two small children motherless, their immediate and long-range future dramatically reorganized. A place waiting to be known. Emotions forming, fading and being replaced with others. A language only just beginning to be learned (the language of loss as well as that spoken by the subjects of their fieldwork). Consciously and unconsciously, a series of ethnographic poems began to take shape: the illusive or persistent story behind the facts.

When we lose a great love, our first impulse is to find a way through the grief—and the rage within the grief—for ourselves and then also for others who loved the person who is gone. When the loss is sudden, and perhaps especially when it wears the terrible clothing of “if only,” the grieving may take unexpected turns. All such loss, however it may strike, is traumatic. It feels like everything all at once. Over time, one begins to disentangle the tight knot of that everything and a response unfolds. It may be compartmentalization or silence. It may be a new love, surely holding the old in its arms. And, depending on the need, circumstance, and creativity of the person who has suffered the loss, it might also emerge as art that can be shared with others.

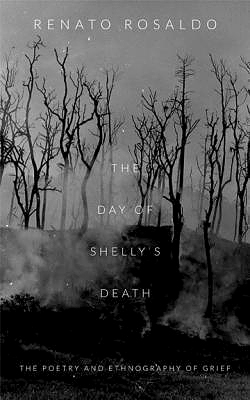

In The Day of Shelly’s Death (Duke University Press, 2014), Renato Rosaldo calls on his most painful memories and all his skills—as poet and social anthropologist, as husband, father and someone who sifts through time and feeling in multi-faced testament—to give us the finely woven layers of a tragic event and the people who inhabited that event. The book combines a timeline, two essays, photographs that bring the reader to the otherness of place (including a number of marvelous portraits), rough hand-drawn maps that attempt to trace the moment of disaster, important notes, and index and, quite centrally, the poems. Many of these are written as imaginaries from the perspectives of his children (5 years and 14 months old when their mother died), a kind companion, an opportunistic “helper,” the forensic official, a field mouse, and the cliff itself. This is genre-bending in the most meaningful sense of the term, not because the author wanted to explore his subject matter in a variety of genres, but because he has expertise in a number of fields and that expertise very naturally rose to the surface here.

Jean Franco, in her perceptive foreword, writes that Rosaldo’s poems: “[ . . .] expose the hollowness of ‘coming to terms’ or ‘getting over it.’ [ . . . ] [He] uses a metaphor from photography, ‘depth of field,’ to express what he strives for in this mourning poetry in which his grief does not occur in isolation but ripples outward and is witnessed.” (p xvi) The poems themselves span many years. Shelly died in 1981, and it was 2009 before Rosaldo was able to respond to a long deferred need to use his poetic voice. He subtitles his book The Poetry and Ethnography of Grief.

So many volumes of poetry and prose have been written about death, dying, and the grief it leaves in its wake. I think of Dylan Thomas’ Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night and Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish. I remember John Donne’s “No man is an island, entire of itself . . .”, Violeta Parra’s “Thanks Be to Life,” and Paul Monette’s beautiful Elegies for Rog; particularly these latter because—like Rosaldo’s poems—they focus on the details, the intimate part of the experience where so much of what informs it resides.

When I think of texts that attempt prescription or instruction for finding one’s way through the aftermath of loss, what comes to mind is Robert Frost’s “the best way out is always through,” the Chinese proverb of unknown origin that reads: “You cannot prevent the birds of sorrow from flying overhead, but you can prevent them from making nests in your hair.” And especially A.A. Milne, who put the following words in Winnie ther Pooh’s wise mouth: “Promise me you’ll always remember: you’re braver than you believe, and stronger than you seem, and smarter than you think.” Because dealing with loss is very much about memory, remembering, literally reconnecting the disperse members of a being in grief.

The Day of Shelly’s Death remembers. And it re-members, that is, it reconnects the pieces of broken, fragmented experience. One of the poems in The Day of Shelly’s Death that powerfully captures the interstices of memory is “The Ifugao Men” (p 66):

They heed Conchita’s call,

run to the riverbank,

squat, look upstream,

talk in low tones, intercept

the American woman’s body

washing toward shore,

carry it to land, form a circle,

stand silent. Conchita arrives

with a pale, trembling man.

He places his lips on the body’s lips,

rocks back. A fly buzzes

in then out of the body’s mouth.

The pale trembling man is the poet. He is also the man who loves and is now beginning to mourn the loss of the American woman, now a body. The image of the fly, buzzing in and then out of the body’s mouth, perfectly evokes death’s frontier.

“The Cliff” (p 84) is written long and narrow on the page:

I stretch

from precipice

to river

the American

woman fell

along my

rocky spine

contusions on

her face

no autopsy

no way

to check

for water

in lungs

to know

if rocks

or river

the cause

of death

but I

am blamed

though I

never wanted

this day

of lamentation.

Each brief line holds two words, precisely two, as if the poet is desperately trying to reclaim the duality that has so horrendously been reduced to one. The cliff, not wanting to be blamed for the accident, stands in for all those, close or far, who cannot help but remain burdened by “if only I had said this or done that.”

After setting a bucolic scene of afternoon napping with his small sons, “The Omen of Mungayang” (p 53) introduces the fly that will appear in the later poem. In this poem’s last three stanzas we get one of many versions or angles of that moment of no return. We also get a further sense of how complex the layers of loss are :

[. . .] Conchita

steps into the hut and rasps, She fell

into the river. I run, reach Shelly’s body, drop

to her side. A fly buzzes in, then out of her mouth.

Back on the trail, Shelly’s voice, not the wind, her voice

echoes from death. I rush

to our sons.

Conchita’s cousin lifts Manny on her back,

then crumples in sobs.

I put Sam on my shoulders, tell him his mom is dead.

He wants to know when he will get a new one.

Rosaldo’s children, so young when they lost their mother and in such unfamiliar territory, figure frequently in these poems. “Sam,” (p. 95) is sparse and to the point:

He asks me, his father, when

he will get

a new mother.

He sits straight, protects

his brother Manny,

pushes my hand

that seeks to comfort.

The shoes I chose

slid off

the crumbling trough.

He speaks

my unspoken thought,

says he wishes

I had died,

not her.

Not all these poems are tributes to or evocations of the beloved family and friends who were deeply affected by Shelly’s death. “Jun Dait” (p. 81) is a case in point. It begins: “I’m a big man here in Kiangan, / my body has heft. / That Ford Fiera is mine. // I met Renato at Skyland Travel in Baguio, / invited the family to stay in my home, / makes me look good.” Then, after a couple of stanzas describing his important business holdings and intention to run for political office, the poem’s voice continues: “That damned American / will never thank me enough. / I’ve opened my house to him. // Now I accompany him, Kiangan / to Bayombong and back, late at night / to avoid traffic at checkpoints // where I tell the soldiers / why there is / a corpse in our car.”

Many, though, record acts of generosity and kindness in a time of terrifying need. “The Tricycle Taxi Driver (p 73) tells us: “[ . . .] In Lagawe I own the only / tricycle taxi, orange, yellow, read, / fresh paint, curving lines. // [ . . .] I shall be the one. // In a rattan hammock tied to a pole / Ifugao men bring the woman’s body. The American man shoulders // his five-year-old son, / his walk heavy, shirt soaked, / face streaked with dirt, // his tears behind red eyes, / then he mumbles, / Taxi and steps toward me. // He places his two sons on the seats, / then sits between them, offers to pay. / I’ve come here to give him a ride. // Please accept my gift, I say.

At the end of this stunning book, Rosaldo includes two essays. In the first, “Notes on Poetry and Ethnography (pp 101-113),” he writes of his conviction that: “The material of poetry is not so much the raw event as the traces it leaves.” and “The ambition of poetry is [ . . . ] to be the event itself.” I heartily agree. And I believe Rosaldo has achieved these aims magnificently.

The second essay, “Grief and a Headhunter’s Rage: On the Cultural Force of Emotions,” was written much earlier than the poems and is reprinted here. In it, Rosaldo draws on his fieldwork with the Ilongot men of northern Luzon, to probe the custom their ancestors had of violently beheading random humans as a way of dealing with the rage that lives inside grief. In this book, this important essay provides a further bridge between the reader and a people and history that may seem jarringly “other.” Talking about The Day of Shelly’s Death with a friend who is currently writing about loss, she wondered about this choice to place poems first and prose texts at the end of the book. In this particular case, at least, I think it works perfectly. As does this whole extraordinary book.

Responses to “A Review: The Day of Shelly’s Death”