Yeira pulls back a strip of chicken wire and points into the little pen. There is Melissa, a tiny pig. She had been given to Yeira and her family by Pastor José Antonio Galván, the founder of the nearby mental asylum, Visión en Acción where Yeira’s grandmother, Elvira once worked as the cook. They, in turn, were going to fatten Melissa for a birthday celebration for me next January. This is not only an extraordinary gift from this impoverished Juárez family but a new insight into the role of animals here.

Yeira (15) lives with her grandmother, Elvira on the west edge of Juarez just a few miles from Visión en Acción. Her brother, Hector (16) has dropped out of school to help the family and now lives and works at the asylum.

I met Yeira and Hector three years ago during my first visit to the asylum. They were in the patio where most of the patients spend their days, talking to a man named Adolfo who was called the Spiderman because he had a spider tattooed on his neck. I assumed that they too were patients and only learned later that Elvira would bring them to the asylum when she worked on weekends because it was safer than having them stay at home in their dangerous neighborhood. It stunned me that kids this young would spend their weekends in a mental asylum mingling with patients like Adolfo who had spent half his life in prisons and mental hospitals. Since Yeira is exactly two weeks younger than my granddaughter who lives in Denver in totally different circumstances, I began to take an interest in helping this family.

Once or twice a month, I bring beans, rice and used clothing that has been donated by friends here in Santa Fe. They can hang it on the fence outside their house and sell it on Sundays. This winter they were scrounging up dusty chunks of plywood to heat their home so I’ve been driving them to a big rotunda to the east where we can buy decent firewood; mesquite is the best. In addition, they do writing projects for me like interviewing patients and I pay them in cash. Hector and Yeira both love animals and would make wonderful veterinarians but there’s no market for that kind of work in Juárez.

The tiny Melissa, however, symbolizes a larger plan of Pastor Galván’s. Feeding one hundred patients every day is a staggering expense so he hopes to become more self-sufficient by having this growing number of chickens, pigs and goats. It also provides work which he believes is an essential part of treatment. “Work,” he has said repeatedly “makes you feel productive, gives you dignity.”

Because he has so little money and receives almost no government support, his patients essentially run the asylum. This includes preparing and serving the food, washing the blankets and clothing, shaving and cleaning the less capable patients, bringing in firewood from the desert and repairing vehicles. As dawn breaks, patients, many of whom can’t speak coherently, simply get up and go to their tasks. I’ve also watched them care for other patients, consoling and calming them when they become agitated, and applying affection and care rather than the force we would use in this country. It’s much more effective than having a couple of burly orderlies restrain a patient and something we could learn from.

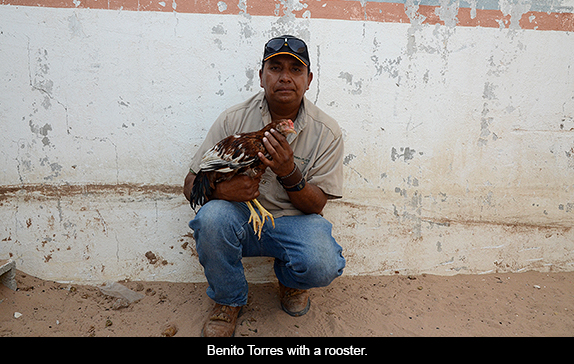

Galván put a powerful 38 year old patient named Benito Torres in charge of these chickens, pigs and goats. Once Melissa gets too big for Yeira to care for, she’ll rejoin the other pigs under Benito’s command and live there until next January when she will be killed for the birthday fiesta. Benito, however, is an example of the third benefit of these animals. He spent many years working on farms all across the US and was in charge of crews of migrant workers at a very young age. Then something dark happened. Drugs, alcohol, a murky story about a death in the state of Washington and then deportation. He ended up in the asylum and, for about ten months a year, was one of the key workers, a man with obvious leadership skills.

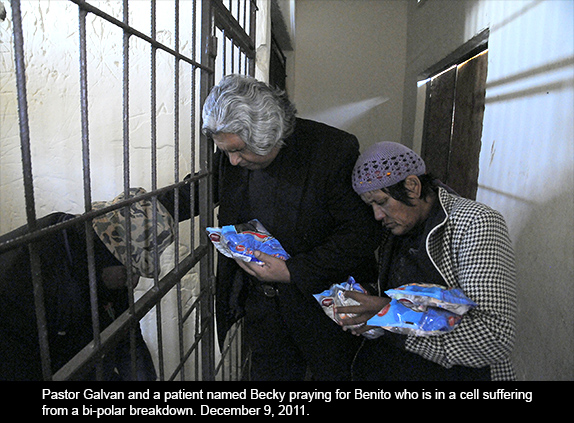

The problem was that he would have a bi-polar breakdown every winter and have to be locked in a cell for as long as two months at a time in order to calm him down. (Galván is unable to afford the more advanced and expensive medicines that might calm someone as potentially dangerous as Benito.)

When Galván put Benito in charge of the animals, this third benefit – therapy – quickly became obvious. Benito hasn’t had a bi-polar incident since. His two main assistants, Memo and Mendoza, neither of whom can speak coherently, are both doing much better now that they are working with the animals. Benito takes good care of them and is always asking me for treats like chocolate and cigarettes that he can give them as rewards.

So in a way, this tiny Melissa symbolizes a kind of therapy that really works. Her death at the asylum in January 2015 will be a special event and in the space of two or three hours, she’ll go from a squealing animal to delicious carnitas for 100 patients. But it won’t be without its sadder side. When we last killed a pig, one of the patients pulled me aside and said, “It has never bothered me to put a knife in a person but the idea of killing a pig! Or a chicken! I can’t imagine it.”

Responses to “A Pig named Melissa”