The rain started before dawn—a pounding bitter cold downpour—so Pastor Galván and I decided to forego the pig roast. Therefore, the huge El Chino got to live for at least another week.

It was January 30, my birthday and many months ago the patients at Vision in Action, Galván’s mental asylum in Juárez had promised me a fiesta and pig roast in celebration. Although I have no interest in birthday celebrations, this was a gesture of kindness that I couldn’t resist. I mentioned it to a number of friends and many showed up—my college roommate from Brunswick, Maine, my sister from Carbondale, Colorado, my oldest son, Jay, his wife, Jenny and my thirteen year old grandson, Walker from Denver as well as others from El Paso, Santa Fe, Lubbock and Colorado. Irrespective of the pig roast, I wanted them to see the extraordinary work that Galván has been doing for the mentally ill in Juárez for almost two decades now. But I was also very concerned as to how they would react. This is not like the United States where a facility like this would be relatively neat and clean, there would be staff with uniforms and it would receive some fixed and reliable reimbursement for each patient. Here in Vision in Action, discarded vegetables are used for food, patients function as staff members, everyone looks ragged in the odd medley of cast–off clothing, and many of the men are jammed in one large room where they have to sleep on mats on the floor. Nonetheless, there is a sense of caring and dignity here that is far more important than the status of the facilities.

Would my friends see this or would they just be focused on the physical conditions? Would they understand what life would be like for these patients if it were not for this facility—living on the streets of Juárez, subsisting on garbage, always in danger of being killed by gangs? Would they sense Galván’s constant struggle for money to keep the buildings heated in the biting cold of the desert winters or to buy medications or gasoline to transport patients to hospitals?

When we entered the main patio where most of the patients spend their days, several rushed forward to greet us. One—a stocky young man named Yogi—can only make shrieking noises but they’re noises of pleasure and excitement. To him, the simple fact that we have come from outside to visit him and to show we’re interested in his life is a source of great pleasure. He immediately asked me to take a photo of him and my grandson, Walker.

A tiny woman named Elia Zoto comes over and hugs me. She can only say two or three words but she has an innate sense of when other patients are hurting and knows how to console them. As a result, she is more effective in terms of keeping patients calm than a burly orderly with a needle full of medication would be.

Walker then takes one of the bags of candy I’ve brought and begins to distribute it. To my great pleasure, he seems totally at ease here.

Galván shows my friends everything. This isn’t like one of many legislative tours I went on when I was a State Representative and serving on Colorado’s Joint Budget Committee, tours where you would be carefully steered away from the trouble areas. For example, he shows us the large room where the men all sleep on mats on the floor, warm but jammed together. Should they have to live in these conditions? Of course not but how are we going to raise the money for a new building for them?

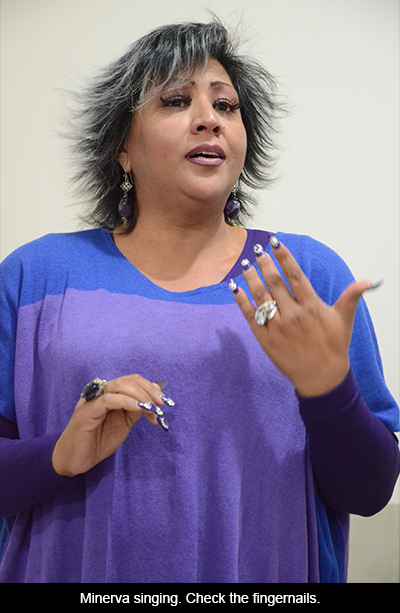

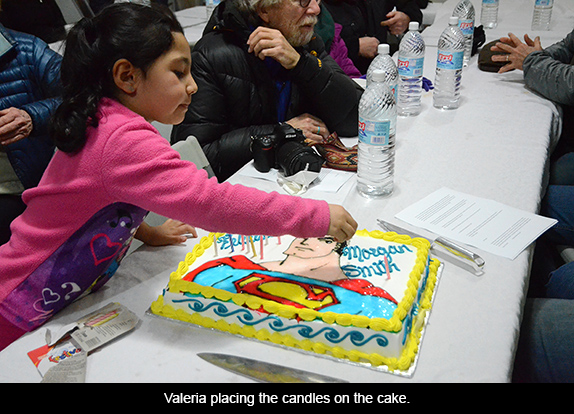

We then go into a room where folding tables have been set up and a huge cake faces us. Two striking looking women and a young girl stand by the wall. One of the women is Minerva Perea, a soprano who sings in an opera group at the University of Juárez. The other is her sister, Jezabel whose daughter, Valeria carefully places the candles in the cake. Galván starts a short sermon. A woman named Megan Culip translates. She is a chaplain in a 500 patient state mental hospital in New Jersey, has come out at her own expense to learn about Vision in Action and will be spending a week.

I’m not a church person but what I’ve learned in these many years of border visits is that people of faith are the ones who have the courage and persistence to take care of those who have been abandoned by their governments. On the border, those people of faith are not only Mexicans like Pastor Galván; they’re also unique people from Santa Fe like Jim and Pat Noble, Eunice Herrera, Carlos and Hector Garcia and Lydia Pendley. As a life-long Democrat and someone who served many years in different levels of government—the US Army, the Adams County Public Defender’s Office and mostly the state of Colorado—I see now that simply creating and funding a government program doesn’t work unless you have people like the ones I’ve mentioned who are truly committed to caring for people. Look at New Mexico, for example, which has taken its millions of dollars for mental health and created nothing but chaos. My family and friends saw this commitment on January 30 when they visited Vision in Action and I want to thank them for coming.

Responses to “A Birthday in the Desert”