Back when digital metadata – digital anything – was purely theoretical, along with smartphones, the Web, and computers smaller than refrigerators, when Steve Jobs and Bill Gates were still in college and Edward Snowden hadn’t been born, a crew of community organizers put up a bunch of billboards in Albuquerque. Each sign bore only one image: a giant eye.

After the billboards went up along heavily trafficked roadways in New Mexico’s biggest city, still something of a Route 66 way-station at the time, New Mexico TV and radio stations started carrying public-service spots warning that everyone was under observation.

This is hardly news today, but the billboards and broadcast warnings date from 1974. The anti-surveillance activists were community organizers based in Santa Fe – then still a lefty-bohemian hub - who got interested in the topic because they worried about government agencies and corporations systematically scooping up data on individuals. Capabilities for doing so were, by today’s lights, almost comically primitive. Way ahead of their time – too far ahead, in fact - the Santa Fe crew founded the anti-mass surveillance movement.

Along with the billboards and broadcast spots, the activists launched some balloons with the eye logo as part of a campaign to draw attention to surveillance. Godfrey Reggio, to become a celebrated film director a few years later, was the campaign’s sparkplug. “Having worked as activists,” he says, “we could see what the police was doing, what the government was doing, keeping records on everyone.”

A short time later, Reggio went on to devise and direct Koyannisqatsi (Life Out of Balance), followed by Powaqatsi (Life in Transformation) and Naqoyqatsi (Life as War). The now-classic movies, scored by Phillip Glass, show technology upsetting the natural order of life. His latest film, Visitors, is described as portraying “humanity’s trancelike relationship with technology.”

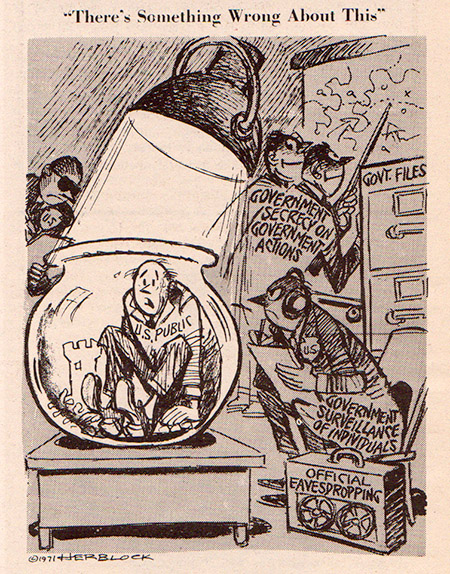

Reggio’s obsession with the subject grew out of his work on the anti-surveillance campaign. Automated data collection and storage, he and his friends came to realize, were signs that surveillance was growing beyond observation of individuals. The Watergate scandal was still resonating, and grimy details of FBI espionage and dirty tricks aimed at dissidents or suspected dissidents had been coming to light for the past several years. But with a nod to Orwell, who had predicted universal surveillance, the campaigners noted that 1984 was only 10 years off. “Government was just beginning a campaign to make the Social Security number a universal identifier,” Reggio says, in the Santa Fe warehouse studio that’s been his office since the 1970s. “It became a way to track everyone.”

Remote, provincial New Mexico might have seemed an unlikely launch site for the campaign. In fact, it was ideal. An Old West tradition of minding your own business still ran strong. That frontier discretion and the state’s isolation had long attracted hush-hush government high-tech work, making New Mexicans more than a little familiar with security protocols.

The Manhattan Project (which became today’s Los Alamos National Laboratory) was located 35 miles north of Santa Fe. Its staff included one of the pioneer theorists of electronic computing, John von Neumann. The atom-bomb project in turn served to propel expansion of the security state, after code-breakers in the Army ancestor of the NSA discovered how thoroughly Soviet spies had penetrated Los Alamos. By the 1960s, Holloman Air Force Base near the White Sands Missile Range – not far from where Robert Goddard refined his rocket designs in the 1930s - would become the Air Force’s drone development lab. One former Missile Range scientist was an early mentor to Jaron Lanier, the video-game and artificial-intelligence pioneer, who grew up in Mesilla Park, NM in the 1960s and now criticizes the data-driven society. “You're being observed by cameras,” Lanier said on NPR’s The Diane Rehm Show, sounding like an updated version of the Santa Fe campaigners. “Your emails are being scanned these days. Everything...everybody wants data. Every time you go on a new site, there's little spying services that are tracking where you go.”

The 1974 campaign drew a strong response at first. The state chapter of the ACLU, which sponsored the drive, grew by 70 members in the three weeks following the broadcast spots – a big deal in a small state. But the moment passed. Nancy Hollander, a Students for a Democratic Society veteran who was state ACLU director, recalls that a good number of those newly minted ACLU-ers were right-leaning libertarians who didn’t renew their memberships. Hollander is now a criminal defense lawyer representing one of the key figures in disclosure of U.S. government secrets – Pvt. Chelsea Manning. The national ACLU, which had discussed opening a national campaign based on the New Mexico model, dropped the plan after a leadership change.

So the prescient anti-surveillance campaign morphed into the “Qatsi” filmmaking project. In fact, the anti-surveillance “commercials,” included on the boxed-set edition of the Qatsi films turned out to have been draft versions of the movies. One commercial is available together with a Reggio interview below:

As their titles suggest, the films grew out of a Native American-inspired vision of human coexistence with nature. New Mexico’s mountains, mesas and desert tend to get you thinking along those lines. The setting had drawn the adventurous, artistic and unconventional for years.

Reggio was more or less representative of the type, though he got to Santa Fe in 1959 not on his own but on assignment by the Christian Brothers, the Roman Catholic religious order he belonged to at the time. Reggio quit the order, to take up organizing against police brutality in the Santa Fe barrio. One of his fellow activists, Daniel Leibsohn, fresh out of graduate school at Harvard, introduced Reggio to the work of Jacques Ellul. A French historian, sociologist and Protestant theologian, Ellul had written a book examining the history and effects of technological development. Technology, he argued, reinvented the civilizations in which it originated, in part by enabling a vast expansion of State power. “Our deepest impulses, the most secret beatings of our hearts,” Ellul wrote in 1960, “our intimate passions, are known, published, analyzed, used.”

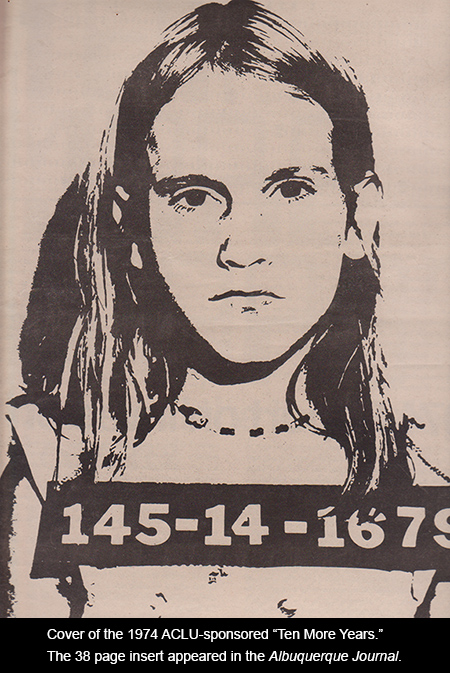

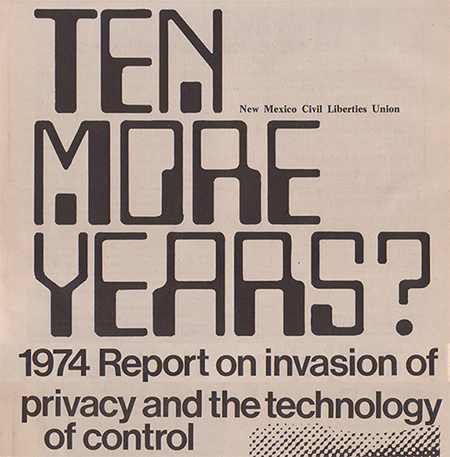

Ellul’s book was long and dense. But Reggio and his friends were convinced that some of the Frenchman’s ideas could be popularized. They were also sure that the general public would be roused by evidence of mass surveillance. Hence the billboards and broadcast spots, as well as a supplement distributed by the conservative Albuquerque Journal, the state’s biggest paper.

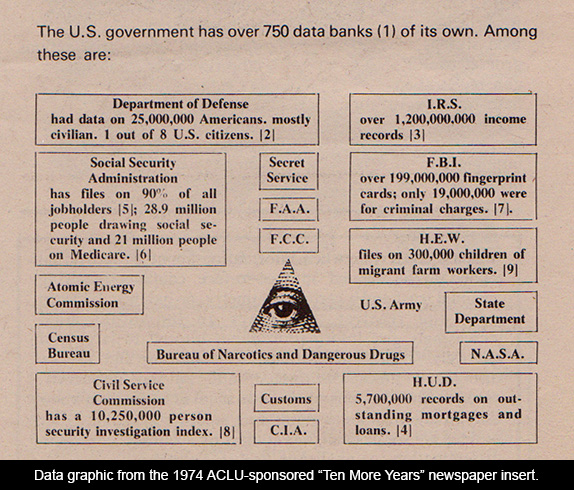

The newspaper supplement, which Leibsohn wrote, reported that technology was allowing surveillance to weave itself into the fabric of modern life. Newly developed surveillance products included “a system enabling policemen to write messages through their radios,” and “a portable color video tape recorder and camera, weighing 21 pounds.” Not only that, but “TV cameras can be made that fit into a shirt pocket.”

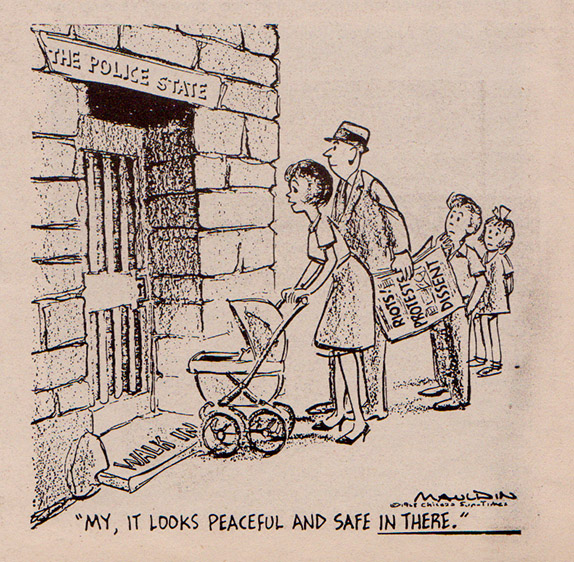

That wide-eyed amazement sounds charmingly quaint, 40 years later. But the deeper points the campaigners were making still resonate. Slipping through the net had become virtually impossible, Leibsohn wrote. Americans faced the “danger of gradual and subtle erosion of rights,” he said. “We are not dealing with rabble-rousing, would-be dictators, but quiet, hard-to-detect infringements involving complex technology and science.”

To be sure, the campaigners saw surveillance as something imposed from above. They didn’t foresee that people eventually would willingly cooperate with their watchers. “Nineteen eighty four was the emblematic inspiration,” says Reggio, who doesn’t carry a smartphone or manage his own email. “The form that it’s evolved in now is only the enrichment of what we were talking about; we’ve become the environment we live in; all these things are given to us and become natural. We do give away our privacy with everything we do with our credit cards, our Social Security number, Facebook and social media.”

The campaign got some news coverage, in the Washington Post, and elsewhere. But it didn’t make a big splash. Not big enough, for example, to persuade a Harvard dropout and some friends that Albuquerque wouldn’t welcome them as they worked on launching the startup they named Micro-soft.A plaque (stolen in 2012) marked the site where Bill Gates and his team started their little company.

The anti-surveillance campaign, for its part, left no monuments, apart from the broadcast spots. The newspaper supplement, the most detailed explanation of their work, was a pre-digital product.

The full segments as they appear on the Qatsi trilogy DVD set:

Responses to “1974 New Mexico Campaign Warned of Surveillance State”