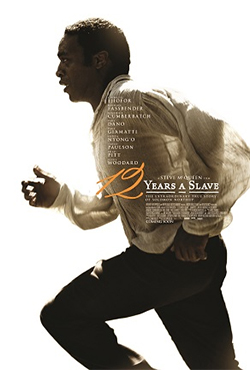

If you were to judge the movie by its trailer, you would expect 12 Years a Slave to be a Spielbergian epic—pretty in the wrong places and sentimental at its core. You would be mistaken. Director Steve McQueen’s film is an unsparing look at the dark heart of slavery and its devastating effects on all touched by the institution.

The physical suffering of slaves is graphically depicted, but this movie illustrates that the greater injury is psychological and emotional. It is not simply bodies that are being damaged; it is souls.

In most movies about Africans or African-Americans made for mass audiences, we are invited to see the black experience through white eyes. It can get embarrassing, as in Cry Freedom or Mississippi Burning, where the whites take center stage. Here, we experience slavery through the eyes of Solomon Northrup, who wrote his memoir in 1853. He is a free man, treated like an animal, stripped of his clothing, of his very name. He must hide that he is literate and when he reveals his intelligence and superior knowledge, he pays for it.

Movies are about emotion. In the well-made ones, we are caught up in the feelings of the characters. We are so close to them, we catch their every glance, every sharp intake of breath, every hard swallow. We merge with them. This is the power and danger of film.

In the early 1960s, I saw a perfect print of The Birth of a Nation at the old New Yorker in Manhattan. A pianist at the front of the house played the original 1915 score. I remember walking out onto Broadway afterwards, thinking that this was a very great film and also completely repugnant. I haven’t seen it since, but some of it has stayed with me for over 50 years: the great battle sequences, the homecoming of the Little Colonel, the Klan riding to the rescue, looking vaguely like medieval knights. At the end, Lillian Gish and the actor playing the Little Colonel sit on a bluff above the sea. They, the gentle waves, and the hills beyond are all in perfect focus. Sublime.

“The Birth of a Nation” was the first movie shown in the White House. Its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan led to the Klan’s resurgence, this time far beyond the Southern states. I’ve read that Quentin Tarantino thinks of “Django Unchained” as a rebuttal to D. W. Griffith’s masterpiece, but no. Steve McQueen is the one who has done that and more. McQueen is a Brit of Grenadian descent, who lives in Amsterdam and wondered why the entire world knew about Anne Frank, but not Simon Northrup.

I won’t be around to remember the film in 50 years, but for the next few I will remember the way McQueen trusted his audience. Trusted that his audience would pay close attention to what’s happening in the background, slightly out of focus. There you see the studious inattention of slaves to the cruelty taking place in the foreground. To save themselves, they lose themselves. Trusted his audience to see how slavery affected the masters. Treating other human beings as chattel requires self-deception and encourages the ugliest of behaviors.

In Griffth’s movie, Negroes were played by whites in obvious blackface. In “12 Years A Slave,” Chiwetel Ejiofor’s strong face fills the screen and we are moved by his struggle to stay alive and to keep some of his soul intact until he is free again. We are moved by other slaves as well, especially those whose strength and beauty is more than a white master can stand.

At the end of the matinee screening downtown, the sound in the theater was of moviegoers who had not come prepared to cry and were reduced to sniffing as they wiped their faces with their hands. They stayed in the dark to compose themselves, while the credits ran.

Responses to “160 Years Later: 12 Years a Slave”