Unlike “conversation” with its connotation of polite give and take, I always thought of “dialogue” as dueling monologues. An understandable mistake. It’s easy to hear “duologue,” a word that means a play written for two actors. Dialogue, as David Bohm writes, he of theoretical physics and philosophy fame, is from the Greek, meaning “through words.” It’s a “stream of meaning flowing among and through us and between us.” A “flow of meaning in the whole group” that “holds people and societies together.” It’s not like “discussion,” Bohm wrote, which has the same roots as “concussion” and “percussion.” It’s people moving words around together to build a collective view of things, not “playing a game against each other but with each other.”

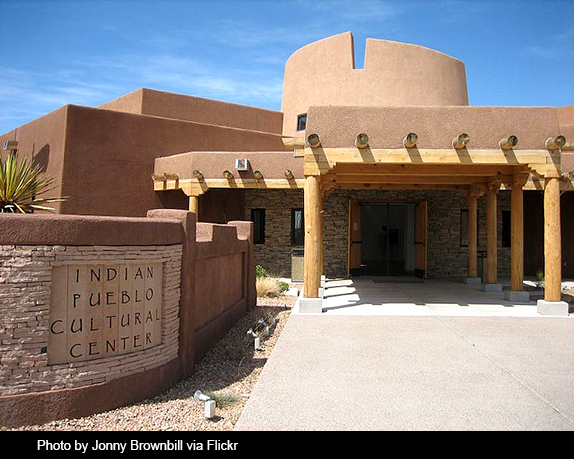

With all those “stream” and “flow” metaphors that Bohm likes to use, the phrase “Water Dialogue” seems redundant. Yet that is the name of the New Mexico group that met on January 9th for their 20th annual statewide meeting, this one at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque. An earlier event that I wrote about for the Mercury, the kickoff meeting for the new regional water plans, drew me to the title of this year's gathering, “Implementing Change: Where’s the Political Will?” since that’s exactly the feeling I had as I left the earlier gathering.

Right from the beginning it felt like Bohm’s ghost inhabited the premises. Another Bohm fan, Lucy Moore, started us off and carried us through the day as moderator. She’s the author of Common Ground on Hostile Turf: Stories from an Environmental Mediator. She is also a co-founder of the Water Dialogue group. Jason John, President of the Board of Directors, who runs the Navajo Nation Water Management Branch in his day job, welcomed us. His words emphasized a history of Water Dialogue meetings aiming for the same things – planning and cooperation.  And then John Leeper, former Navajo Nation Water Management Branch manager, opened with a keynote that featured the story of a water shortage sharing agreement with the title, “Is There Political Will to Avoid Train Wrecks?” He then picked up his guitar and sang an original composition about the drought blues. There were some technical problems when he discovered that he'd left some of the lyrics in his car, but it set the theme of the day much better than any PowerPoint could have.

And then John Leeper, former Navajo Nation Water Management Branch manager, opened with a keynote that featured the story of a water shortage sharing agreement with the title, “Is There Political Will to Avoid Train Wrecks?” He then picked up his guitar and sang an original composition about the drought blues. There were some technical problems when he discovered that he'd left some of the lyrics in his car, but it set the theme of the day much better than any PowerPoint could have.

“Shortage sharing” and how to make it work stood out as a major theme of the day. Here is a simplified version of the concept. New Mexico water rights are based on “prior appropriation.” If my rights are older than your rights and there’s not enough water, I get all of my water and you get what’s left, if there is any. In other words, you’re out of luck. It’s a pretty safe bet that, with increasing population over the years and with the water future looking grim, so-called “priority calls” are going to happen. A couple already have in cases that I won’t go into here. The New York Times, writing of one recent case, called it the “nuclear option in the world of water.”

Shortage sharing is a strategy to avoid priority calls. It works by engaging water users who share a common water resource. In the jargon, it takes a common-pool resource and nudges its human users towards a hybrid of private property and a common property regime. In English, it means you get everyone together who use the same water and they work out a way to share the pain in a fair way if and when there’s not enough water to go around. In other words, they use words to create a new way to think about water among a group tied together by their common use of it. Just like Bohm said a dialogue is supposed to work.

I don’t know about the old water hands in the group, but the strategy sounded fairly high on the sanity scale to me. Several examples were presented to show how the concept has worked in living color. The subtext of the success stories was cautionary, though, as in how “painful”—the word used more than once—the process of working out the agreements had been, how “implementing” them was still underway, and the mixed emotions felt by participants around “lawyers,” who—as men and women used to say of each other in my youth—you can’t get along with them, can’t get along without them. Clearly shortage sharing plans are not fast food. Apparently—there are several dates involved—one of the agreements started officially in 1996 and it’s not wrapped up quite yet.

It would be an interesting and useful bit of research to look at case details and compare them, with each other and with cases that went to court, to learn from shortage sharing experiences so far how to make them easier. It’s the kind of research I’d like to do myself. Maybe I’ll try it after a few thousand more feet of elevation on the water learning curve.

So shortage sharing isn’t arrival in the promised land for water governance, but it is on the road to it. It still leaves out, as many who attended the Water Dialogue pointed out, numerous other pieces of the future water puzzle. It doesn’t talk about how those humans might agree to use less water before the shortage hits. It doesn’t foreground the plants and animals who use the water as well. One exception: Beth Bardwell of the Audubon Society described a sharing plan she helped develop that included both farmers and birds in the lower Rio Grande.

But sharing through dialogue was clearly a concept whose time had come. And it is clearly a concept that should play a role in a sane water future for the state. In fact, Representative Mimi Stewart, a New Mexico legislator, challenged the Water Dialogue in the closing panel. She pointed out that the group represented the many different water interests in the state and showed through their comments during the day their ability to live up to their name, to dialogue in spite of their differences with cooperation in sight. So, she asked, why didn’t they become the political will that the meeting itself called for?

In fact, attendees included elected and appointed water people or their staff, national to local, as well as many kinds of water users and managers. Several faces I recognized had also been part of the regional planning conference I’d attended in December. One closing comment pointed out that no one had mentioned that new state planning process during the entire day and that this disconnect was well south of crazy. I agreed, slapping my forehead in disbelief that two such significant events had no official connection and that I’d accepted that mental ghettoization of water efforts in my own mind as well.

Water dialogue is exactly what we need right now, and not dialogue segregated by conference, but a coming together of ideas generated in many venues. It would be interesting for this group to make a list of categories of water people—such lists appear in most reports I’ve looked at—including some who speak for the plants and animals and the water itself. Then carefully pick a small number who represent the list, a group with time to schmooze and get to know each other, people with experience and an ability to talk across differences with a cooperative attitude who also share a belief that a new system of water governance is essential. Give them six months and a listserv and schedule a gathering every month in a nice place with good food and an open bar. Tell them you’d like to see a draft of a state water plan at the end and otherwise leave them alone. It would be an inexpensive experiment. Even if it failed, it would teach New Mexico a lot about what the problems are and what needs to be done in a comprehensive and coherent way. The legislature could fund it with a small amount of money right now while they’re in Santa Fe. That would be a great birthday present for the New Mexico Water Dialogue’s 20th birthday.

January 15, 2014