Hundreds of refugees from Africa dying as they attempt to cross into Italy, Spain and other parts of southern Europe. Tens of thousands of displaced Syrians searching for safety. Kids fleeing the violence in Central America and ending up in detention centers in places like Dilley, Texas.

The dominant issue of our times will be the movement of people. Not voluntary movement as we know it but movement that is forced, desperate and dangerous. No country knows how to deal with it.

We were just in Spain and saw the aftermath of their financial crisis—an African man selling little packets of Kleenex at a stoplight in Granada; another offering dark glasses and cheap looking CDs at an outdoor restaurant at Sanlúcar de Barrameda. They had decent work before Spain’s economic crisis. How are they going to survive now?

Driving towards Málaga, Moroccan men and women are in the fields, planting crops by hand. Where do they live and how do they get by?

When the economy was booming these immigrants were welcome. Just as in the United States, they were doing work that Spaniards no longer wanted to do.

Here the immigration debate is completely stalled even though it could be a winning situation for all. Republicans could begin to rebuild their image among Hispanics in preparation for the 2016 elections. Immigrants who have overstayed their visas could find a way to “come out of the dark” and do even more than they already do to benefit our economy. American farmers could have a reliable source of labor while their Mexican farm workers would have more money to send home, thus further stabilizing Mexico in the process. American high tech companies could meet their need for the kinds of highly skilled workers who are not available here and, in the process, bring in entrepreneurs who will found new companies and develop new technologies.

The world is opening up in terms of technologies that help us communicate with each other. Unfortunately, it’s closing down in regard to our willingness to learn about, understand and come to know people of different cultures, whether they be cultures in other countries or here at home. While the overt barriers between us are gone, more subtle ones have taken their place. I served in the Army in North Carolina in the early sixties and later worked there in the summer of 1965 in the civil rights movement. The signs of segregation were everywhere then—Friday night KKK rallies in places like Oxford, North Carolina where whole families would sit in the grass with their picnics while the Grand Dragon ranted about blacks and then set the crosses on fire; segregated bathrooms labelled “White” and “Colored;” segregated courtrooms where whites were to sit on one side and blacks on the other.

Those overt and then-legal symbols are long gone but something more insidious is taking place—a process whereby we Americans are becoming more and more isolated not just from other races and cultures but from anyone who doesn’t believe precisely the way we do. Part of it is that “news” has been replaced by advocacy journalism where everything has a particular spin and no one knows where to turn to get the simple facts. Part of it is the bitterness between the two political parties, something that simply didn’t exist when I was in the Colorado House of Representatives in the 1970s. Some of it is economic uncertainty.

On a personal level, when I write about conditions on the Mexican border, I often get the most vicious responses. Here is a direct quote from a recent e-mail. “Stop with the propaganda your only making yourself look like a dumbf---k.the whole WORLD has seen multiple videos of drug gangs with machine guns and drugs crossing the border.”

There’s little that we as individuals can do about Syrian refugees or the immigration problem in southern Europe but, as New Mexicans, we can certainly take a closer look at the people living just across our border and recognize a basic humanity there that deserves our respect. For that reason, I’ve written short profiles of several of the people I’ve come to know there in the hope that this will provide a more humane viewpoint.

First, Hugo Maldonado who lives in a shack about six miles south of the Santa Teresa border crossing just west of Juárez and El Paso . He frequently goes out on foot to collect aluminum cans to resell. I’ve seen him along the highway four times and given him rides home. Often he will walk as much as fifteen or twenty miles to get $4-5 worth of cans.

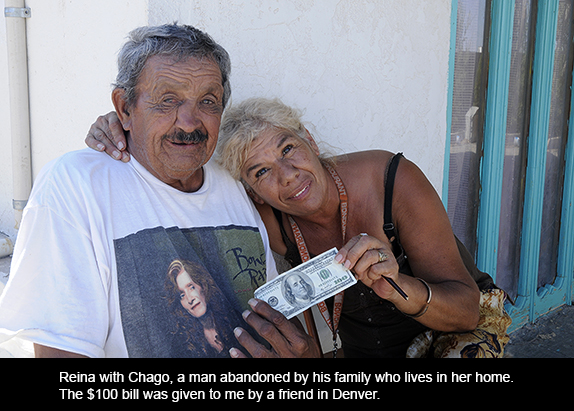

Reina Cisneros lives in Palomas, Mexico. When she steps out her front door, the first thing she sees is the huge border wall that separates our two countries. Despite her own poverty, she cares for older people who have been abandoned by their families as well as visiting other sick people in the Palomas area. Several family members live with her including Bethzaida, one of her granddaughters. Only nine years old, she not only recites but makes up poetry.

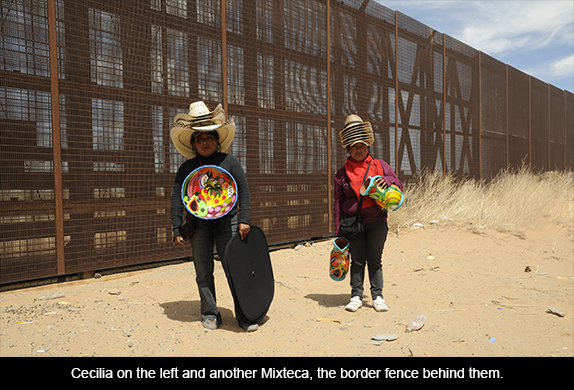

Cecilia Vasquez is a Mixteca Indian originally from the mountain area of the very poor state of Oaxaca. She and her family migrated to Juárez and she spends her days selling trinkets at the Santa Teresa border crossing, along with other members of her tribe. In summer, it is brutally hot and in the winter there is always a sharp, cutting wind. More important, I have rarely ever seen anyone buy anything from her or the thirty or so other Mixtecas there, even though hundreds of cars go through this checkpoint to the US every day.

These three typify what I see along the border—hard working people struggling to survive in the harshest circumstances. What matters is not their race, their color or their nationality but their value as human beings. I wish that we as Americans would make more of an effort to see that.

Responses to “The Movement of People”