This is the first of two columns on a Yucatán journey.

On a warm, bright morning, with high white clouds scudding over the dense tropical forest, four Frenchmen, four Germans, a Dutch couple, an American couple and three Mayas, jabbering in half a dozen languages, including Spanish and Yucatec, puttered slowly down a canal dug 1,500 years ago by residents of the Mayan city of Muyil.

For centuries their descendants stubbornly fought off the Spanish and Mexican governments with the result that the canal is still there and so are the Maya, as well as the magnificent ruins of their old city. Soaring above the jungle panoply, it is a victory over time and endless tribulations.

Such victories are not easy to come by in Mexico, which today, with little attention from the outside world, is undergoing one of its most trying periods.

• Low prices for the country’s main export, oil, threaten to devastate the economy as oil income declined by 50 percent in three months.

• The, until recently, high-riding and popular, President Enrique Peña Nieto is engulfed in a bribery scandal. His wife acquired a $7 million dollar mansion thanks to a guy who owns the company that, without bidding, acquired a contract to build the country’s biggest project in history, a $40 billion, 200-mile high speed railroad in central Mexico. The treasury secretary did pretty much the same thing as his president.

• The Army executed in cold blood 22 prisoners who had already surrendered, then lied about it.

• And worst of all, the government has made pathetically little progress in solving the disappearance and presumed murder of 43 student-teachers at the hands of a cabal of narcoterrorists, police and government officials. Several low-ranking drug dealers have been arrested, and a mayor and his wife are under house arrest.

The case of the students, which occurred in August, is uniting the country in perpetual nationwide demonstrations by tens of thousands. The head of the Human Rights Commission has publicly challenged the president to his face. A Mexican student interrupted the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo to call attention to the scandal. All in all, it is unlike anything Mexico has seen since at least 1968.

During a recent visit to Mexico, all of this turmoil usually seemed a long way from the tranquil beaches, forests and villages of Quintana Roo, the newest Mexican state, which occupies a narrow, 100-mile-long strip along Yucatán’s Caribbean coast. This is where my wife and I spent 12 halcyon days exploring Sian Ka’an, Mexico’s second largest natural preserve, Laguna Bacalar, its second largest fresh water lake (technically a lagoon), ancient Mayan cenotes (caves filled with fresh water), remote villages and some of the most impressive ancient Maya ruins.

The turmoil in the rest of Mexico is just starting to impinge on Quintana Roo in peripheral ways—small demonstrations on behalf of the students, two recent assassinations in the resort city of Playa del Carmen, a new sense of fearfulness among residents of Chetumal, the state’s small capital on the southern border with Belize. But overall, the Yucatán peninsula remains distant, both physically and psychologically, from the pressures and tensions that are disrupting life elsewhere.

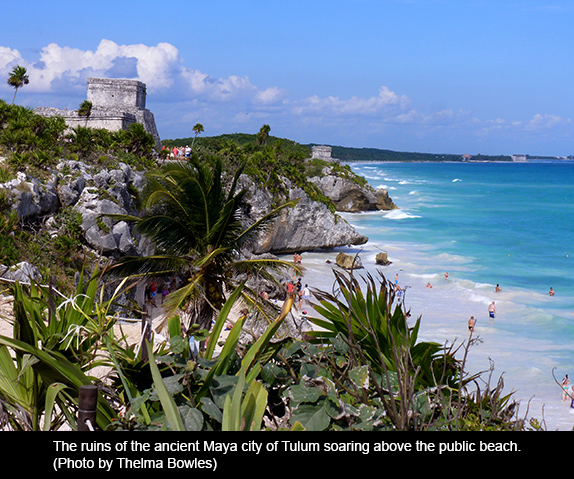

Although I had been to Yucatán twice before—in the 1960s and 1970s—I found surprises. One was a new network of well paved highways and the nearly complete electrical power grid (except, ironically, on the resort-studded coast). Another was the almost total absence of Americans outside the major resorts. Traveling by bus to famous sites, splendid natural areas and impressive ruins, we saw almost no Americans. Instead, what we found was a babel of languages and cultures. Europeans, Asians and even Colombians and Brazilians were in evidence, while Americans seemed content to sun themselves on outdoor beds on the beaches of their hotels. Even the beautiful Caribbean was nearly empty of swimmers—until we swam in the public beach adjacent to the Mayan ruin of Tulum, accompanied by a throng of locals and travelers staying in relatively cheap hostels in town.

The beach is indeed beautiful, every bit as spectacular as the tourist brochures suggest. A German magazine recently did a cover story describing the beaches of Tulum, which was our base on this trip, as the most beautiful in the world, helping to lure Germans to the area. I have seen fine beaches in many parts of the world, but as far as I am concerned, the description may well be true.

The sands are pure white and of the finest, softest powder. The sea is transparent, tranquil, turquoise water over a smooth sandy bottom, shading into royal blue at greater depths all the way out to the off-shore reef that protects nearly the entire Caribbean shore of Yucatán, Belize and Honduras from the surf of the open sea.

The reef is supposed to be one of the great attractions of this area, but a number of divers reported to us it was virtually dead, killed off by development, cruise ships and hurricanes. On an earlier trip, we had relished the splendid part of the reef that still lives off the coast of Belize and decided to pass it up this time. Efforts are being made to revive the reef—by transplanting live coral from elsewhere— especially in Xcilak, a remote village from which it is possible to wade all the way out to the reef.

We found Tulum to be a surprise in many ways. For many years, travelers had raved to us about the beauty of this inexpensive, out-of-the-way, laid-back hippy village. Today, it is none of these things. The small village has doubled in population in half a dozen years and is now a substantial little town with a lively and diverse group of small hotels, restaurants and shops. To my surprise, although it has lost its former cachet, it is actually quite a pleasant place where you can still get a good $2 meal or a terrific room with breakfast and a very useful bicycle for $40 to $50—less than half the cheapest resorts on the coast a couple of miles away.

The 10-mile long coastal strip of Tulum is a bizarre place. Except for the gorgeous beaches on federal property adjacent to the Tulum ruins, there are no public beaches. Expensive hotels, most of them calling themselves “eco” something or “yoga” something, with salons, spas and massages, line the beach side of the narrow road, crowded with crawling traffic, bicyclists and pedestrians. On the inland side, expensive restaurants and clubs fill most of the lots.

Adding to the strangeness, there is no power grid here, no water and sewer systems, no lights. The only electricity comes from private generators. Expensive rooms and dinner tables are lit only by candles, romantic or inconvenient depending on one’s point of view.

We found one, and only one, inexpensive place near the beach. It was called Turquesa. There, we slept in large permanent tents on a real queen-sized bed. A continental breakfast and cold outdoor showers were included. These tents cost the same as a very comfortable room in town with hot water and lights. Moreover, Turquesa is across the street from the beach, requiring us to bluff our way past one of the resort reception desks to take a swim. Once on the beach, however, the magnificent scene was all ours for miles north and south.

The town of Tulum is the heart of a delightful sandwich, with the seaside ruins on its northern edge and the vast Sian Ka’an preserve—which includes dense jungles, Maya ruins, two huge lagoons, mangrove swamps, noted bird-watching islands and the Mayan canal—bordering it to the south. In addition, just inland are a series of cenotes, the largest of which, Gran Cenote, extends underground for something like 100 miles. We met many European divers who had come to Yucatán with the sole purpose of exploring the cenotes, which requires an especially high level of dive certificate.

A bit further inland are the ruins of Cobá, one of the largest and greatest cities of the ancient Maya world. We climbed hundreds of steep steps to the top of its main pyramid, the second tallest in the Maya world. From there, the view extends for dozens of miles over the unbroken, low-lying forest of Yucatán, seemingly unaltered during thousands of years of human habitation. From there, not a single resort, no matter how tall and prepossessing, nor a single cruise ship, no matter how big and tourist-packed, is visible. Only the 70,000 square miles of jungle that for a thousand years was the heartland of the western hemisphere’s greatest civilization.

January 26, 2015