Editor's note: Mike Agar is speaking at the School for American Research in Santa Fe at noon on Sept. 17th on A Game of Scientific Clue: It was the human in the anthropocene with the water.

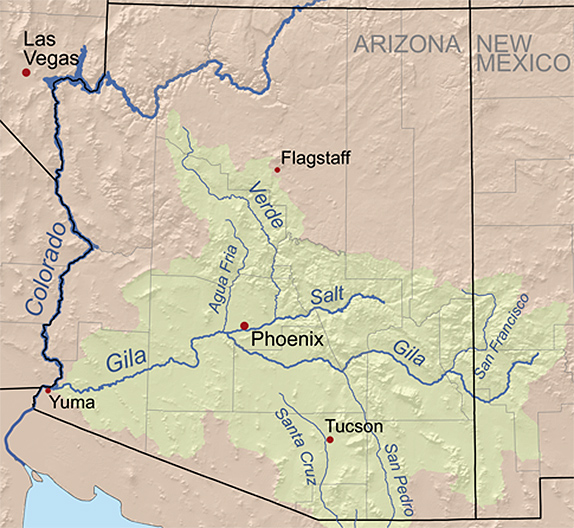

On August 26th, the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission (ISC) met at the Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque. Avanyu, the Tewa water deity, must have chuckled at the historical irony. The Commission is in charge of the waters that New Mexico shares with other states. The daylong session flooded – pun intended – those present with detailed information about the New Mexican part of the Gila River Basin. We, the public, were effectively brought into the complexity of the decision that the Commissioners must make by the end of the year. I don’t envy them the job.

The Commission was forced into the decision some time ago—any water story in the state begins with “some time ago.” Congress passed a law to settle up an interstate water issue with Arizona. (This was back in the days when Congress actually did pass laws.) The Arizona Water Settlements Act of 2004, or AWSA, gave the four New Mexico counties in the basin new rights to 14,000 acre-feet of water and up to $128 million in federal funding for “diversion” projects—i.e. ways for humans to take that new water and use it. By the end of 2014, the state is required to let the Secretary of the Interior know how it wants to spend the money. There are roughly a baker’s dozen proposals on the table, depending on how you count them.

In her recent extensive article in the Santa Fe Reporter, Laura Paskus lays out the history, many of the hot issues, and some stories from a recent meeting with the public. There are many chips on the table here. Trying to make sense of everything at the August ISC meeting all at once was like a view through a kaleidoscope built with broken mirrors. Further complicating the matter, the meeting discourse kept sliding into “diversion” versus “conservation,” a forced choice in 20th century environmental politics that in my view often blocks innovation as we slipslide into the uncharted territory of the anthropocene.

I tried to write an article about the entire meeting. I gave up after several drafts. It would require a book. One specific thing was clear to me, though, speaking of the anthropocene. The meeting at the Pueblo Center poured out data from hydrology, engineering, biology and economics. But, in spite of terms like “stakeholder” and “community” and “public participation” that were tossed around like beach balls, there wasn’t a shred of any real social science. Very little about who people in the Gila basin are, how they live, or what consequences any of the proposed projects might have on their lives.

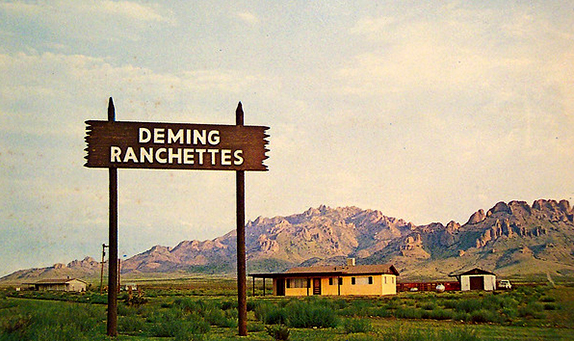

Commission staff did show a few slides of “stakeholder input,” a list of sound bites that showed variety and contradictions in one-line opinion statements. A few other slides showed demographics of towns where projects were proposed. Residents, on average, were lower on resources than New Mexico averages. How do new water rights and cash look from their angle of vision? The Deming Headlight newspaper ran a feature a year ago, “NM voters oppose Gila River Diversion,” based on a poll by a Republican polling firm. Did that editorial choice reflect local sentiment? Of which residents? Who knows. The slides and statistics were a high altitude ride at the speed of sound over complicated social terrain without comment on what they meant for the shape a decision should take.

It was obvious that the staff at the Albuquerque meeting knew much more about the region than time or structure allowed them to say. But really, this is terrible social science. Nothing personal. If I claimed to do hydrology or engineering it would be even more embarrassing. The point is, fine a job as state and federal staff did presenting the technical project proposals, there wasn’t any systematic research on the people involved, neither the ones making the decision nor the ones about whom it was being made. There was almost nothing on who the social and political and economic actors in the basin are, what kind of world they live in, or how their relationship to water is grounded in biography and history. As evaluations of recent stakeholder-oriented water management show over and over again, projects that ignore the local human and social context don’t work well, if they work at all. If an outsider wants to know the context, he or she must go out and learn it from the point of view of those real people who live it day to day. Then translations and adaptations back and forth between distant political and technical expertise and local reality stand a chance of becoming mutually coherent.

Failing that kind of research effort, maybe the experts and the locals could at least have a meeting? Apparently, they tried and failed. In the Commission’s own summary:

In September 2007, the Southwest New Mexico Stakeholders Group (“SWNMSG”) was formed to reach a consensus among stakeholders on projects using AWSA water and/or funds. After several years of work, the SWNMSG could not reach consensus on a small number of projects.

What happened? Was help of the sort that professional environmental mediator Luci Moore describes in her book, Common Ground on Hostile Turf, included? What conflicts came up and flattened that social learning curve as it tried to climb out of conflict into consensus? Nothing was said about the history of SWNMSG, though with an acronym like that they were probably doomed from the start. “I’ll be late, dear, I’m going to the swunmusug meeting.” Laura Paskus’ article, mentioned above, tells the story of one community meeting in Cliff. The description suggests the problem. It wasn’t a community meeting. It was state and federal staff giving an audience technical details about the proposals and then not being able to answer the questions that “the community” asked because the answers weren’t part of their job description. Kind of like the computer guy telling you details of 64 bit architecture when you want to know if the new chip will still run Facebook.

The main glimpse into the world of the Gila at the meeting were the four presentations by “stakeholder group representatives,” limited to ten minutes each. This still wasn’t social science, but it was the closest to the kind of data required to start doing it. The four dealt with—in this order, using the agenda descriptions—1) recreational and cultural impact, 2) conservation alternatives, 3) farmers’ and ranchers’ perspective, and 4) impacts to Luna County. The four presentations sketched the real worlds of people/water connections in the basin from each of the presenters’ points of view. There were also a few volunteered “public presentations” at the end of the day, but at three minutes each they were more of a speed-dating kind of thing. The people were the right ones to speak, though, and did their best, and once the Commission heard the first few they made room for more and asked for written statements. Some interest in actual stakeholder voices was clearly there.

If real research in pursuit of basin management strategies was possible, those four stakeholder representatives and the three minute volunteers would be a great place to begin with interviews and more extensive visits to their worlds. It’s called “action research” in the jargon, among other things. It’s also similar to the “user experience” research boom in the private sector as well I know of a nonprofit in Santa Fe, a social research consulting firm in Albuquerque, and faculty at UNM who could do this kind of work.

Listening to the four stakeholder representatives from the basin, I heard the theme that water is very, very personal in New Mexico, for different reasons for different people to be sure, but personal in a “who I am" kind of way. I’m not talking about stereotypic economic actors here, rationally calculating monetary outcomes in isolation with perfect information. I mean actual, living people who, for their different reasons, experience the river as a core part of who they are. This profound connection might explain why consensus is so difficult to achieve. It might need to be the focus of conversations, as if not more important than the economic arguments that many feel are the only valid way to express what is of personal and social importance.

None of the four stakeholders were out to destroy the wilderness for money. There were no Santa Fe Ring type capitalist villains among them. “Capitalism” was represented by a local rancher, a county politician worried about his constituents, a guide whose passion was educating the urban to appreciate the wild, and a local association arguing to use water more wisely. In her article, Paskus mentioned extensive land ownership by the mining industry in the region. Given that industry’s recent behavior over the copper mining rules, I’d want to know more about what they were thinking about all this, but no one spoke of their interests at the meeting.

The four stakeholders didn’t represent big money. Their differences were around how much water you could take out without hurting the river and what you should do with it. All four agreed that the cost to build the big diversion was high, maybe even insane—it is now estimated at about 800 million. They disagreed on whether it was worth it or not. Nobody at all spoke in detail about how project construction and operation would be paid for or how much the new water would cost per acre-foot. The rancher and county commissioner emphasized that the state needed to grab the 14,000 acre feet or New Mexico would lose it. The conservation and culture/recreation spokespersons argued that reducing the flow would push the Gila towards being just another managed ditch. No one that I heard—stakeholder, expert, or Commissioner—considered in any detail what climate change might turn the river into in the long term and how the decision could anticipate that scenario.

I wondered, naively, I’m the first to admit, if there wasn’t some space for discussion among the four of them—among the basin people, not among the government experts and consulting firms. New ideas might have taken shape if there had been some action research to clarify local interests and social connections together with the kind of mediation that Luci Moore represents. Couldn’t there have been a way to explore that solution space—preserve the wilderness (there are already some diversions), put the new water rights to good use, keep the costs reasonable with respect to the benefits, and conserve in towns and on ranches? Isn’t there a way that people from the basin might have talked this over, with experts as resources to be sure, but as resources who listen and learn before they advise?

Good action research functions like good family therapy or good organizational development. It takes a situation where people know they have a problem but are so bound up with longstanding emotionally loaded habits that they can’t see clearly. The job of the professional action researcher is to come in, mostly listen and learn, and then create a framework that wasn’t visible before, a framework where a different kind of conversation might start. It doesn’t always work, and it’s hardly ever easy, but it has worked often enough to make it worth a try.

With any luck efforts like that could provide alternatives to the lengthy, expensive, inconclusive dramas that New Mexico water governance so often lands in. Too late for the Gila now—the Commissioners have to decide by the end of the year. But maybe the next big water question? It’s not a complete fantasy. There are glimmers of an alternative in recent water shortage sharing agreements in the state and projects around the world involving stakeholder-oriented water management are on the upswing. One way or another, the state model for stakeholder/community/public participation needs an upgrade. There are many frameworks and examples available to guide the change. Nothing stands in the way of the experiment but a lack of political will on the part of those with the power and resources to enable it.

(Photos: Avanyu mural by Fabrice Florin; Gila map by kmusser; Deming postcard by Dave)

September 16, 2014