(Banana flower, Hanoi. Images by Margaret Randall)

(Banana flower, Hanoi. Images by Margaret Randall)

The American War in Vietnam (what the Vietnamese call it) is today pretty uniformly acknowledged as a mistake at best, a travesty at worst. Never before or since, in the history of US bellicosity, did opposition rise to such a fever pitch that it made ending our involvement an imperative. Tens of thousands of potential recruits and soldiers fled to Canada or Sweden to avoid fighting. The war led to the impeachment of a president. When Daniel Elsberg released The Pentagon Papers, proving that the American public had been massively misled, major newspapers defied government orders and ran the documents in their entirety. Anti-war marches and rallies routinely numbered over a million.

(Fowl market)

(Fowl market)

Vietnam veterans came home to an angry nation, a nation that felt betrayed. People often took their anger and frustration out on soldiers who had already suffered more than their share. The Vietnam War Memorial, Maya Lin’s extraordinary monument in Washington DC, helped heal the wounds of a war that should never have been. But the lessons of Vietnam were never learned by successive US administrations, and they have embroiled us in other equally ill-conceived wars.

Vietnam was the issue that defined my generation. I came of age as young men I knew struggled with the decision of whether or not to evade the draft. Later, other men my age, who fought and returned, endured lifetimes of PTSD—a prelude to what is happening again today. For someone like myself, for whom working for social change has been important, Vietnam has remained a vital example of well-organized protest winning its objective. Never, since that war, have we been able to stop what we consider to be tragic government policy.

What stays with me about Vietnam, though, is how I ceased seeing it as a war and began to experience it as a nation: of complex people who lived and died and in between farmed, became doctors and artists, wrote poetry, cooked amazing foods, produced exceptional leaders, and stood up to the greatest military power on earth and defeated it. I was extraordinarily fortunate. I was able to travel to North Vietnam in 1974, just six months before the war ended and the country was reunited. And many years later I was able to return.

(Woman worker at ceramics factory)

(Woman worker at ceramics factory)

That first trip marked my life in ways I will never forget. I lived in Cuba, at the time. Cuba supported the Vietnamese people’s quest for independence, and Vietnam had a strong presence there. Hundreds of Vietnamese young people studied free at Cuban universities; the young women’s simple white shirts, dark trousers, and long black braids were a common sight on Havana’s streets. They vowed not to cut their hair until their country was free. Radio Havana Cuba gave the Vietnamese 20-minute segments, repeated several times a day, through which they could use shortwave to speak to the American people about the war.

The head of The Voice of Vietnam in Cuba studied English with me. His name was Phuc, but we called him Fernando. For several years I would visit his apartment three times a week. He said he’d chosen me because my English seemed ordinary, what he perceived as closest to street English of anyone around. His stories about his country enabled me to feel I knew it a little.

I had begun doing oral history with women, mostly Cuban women to that point. And it was because of my oral history work that the North Vietnamese Women’s Union invited me to visit their country; they wanted me to talk to their heroic women and perhaps produce a book of their stories.

(Hanoi, Old woman and young boy)

(Hanoi, Old woman and young boy)

This is how I came to travel to that country, off-limits to most in my own. The several months I spent there were life-changing. I flew into Hanoi, and was met by members of the Union. Each wore a plain white headband that I soon learned signaled what a black armband denotes here: she had lost someone close. Loss was everywhere. It was, after all, a nation at war. But the first thing that struck me was that it was not only a nation at war, but a nation where people continued to live their lives, marry, have children, attend the theater, and research ways of confronting the ravages of chemical and biological warfare.

Hanoi was a beautiful city, built around lakes. I remember the individual bomb shelters, little holes in the pavement where people dropped when the sirens went off. They pulled metal disks, like the manhole covers in Manhattan, over themselves and waited. When the all-clear sounded, they emerged to resume their daily activities. I visited a hospital where children burned by napalm were being treated. I was astonished when I was taken to a ward where several patients who had undergone sex-change operations were recovering. This was, after all, 1974.

(Hanoi, Temple of Literature doors)

I discovered I was one of nine foreigners in North Vietnam at the time. Tourism doesn’t mix with war. Traveling down Highway One, from Hanoi to the 17th parallel where the country had arbitrarily been divided, almost every bridge was bombed out. Pontoon barges carried people across until villagers were able to rebuild the bridge, which was soon destroyed again. I remember standing on one of those pontoon barges and hearing a woman ask my guide where I was from. When my guide spoke the word for American, I saw a fleeting second of the purest hate I had ever seen in another’s eyes. Immediately the woman recomposed herself and smiled. “Welcome to Vietnam,” she said.

(Hanoi street scene)

(Hanoi street scene)

South of the 17th parallel, in the then liberated area called Quang-Tri, I spent a few days at the headquarters of the South Vietnamese provisional revolutionary government. The woman who received us was that provisional government’s minister of public health. She was lovely and very gracious. I was shocked to learn that just that day she had received news of a son’s death. Like so many, he had died fighting against the invaders. Ho Chi Minh’s famous motto was everywhere: “Nothing is more precious than independence and freedom.”

My hosts told me that one of their most important campaigns was to eradicate polygamy. Union members went from house to house, talking with women and empowering them to demand fairness in their lives.

In Quang Tree I also visited a camp where young women lived, studied, and produced beautiful handiwork. They explained that they were the wives and sisters, daughters and lovers of the guerrilla fighters we called the Vietcong. They told me they sneak into the military camps at night and assured me the war would be over soon. “The people are rising up,” they said, “and we tell our men not to continue to fight. They are moving from village to village without firing their weapons. People are simply coming over to our side.”

“How long?” I asked, highly skeptical. In the western press we had no evidence of the war’s impending end. “About six months,” the women said. How could they be so sure, I wondered. This was September, 1974. It turned out they were right, almost to the day. On April 25, 1975, the war was over.

(Halong Bay)

(Halong Bay)

On that trip I conversed with women in all walks of life: professionals and farmers, students and housewives, scientists and teachers. One group of women who impressed me particularly comprised a small anti-aircraft unit along the country’s vulnerable coast. One of them explained that they’d had to stop their education because of the war. None had gone past third grade. It was difficult for them to master the math necessary to use the complicated artillery with which they brought down the enemy planes. Only necessity and will had enabled them to succeed.

I entered tunnels where people hid by day, even bringing their beloved water buffalo in with them. People lived in those tunnels, studied in them, married and died in them. I was told about a kind of “blindness” many of the children endured, when they finally emerged to sunlight. Many Vietnamese children of that era had vision problems. Others retained a lifelong fear of the color red.

(Chao Doc on the Mekong River)

(Chao Doc on the Mekong River)

Everywhere I went, in the Vietnam of 1974, people wanted to impress upon me the fact that they differentiated between the US government and the American people. We know, they insisted, that if your people knew the truth they would be against the war. When I said how terrible I felt for their sacrifice, they responded that what we were doing was just as important, that we each had a role to play.

I have never forgotten those months, or the people I met. Images, such as the absolutely barren earth of Quang Tri—earth that had been punished by chemical poison for generations into the future—still live in my eyes. But I also hold images of ancient pagodas, of people telling jokes and laughing, of lush landscapes and beautiful art. Until it fell apart on my finger, I wore a ring made from the metal of a downed B-52. It was an act of solidarity. I discovered, in more ways that I can say, that Vietnam was not a war but a country.

(Ho Chi Minh City, Exhibition in War Remnants Museum)

(Ho Chi Minh City, Exhibition in War Remnants Museum)

Almost three decades passed. The US and Vietnam resumed diplomatic and trade relations. Many of those on both sides, who once faced each other as enemies, managed to make some sort of peace with a terrible chapter in their lives. Veterans of both armies took part in reconciliation experiences. These were important not only to the people involved, but for a collective sense of closure. In the US, new generations realized they had been wrong to blame individual soldiers and reevaluated their negative responses to young men who had been caught in the criminal strategies of superiors.

In 1995, retired US General Robert McNamara met with his Vietnamese counterpart, General Nguyen Giap, and come to the conclusion that no Vietnamese gunboats had attacked American destroyers during the so-called Gulf of Tonkin incident of August 1964. It had all been a fabrication on the part of the hawks, those determined to push us into war. The mainstream media supported the lie, and 58,000 US soldiers and two million Vietnamese were made to pay the price.

It’s tragic that by the time the George W. Bush administration produced its “proof of the existence of weapons of mass destruction” in Iraq, memory of what happened in Vietnam had been broken beyond repair.

(China Beach, once site of R & R for US soldiers, now a fishing community)

(China Beach, once site of R & R for US soldiers, now a fishing community)

Twenty-eight years after that initial journey, I wanted to visit Vietnam again. I was curious as to how the Communist country had weathered the implosion of the socialist world, what choices it had made in terms of adapting to international trade while attempting to conserve basic social services. I had long admired Vietnam for going against its closest ally, China, and saving Cambodia from the horrors of the Khmer Rouge. That took a lot of courage, and seemed to me to define real humanist values at a time when defying one of the great powers was costly for a small dependent nation. I wanted to look at a landscape I had last seen pockmarked by war and deeply stressed. I wondered if anyone I had known on that first trip was still alive.

(Hue, Imperial Palace grounds)

Barbara and I traveled with a small group in December 2007. This time we were able to go from Hanoi all the way down to Ho Chi Minh City (now again often called Saigon), stopping in Hue, Hoi An, Halong Bay, and the Mekong Delta. We spent a rainy day near My Son, visiting the 4th to 13th century AD Champa ruins. We stopped at China Beach, once an R & R destination for US soldiers, now a peaceful stretch of sand dotted with round fishing baskets.

(Fourth century AD Champa ruins)

(Fourth century AD Champa ruins)

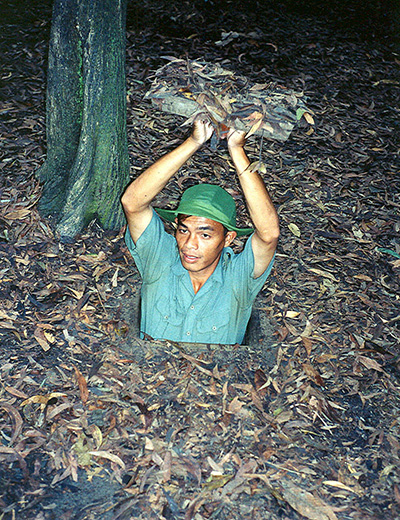

(Cu Chi Tunnels, soldier shows us a camouflaged entrance)

At Cu Chi, we learned about the hundreds of miles of tunnels the Vietcong dug even beneath US army bases in the southern part of the country. We were able to descend into them briefly, to view what had once been kitchens and operating rooms. We marveled at Vietnamese ingenuity in the face of overpowering assault.

In Hanoi we were moved by President Ho Chi Minh’s humble home and his mausoleum. We visited the Hanoi Hilton, actually a prison predating by many years the US war in Vietnam, and wandered the grounds of the beautiful Temple of Literature. We attended a water puppet show.

It was in the capitol as well that I was able to visit the offices of the Union of Vietnamese Women (the organization’s name changed with the country’s reunification). I brought a copy of the little book I had written after my 1974 trip, and a couple of faded photographs of some of the people who had facilitated that first amazing journey. The Union’s secretary of foreign relations received me, and was very forthcoming about the challenges they still face. When she looked at my old photographs she burst into tears. The woman who had been my guide so long before had also been her mentor. Long gone, she somehow brought us together.

(Ho Chi Minh City traffic)

(Ho Chi Minh City traffic)

On this return trip, I discovered that General Giap, nearing 100, was still alive. I had admired him for years, ever since reading a speech he gave to a group of guerrilla fighters, in which he explained that poetry and art are as important as guns. I learned that he was still alert and active, and that his current concerns are global warming and environmental healing.

In Ho Chi Minh City, in the much more westernized southern part of Vietnam, we visited the War Remnants Museum: painful but necessary. Again, responsibility for the war was laid at the feet of a succession of US administrations, not the people they had deceived.

In our group was a US veteran who had completed a tour of duty in Vietnam. We wondered how he would react to visiting a place that must hold complex and distressing emotions. He had been wounded twice, once quite near one of our stops. His wife ranted against what she considered Communist propaganda at Cu Chi. He put his hand on her arm, then, and I heard him say: “Listen, they have their story to tell.” It was clear he had made peace with his past.

(Hanoi, traditional water puppets)

(Hanoi, traditional water puppets)

June 06, 2013