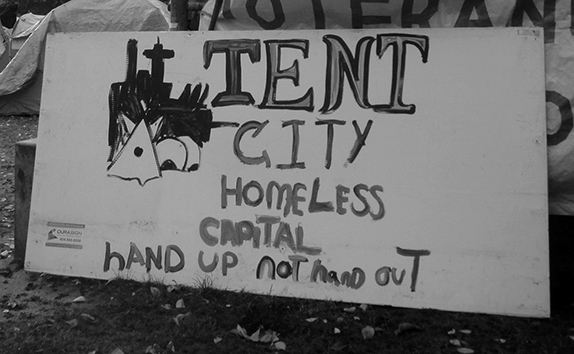

On Monday, the city issued three-day eviction notices to the people living in tents along First Street. The notices are based on nuisance abatement laws, statues allowing the removal of something or someone deemed to cause an inconvenience or annoyance. The posted notices state that the city will file a complaint in Metropolitan Court “to eject you” from the city’s property or right of way. As we know, the strategy of the city’s leaders to eject the nuisances near the Rail Yards will only shuffle Albuquerque’s most-needy population to other locations where these individuals will be less concentrated and less visible.

Realistically, pitching tents on the side of the road will not solve any long term problem, but, for someone in need of shelter, it is temporary relief from the elements and offers a bit of personal space. The tent set-up, however, falls short of standards of human dignity in areas of hygiene, safety and permanence. Over 6,000 people will be homeless in Albuquerque during the next year. In order to make our community a more just place, we must truly consider how the desperately underserved are trying to survive: tired, hungry and uncomfortable.

The underserved in Albuquerque are women and children, the working and unemployed, the abused and addicted, the different and the hard-on-their-luck. When I think of the people pushed to the margins of our community, I think of them facing dangerous temperatures, waiting winter’s long nights out under bridges or finding temporary comfort in a fast-food lobby. I think of some sleeping in their cars while others are between couches or shelters. I see police asking people to stop asking for money at intersections and move along. I see housed people avoid the desperately poor by walking the other direction or ignoring them.

From inside the windows of our homes, we—well-intentioned, compassionate people—hope the people left on the margins will fend for themselves, or we believe some organization will rescue them. This is our privileged strategy for others to survive, not diverging far from our leaders. But the reality is this: with an average age of 48-years-old at death—a lifespan one-third shorter than a housed person’s—people without homes have died at a rate of more than one person per day during the last eight years.

With people without homes in Albuquerque, a city like any its size, maintains a multitude of vacant buildings. These climate-controlled and clean buildings have specialty purposes for which they are opened occasionally. Driving inside our cars, we see churches, small and mega, that sit as empty monuments of worship for the majority of the week. Thousand-seat stadiums, such as The Pit and Tingley Coliseum, cost the public millions of dollars to renovate, but they are without crowds the majority of the year. The vast Convention Center sits Downtown often unused for the next event. And even public spaces that are filled with people regularly, such as schools and community centers, spend hours every day as vacant facilities.

The realization that Albuquerque has millions of maintained square feet of space that are inaccessible to the most needy makes me uncomfortable at best. I hurt to know that people suffer in our community not because of a lack of resources, but because we consistently make choices that exclude the desperately underserved from accessing sources of dignity, health and hygiene.

The arguments against using public spaces to protect the most needy are numerous. The plan will cost public money: professionals will need to be trained and salaried, buildings will need to be updated and maintained. Churchgoers and parents will fret about the inconveniences and discomforts—the nuances—of sharing spaces with the needy. Contracts will be lost when organizations decide not to bring their business to a convention center that doubles as living space. People will cite increases in liability premiums as a prohibitive cost. But, in all cases, these are the exclusionary sentiments keeping the divide among us salient. We can properly care for people, and it begins with a shift in values choosing to protect human dignity before privilege and profit.

Our failures to care for the desperately poor are not just reserved for shelter. Children go hungry during all parts of the year. People need medical support in every month. All humans need clean water daily, and transient shelter comes with uncertainties and dangers that deserve as much attention as a 911 call from a home. Yet again, the city is equipped with the infrastructure to offer everyone dignity, but we must be creative and inclusive in our solutions. APS Food Services make thousands of meals daily, and another round of meals could feed the hungry. Fleets of city buses make rounds through the city, and, with trained staff, designated buses could help transport people to receive the most basic medical and counseling services, and take people to shelters. If there is not enough human labor to support this initiative, interested volunteers could be dismissed from work a couple hours every week to work in inclusive public facilities.

For now, the people will be moved from the First Street curb to less-seen shadows of the city. The out of sight, out of mind strategy will be a temporary relief for city leaders, but the suffering of people in transient lifestyles will continue, as it was before the eviction, as it will be after. And we, the people in our homes, will continue to live in a city where the infrastructure to support every person remains unused. Our problem is an issue of the dominant classes looking out windows rather than opening doors. This vacancy in our morality will remain until we serve the people in need of fundamental care.

(Photo by urbansnaps – kennymc / CC)

February 13, 2015