Under the title, “On the Map: Unfolding Albuquerque Art + Design,” a citywide celebration of Albuquerque’s art scene is underway, providing an occasion to take stock.

“On the Map” is an extensive collaboration, formed in cultural partnership with more than twenty participating organizations, including 516 ARTS, the Harwood Art Center, Richard Levy Gallery, the University Art Museum, the Albuquerque Museum, and the City of Albuquerque Public Art Urban Enhancement Program. Public institutions are being joined by private galleries to present a variety of exhibitions, lectures, performances, and educational programming that will extend through June. A full listing of events can be accessed at www.ABQontheMap.com.

The centerpiece of the celebration is a massive survey exhibition, “Visualizing Albuquerque” at the Albuquerque Museum, which opened at the end of January and runs through May 3. A welcome and long overdue look at artmaking in the middle Rio Grande region, the Museum’s exhibition acknowledges the contribution of Albuquerque’s artists and demonstrates their independence from the more widely known art produced by the Taos and Santa Fe art colonies.

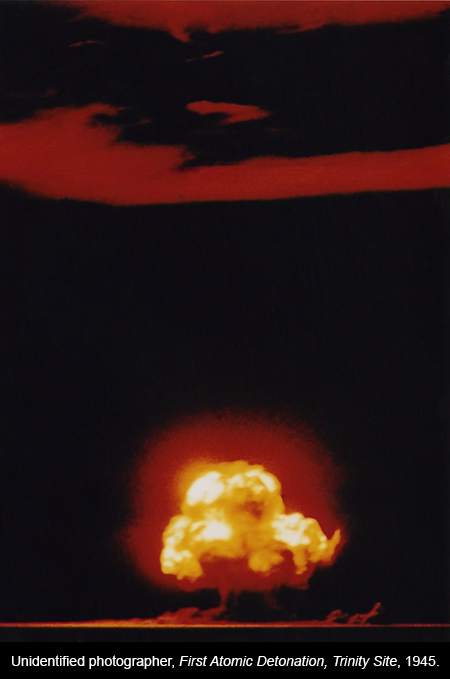

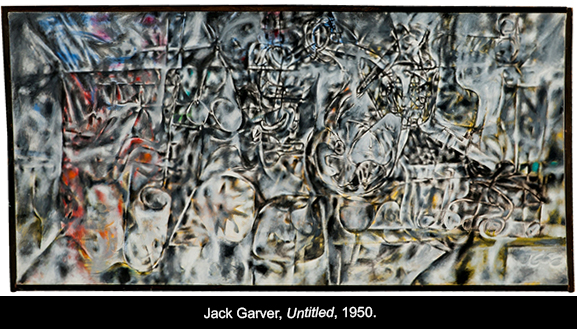

“Albuquerque’s image as a commercial, technological, and military center has overshadowed its simultaneous evolution as a thriving artist community addressing modern concerns with provocative images,” writes Joe Traugott, the exhibition’s guest curator and recently retired curator of twentieth-century art at the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe. “Albuquerque went modern after the detonation of the first atomic weapon at the Trinity Site, and the art of the region followed this modernist track.” To underscore his point, Traugott has placed a big, blown-up color photograph of the Trinity explosion, like a giant Rothko painting, as the exhibition’s opening image. It is paired with a rough and richly exploratory abstract painting by Jack Garver, whose irregular stretcher bars betray the poverty and daring of Albuquerque’s adventurous seekers in the post-war era.

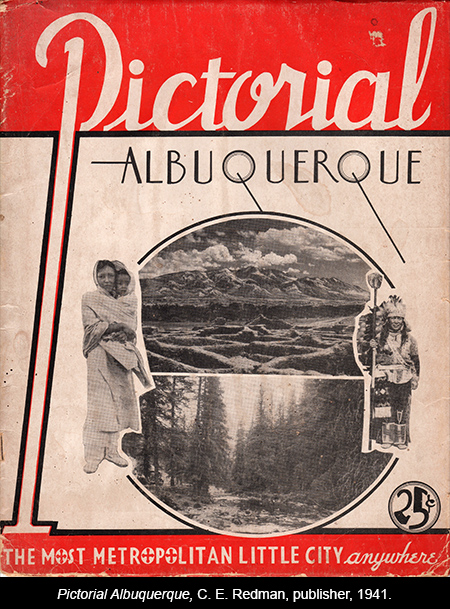

In their foreword to the catalog, the Museum’s director Cathy Wright and curator of art Andrew Connors refer to various pictorial booklets that were produced over the years to promote Albuquerque’s business outlook. One of them, published in 1892, boasts of the city’s banking and distribution industries, its wool and cattle markets, and its potential for lumber, canning and food processing entrepreneurs, while noting its already existing retail leadership, its health-related sanitariums, its churches, its schools, and the presence of a Territorial University. The photographs depict an array of up-to-date brick and stone buildings that might be encountered anywhere in the US—not a single adobe in sight.

“With such a publication in 1892,” the authors note, “it can be seen as nothing more than a historical anachronism that six years later two artists, Bert Phillips and Ernest Blumenschein, ‘discovered’ Taos and began promoting it as a destination for artists.”

I have one of these Chamber-of-Commerce-style booklets from the 1940s, picked up by my parents when they lived in Albuquerque during the Second World War. What’s endearing is the statement running along the bottom of the brochure. Taking pride in the multicultural aspect of the region as well as the multiplicity of the city’s business interests, the caption reads: “The most metropolitan little city anywhere.” Poor Albuquerque; it was not yet cosmopolitan enough for its boosters to realize that cosmopolitan was the word they wanted, not metropolitan. Moreover, in 1941, the city was not yet a metropolis.

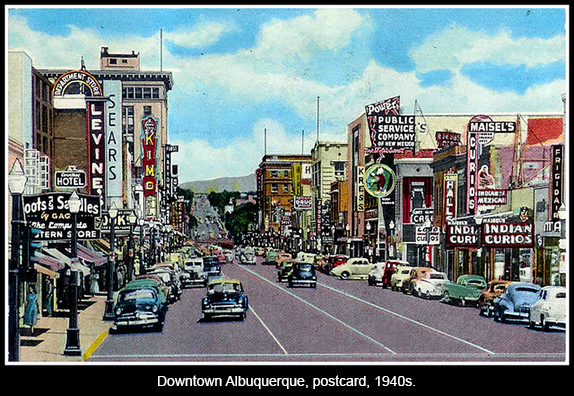

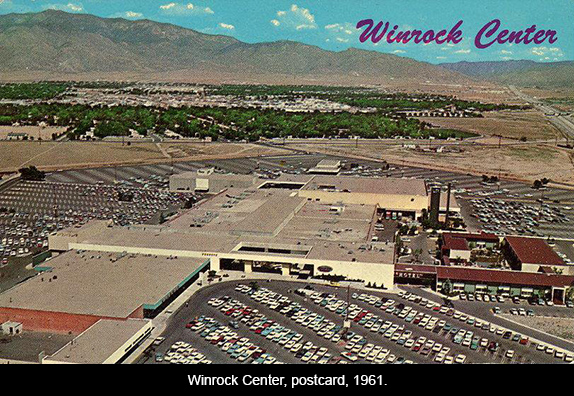

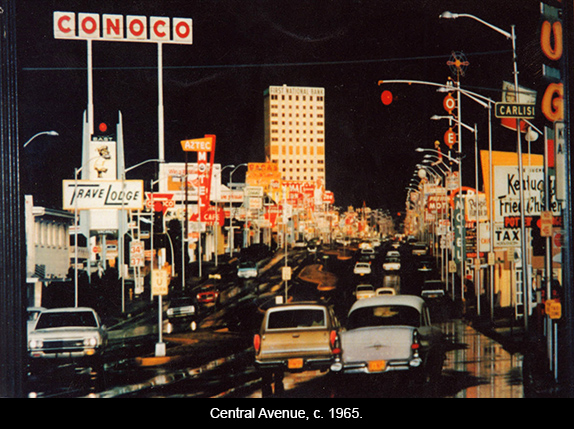

There can be no doubt that the mid-century marks a turning point for art in the city. The change can be linked to the city’s rapid growth after 1945, largely supported by the Cold War defense industry, which initiated an urbanization process that saw the city’s population double from some 95,000 in 1950 to just over 200,000 by 1960. Emphasis on the automobile, which had been a significant aspect of the city’s identity from the 1930s era of Route 66, and which had produced the string of motels and the dazzling display of neon all along Central Avenue, gained additional momentum during the 1950s with the installation of a new freeway system. The new car culture replaced the older centralized railroad hub-related downtown (just as the railroad-linked commercial district had displaced the original horse and ox cart trading plaza of Old Town) and initiated what was actually a sub-urbanization process. Shopping malls sprang up, streets inside the city were finally paved, and the city began its much lamented outward sprawl.

By the mid-1960s, despite the civic aspiration of progress, the harsh reality of the city’s built environment was defined by an unprecedented amount of asphalt and concrete. In a place given to sporadic boom-town impulses, all of that shiny-new steel and glass, aluminum and plastic, stood baking and glinting under the desert sun with all of its utilitarian complacency exposed. It sat side-by-side with the dusty lots and tumbleweed-clogged chain-link fences, the stucco and concrete block and eroded adobe of earlier generations. As Gus Blaisdell, who arrived in the city in 1964, once put it: “Albuquerque is, like America, a promise unfulfilled, hence always partly unkept, and so, always partly unkempt.”

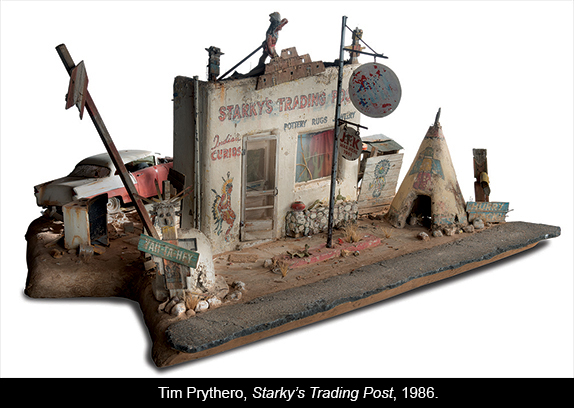

No one has captured that sense of failed promise better than Tim Prythero, whose Starky’s Trading Post, 1986, featured in “Visualizing Albuquerque,” gives a poignantly detailed glimpse of decay and loss at a shuttered roadside attraction from the bygone era of tourism.

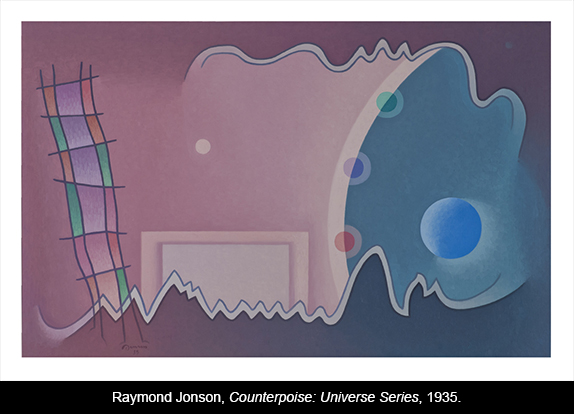

But 1950 was the year that Raymond Jonson opened his John Gaw Meem designed residence/studio/gallery on the University of New Mexico campus. From that time on, the University became a significant player in the Albuquerque art community and the impact of its art department must not be underestimated. The UNM art department attracted into its orbit artists from all over the country—as students, as faculty, and as visiting lecturers and instructors. Richard Diebenkorn arrived at UNM to do graduate study in 1950; already an advanced artist, he wanted only to utilize the GI Bill to further his development. Jonson’s influence and his support of Modernism’s embrace of abstraction was a strong influence on the unfolding direction at the university, and the influx of university-related artists from all over brought an international cosmopolitanism to the city at odds with the more narrowly focused regionalism enjoyed by local artists and their patrons. During the 1960s, with the arrival of Clinton Adams and Van Deren Coke at UNM, this trend intensified.

Albuquerque’s urban edge and the presence of the University is what sets the pursuit of art in Albuquerque apart from the Taos and Santa Fe colonies as they were in the early part of the twentieth century, and from what Santa Fe has become in more recent years. For artists drawn to Taos and Santa Fe, it was always the underlying sense of an old-world village, locked in time in a remote and dramatic landscape and harboring a blend of deep-rooted local ethnicities, that was the basis of the attraction. But for artists who elected to settle in Albuquerque, there seems to be a sense of resignation to the fact of universal urbanization as the ineluctable fate of the modern world. It’s a kind of realism (of acceptance) as opposed to the romanticism (of nostalgia) associated with Taos and Santa Fe.

V. B. Price has called Albuquerque “the city at the end of the world.” In part, his phrase refers to the city’s geographical isolation, in the same sense that the early Spanish governor Don Diego de Vargas described the territory of New Mexico as “remote beyond compare.” This, in itself, can be attractive for artists who would like to get as far away as possible from the oppressive overpopulation and overheated commerce and industry of America’s major urban centers. But perhaps there is a more apocalyptic note implied, and the dystopian city in the desert (with its historical links to nuclear armaments) is taken to be like the Australia of the “Mad Max” movies—a place where the few survivors of a universal holocaust resignedly try to eke out a life amidst the scattered remnants and ruins of a failed and defunct civilization. Of course, that apocalyptic attitude, too, is a form of romanticism, but in the era of late capitalism its sentiment can be felt throughout the world. (According to the United Nations, the year 2008 marked a tipping point in human history in which, for the first time, more than 50% of the world’s population is now living in cities, and this trend toward urbanization is vastly accelerating in developing countries.)

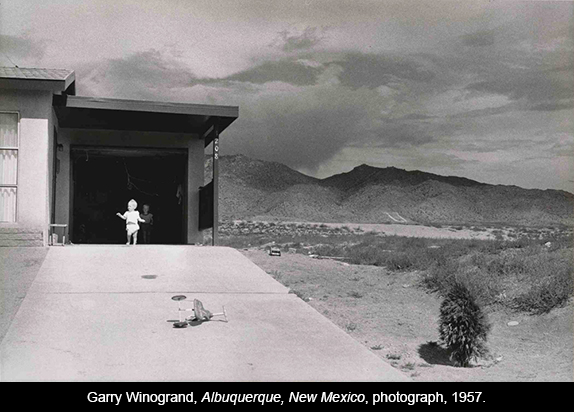

Perhaps the most striking image of “the city at the end of the world” in “Visualizing Albuquerque” is Garry Winogrand’s photo from 1957, picturing a crisis of innocence at the edge of suburbia, where the last house in a cheaply speculative development is poised uneasily on the frontier of an alien landscape. Alienation and displacement characterized the era, from the post-war period on, and the show’s catalog quotes Neal Young’s 1975 song, Albuquerque: “I’ve been flyin’ down the road / And I’ve been starvin’ to be alone / Independent from the scene that I’ve known – / O, Albuquerque.”

For those of us who arrived in the 1970s, Albuquerque was a more or less chosen place of exile. We were, many of us, internal expatriates, looking for a way to distance ourselves from the spiritual and cultural malaise of post-Vietnam America. The exasperated political disillusionment that marked the Nixon era was joined by what seemed at the time like an impotent rage turned self-destructively inward, which, in the art world, could be felt in the dismantling of art from within that began with post-minimalism. We needed time and space to recoup and reconsider.

In this internal expatriation, of course, we fell into a longstanding pattern of artists coming to New Mexico. From the beginning, they have been seekers, breaking away from the perceived dysfunction of contemporary society and searching for alternatives.

From the beginning, with the early founders of the Taos and Santa Fe art colonies, the lure of New Mexico for artists has been in its unique landscape and the local color of its Native and Hispanic cultures. While the latter provided alternative perspectives on how life might be lived, especially in respectful relation to the land, it was the land and its spatial remoteness that offered an experience of solitude that many artists covet. Here was a chance to escape the hectic pressures and the ills of industrialization and social unrest encountered in more densely populated regions. It was an escape not only in space but also time, which the local cultures traced back to a remote past of early settlement on the land. For the Hispanics that settlement dates back to the initial explorations of the sixteenth century and the reconquest at the end of the seventeenth, and for native peoples it stretches into even more remote regions of time. In New Mexico evidence endures of an antiquity of human presence on the land that makes it unlike any other area of the country, while the land itself wears time ruggedly on its face, marked in terms of geophysical eons that might as well be eternity.

The availability of this experience of one’s singular isolation in space and time is the source of the much-vaunted “spirituality” of New Mexico’s landscape environment. It has a particular appeal for artists, who tend to spend great amounts of time in solitude and in communion with their senses. It is available even to the residents of Albuquerque, despite the gritty clutter of the immediate surroundings. Partly this is because of the ease of access to an experience of the open land. But even in the heart of the city one is always conscious of the vault of the sky, the matchless quality of light in the high desert, and the vastness of space encompassed in the land. The city is situated in such a way that one is commonly aware of the stretch of horizon—with Mount Taylor looming on the edge some seventy miles beyond the stubby rim of volcanoes, and down below, the tired and parched mesa resting on the ribbon of the Bosque that clusters along the nurturing Rio Grande. On the east is the constant backdrop of the sheer bank of the Sandia Mountains, ineluctable, crusty and enduring as the turtleback that ancient people saw there, seasonally set aflame at sunset, and with the blue Manzanos trailing southward as far as the eye can see.

For many artists, the sense of Albuquerque as “the city at the end of the world” has been a source of solace. It is a place where one can work, far from the rat race of the competitive art market and of producing for the culture mill. And it is far, too, from the many pressures of an overheated art scene like New York, with its theoretical battles played out with incessant immediacy in the galleries and museums. Here, one has time to weigh one’s impulses and to give consideration to the work, the freedom to pay attention to what it wants to become.

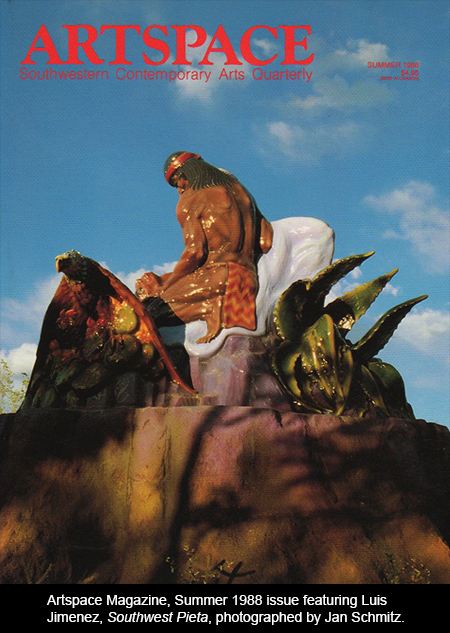

Yet, it’s not just the grittiness of Albuquerque’s urban environment, its awesome desert setting, and its societal mix that can be attractive and even stimulating to artists. You’d have to take into account the opportunities for affordable studio and living space, and the convenient accessibility of all of the urban amenities, supplies, and resources which make it possible to just get on with what’s important—the making of art. When we founded Artspace Magazine here in Albuquerque in 1976, it was largely because of the availability of affordable industrial printing and shipping in the city, cheap rent, and the presence of the intellectual community that had developed around the University—the vital bookstores and newsstands; the mix of artists, poets, and writers; and the places to meet and discuss the cogent issues of the time. (Yes, the Frontier Restaurant, our American-roadside default for Parisian café society.) The University ghetto was our version of Greenwich Village, a counter-cultural island in the city, featuring affordable living and intellectual stimulation. It was a practical decision to base the magazine here. But we also liked the city’s distance from the preciousness of Santa Fe.

By the late 1970s there was also a growing art community in Albuquerque’s downtown district. Artists had largely taken over a block along Central between Second and Third, installing studios and living quarters upstairs and opening exhibition spaces on the street level—the Meridian co-op gallery and Albuquerque United Artists’ alternative space gallery. (That entire block of buildings was eventually torn down, condemned because it was sinking. AUA’s gallery often had a pond of water in one corner since its floor was already slightly below the level of the sidewalk outside.) The activity extended on down south on Second Street, where a number of artists had studios and where, most importantly, Lise and Harvey Hoshour opened the Hoshour Gallery in 1977. Situated between the Sanitary Tortilla Factory’s M & J Restaurant and Harvey Hoshour’s architectural offices on Coal, the Hoshour Gallery set new aesthetic standards and provided the community with exposure to high modernist art and challenging installation works by such significant international artists as Daniel Buren, Clement Meadmore, John Knight, and Robert Therrien, as well as such innovative locals as Oli Sihvonen, Frederick Hammersley, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Terry Conway, Bill Gilbert, and Tim Prythero.

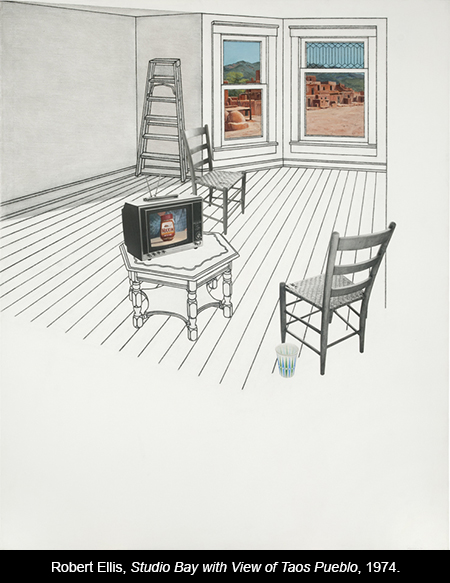

For a while Artspace had an office in the Sunshine Building. The KiMo Theater was renovated as a downtown performance space with a small gallery and a resident theater company called the Performing Arts Collective. The KiMo restoration was done by Harvey Hoshour, who also spearheaded a survey of available space throughout downtown, unused space in all of those empty buildings that could be made available and converted into studio workspaces and exhibition areas. It was all part of the city’s attempt to revitalize the defunct downtown. One of the pioneering efforts in that regard was the First National Bank’s First Plaza, which had already brought a new dimension of urban design to the downtown area. In its early days, the First Plaza’s underground Galería housed the Tamarind Restaurant (proudly displaying its collection of lithographs from UNM’s Tamarind Institute) as well as Bob Tomlinson’s contemporary art gallery, which showed Santa Feans Sam Scott, Eugene Newmann, Frank Ettenberg, Rebecca Davis, Harold Joe Waldrum, and Fritz Scholder, as well as Albuquerque painters Reg Loving and Richard Thompson. In 1977 Sterling Coke (son of UNM’s Van Deren Coke) opened the White Oak Gallery and Bookstore in the Galería, where he would give shows to local photographers and painters such as Raymond Jonson, Robert Ellis, Jane Abrams, and Carl Johansen.

Later on, and further down Central towards Sixth Street, local entrepreneurial patron Ray Graham sponsored another alternative-space exhibition venue called Café Gallery to showcase local artists, directed by Bonnie Verardo. (That space is now occupied by 516 ARTS, which has expanded upon Graham’s groundwork to produce a bustling Kunsthalle-style approach of changing theme-oriented exhibitions and public programming. In the 1990s, Richard Levy established a stellar gallery next door.) For a while, another group of entrepreneurs had renovated the two-storey building on the southwest corner of Sixth and Central, dividing it into artists’ lofts. On the opposite corners, as the momentum of the 1980s economic boom got underway, a couple of other galleries appeared. Kris Krohn and Karen Reck set up the Krohn/Reck Gallery, and at about the same time, on the other side of Central, facing onto Sixth, Ray Graham opened the Graham Gallery, directed by Kathleen Shields and Anne Cooper. Soon he added the Raw Space gallery next door and the Café Gallery across the street.

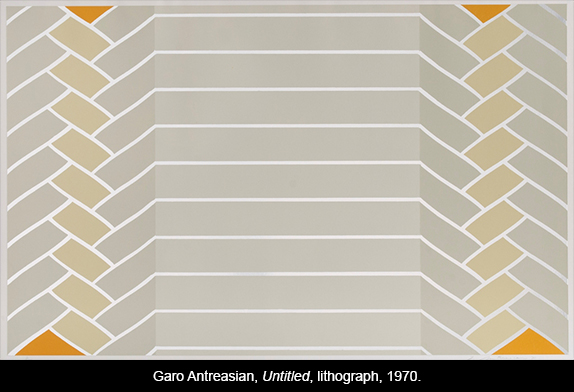

Out on Rio Grande Boulevard, just past Old Town, Patsy Catlett spearheaded the Wildine Gallery, which opened in 1979, showing Nick Abdalla, Clinton Adams, Garo Antreasian, Wanda Becker, Robert Ellis, Raymond Jonson, Aaron Karp, Leonard Lehrer, Frank McCulloch, Harry Nadler, John Rise, Enrique Montenegro, and many others. The Mariposa Gallery was also active in Old Town, managed by Peg Cronin and Faye Abrams. Although they showed Ken Saville’s drawings and Peter Bilan’s sculptures, Mariposa’s emphasis was on fine crafts, and a reminder that the era saw a brilliant outpouring of creativity across all media, expanding beyond traditional functional attitudes and extending from the ceramics of Bev Magennis, Rick Dillingham, and Barbara Grothus, to the textiles of Nancy Kozikowski and Joan Weissman.

Exhibited at the Wildine Gallery

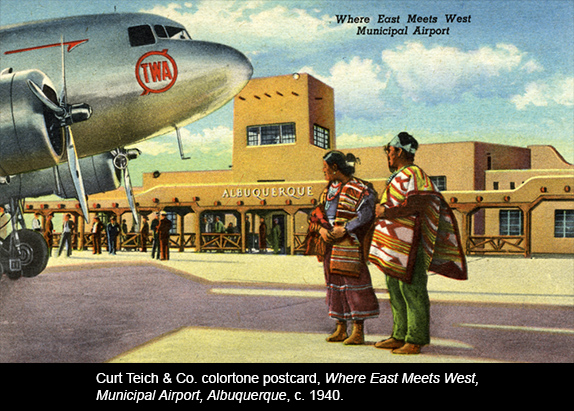

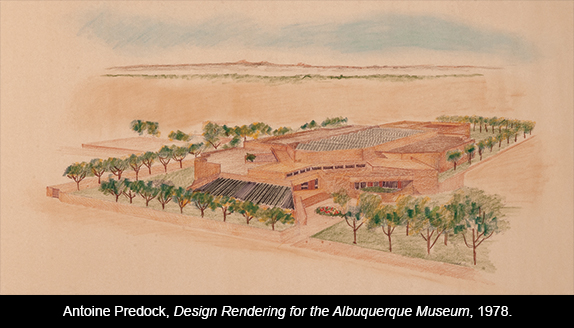

It was in 1979 that the Albuquerque Museum of History and Art opened its new building in Old Town, designed by Antoine Predock. The Museum had been initially operating in the old 1930s airport building, mounting exhibitions on temporary wall-dividers within the enchanting and historically resonant space of the building’s lobby. With its flagstone floors and magnificent log vigas, the old airport had provided visitors arriving in the city with a thrillingly exotic experience of the region’s uniquely romanticized Pueblo Revival style. But, despite the special frisson I remember feeling while viewing Cubist paintings by Braque and Picasso in that setting (in an unprecedented traveling show of early European modernists), the airport space was not very conducive to showing art. So it was especially important when the Museum got its own building with adequate exhibition spaces and could take on a leadership position in acknowledging the community’s artists. Predock’s brilliant design, bermed into the earth, partly underground and drawing on solar energy, had a purposely low profile in keeping with native architecture and the Puebloan peoples’ respectful humility in regard to the earth. With its new permanent home, the Museum was now able to establish its identity as a cornerstone of the community’s art and culture, symbolically rooted in its native soil.

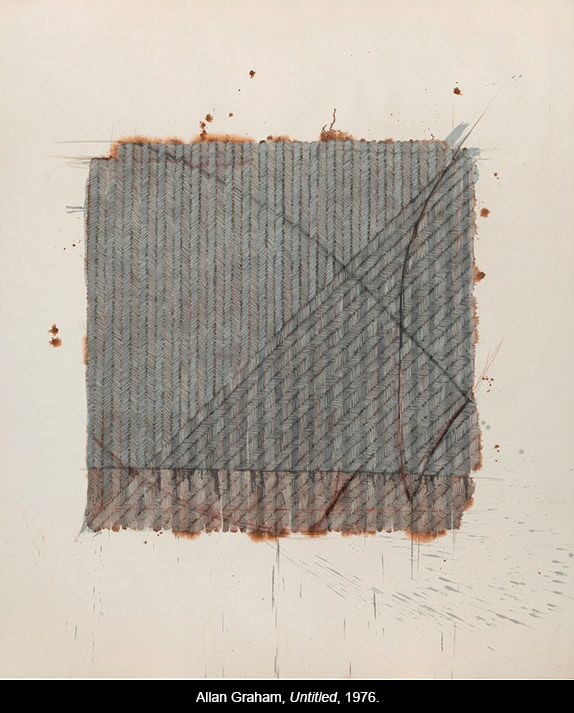

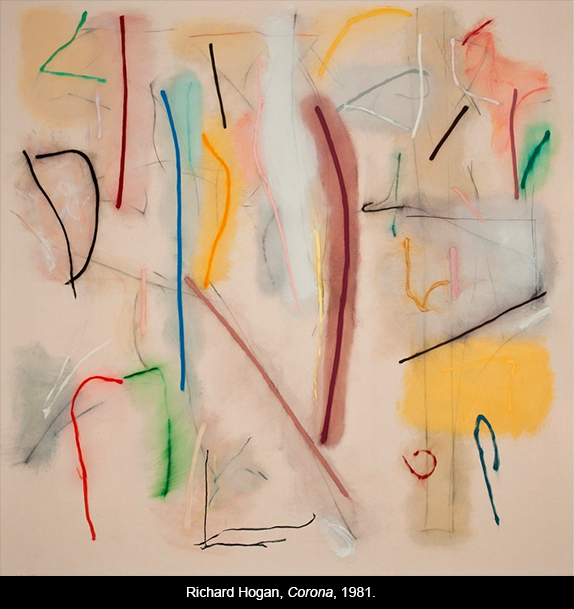

All of this discussion of the downtown and Old Town areas, however, leaves out one of the most significant of the pioneering showcases for new art in the city at the time—the Motel Gallery out on North Fourth, whose beginnings in the mid-1970s actually predate most of these other efforts. Operated by artists Allan and Gloria Graham, the gallery was housed in one of the units of an old motor court that once serviced Route 66 when it doglegged up to the north. The Grahams had converted the other adobe units into a variety of studios and workspaces, some of which they lent out to other artists. It was there that I first saw the work of Richard Hogan, Terry Conway, Bill Masterson, Bruce Lowney, and the Grahams. A vital spirit of camaraderie and competition existed among the artists associated with the Motel Gallery, and all of them had received at least part of their training at UNM. But you could sense a shared sensibility based on issues of line and space, the immediacy of drawing impulses, and of earthy pigments broadly or thinly applied, often to seemingly raw and unprimed surfaces. And you could also sense in these works an awareness of the spontaneity of Zen aesthetics, and an appreciation for the vast vacant dusty spaces of the surrounding desert landscape and for the ancient pictographic and ceramic remains of its earlier inhabitants. Except for Lowney, none of the artists actually depicted any of these specifics derived from the land, but the desert lent its character abstractly and atmospherically in the austere formalism of their approach. The power of the place is there in the work, and in 1982 the Albuquerque Museum acknowledged the contribution of these artists (and a few others) in one of its most coherent and well-curated presentations of local art: “In Place,” with a catalog tribute penned by one-time Placitas poet Robert Creeley.

The Motel Gallery Artists

All of these venues for contemporary art made Albuquerque an exciting place to be in the late 1970s and 1980s. But it must be admitted that there have always been (and continue to be) two insurmountable obstacles for commercial galleries in Albuquerque: (1) There is simply an insufficient number of sophisticated art buyers in the city, and (2) the local dealers have never been able to compete with Santa Fe as an art market. With the exotic allure of its multi-ethnic and historic adobe charisma, and with its walkable village-like density of galleries, Santa Fe has been able to attract a more international clientele of visitors and part-time residents, many of them with sophisticated taste and a genuine commitment to culture that is a prerogative of wealth, as is evident in the support shown for the Opera and the Chamber Music Festival. Even Albuquerque’s few hometown art aficionados would tend to find it more attractive to take a pleasant drive through New Mexico’s incomparable landscape and spend the day in Santa Fe, going around to all of the galleries and having lunch in one of “The City Different’s” fine restaurants, than they would braving the bleak concrete and asphalt of “The City Indifferent” to seek out an art experience and make a purchase.

Just as there is no art market in Boston or Baltimore or Buffalo or even Philadelphia because of their proximity to the dominant cultural leadership and established marketplace of New York City, there is no viable art market in Albuquerque because of the closeness and more successful promotional positioning of Santa Fe. During the early 1970s the best exposure for Albuquerque’s artists was at the biennial exhibitions at Santa Fe’s Museum of Fine Arts (discontinued after 1978). And from the mid-1970s through the 1980s Albuquerque’s best artists were among the mainstays of Santa Fe’s best contemporary galleries—Hill’s Gallery, Janus, and especially Linda Durham.

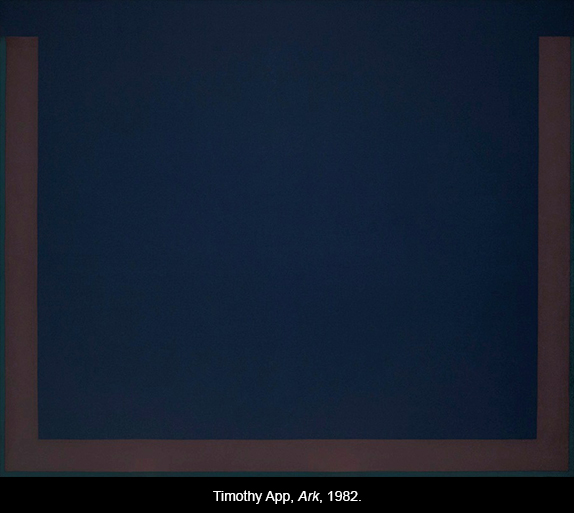

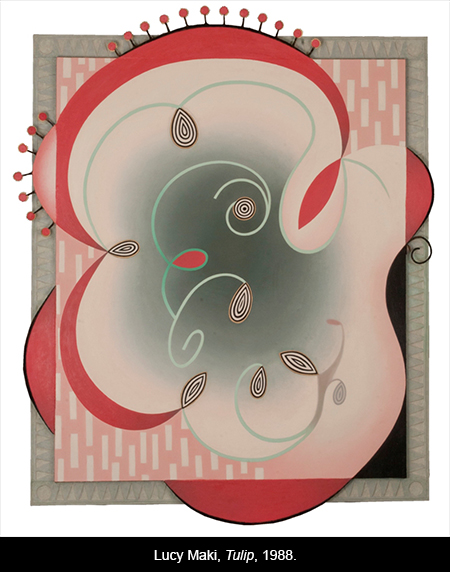

Linda Durham deserves special mention because she provided the most consistent exposure for a core group of Albuquerque’s best painters, together with other artists from the region of equal quality, in Santa Fe’s growing market. Beginning in 1979, she maintained a program of singular dignity. The consistent high-level of seriousness and quality among Durham’s artists and her respectful presentation was in distinct contrast to the unevenness and sometimes helter-skelter approach of most of Santa Fe’s galleries when it came to selecting artists for their stables. Over the years Durham handled the work of Albuquerque artists Allan and Gloria Graham, Richard Hogan, Susan Linnell, Lucy Maki, Constance de Jong, Timothy App, Margaret Newman, and William Masterson.

Exhibited with Linda Durham in Santa Fe

But I think it’s important to note that when we started Artspace Magazine in the mid-1970s, Santa Fe was not yet a viable marketplace for adventurous art. Santa Fe had gone to sleep during World War II and did not begin to wake up again until the late 1960s with the activity of Fritz Scholder at the Institute of American Indian Art (and that of his gifted and short-lived pupil T. C. Cannon) and the arrival of such artists as Sam Scott, Eugene Newmann, Doris Cross, Jean Promutico, Warren Davis, Frank Ettenberg, Harold Joe Waldrum, and John Connell, who brought a fresh sensibility and a wave of new ideas to the local scene. There were few galleries, and at first only Margaret Jamison opened her wall space to adventurous art. Soon, however, the needs of the new artists began to be met by the opening of Hill’s Gallery in 1975 by Megan Hill, a recent graduate of UNM’s art department who had independent means and could afford to take a chance on the nontraditional approaches of her fellow new generation of artists. Bob Tomlinson, on the other hand, was so concerned about the receptivity for new art in Santa Fe that he moved his upstart enterprise to Albuquerque in hopes of tapping into the potential of a more open, urban and cosmopolitan environment. In any case, Hill’s was soon followed by the opening of Janus Gallery, and Bill Benton’s Gallery of New Mexico (funded by Joan Clarke and soon called Clarke-Benton Gallery). But Santa Fe’s real turnaround came with the arrival of Elaine Horwitch in 1977 with her massive advertising budget. Joining such traditionalist big spenders as Forrest Fenn and Gerald Peters—who, along with Nat Owings, were mainly promoting the “blue chip” artists among the founding Taos and Santa Fe colonists to rich Texas buyers—Horwitch basically did the most to put Santa Fe on the map as a market for more than just traditional regionalist and tourist art. The main drawback with Horwitch, however, was her taste for the flashy and slick, which would become endemic to Santa Fe.

This is not the place to discuss the successes and failures of Santa Fe’s art scene, except to note that New Mexico’s dependence on transient art buyers has always been a serious flaw in its sustainability. From the beginning, from the Taos Society of Artists to Santa Fe’s Cinco Pintores and to Jonson and Bisttram’s Transcendental Painting Group, the banding together of artists into groups was not just about sharing ideas. Instead, these groups were specifically formed in order to market their art work out-of-state—in Chicago and New York and San Francisco. And it’s important to remember, too, the deals struck early on with the Santa Fe Railroad, in which the artists cooperated with the railroad industry to market the area (and its art) to tourists. In more recent years, of course, the successful promotion of “Santa Fe style” as an allied component of Santa Fe’s art scene—with all the attendant romantic exoticism and local color—contained many drawbacks. Not the least of these was its inevitable attraction for wannabee parasites. By 1986 Santa Fe was fully “Carmel-ized”—overrun, like Carmel in California, by a sticky-sweet inundation of tourist-oriented calendar art (How much orange, pink, and turquoise paint does it take to make eye candy?), and by howling coyotes, bronze Indians and bears and long-legged horses, whirligigs and watercolors, beaded and feathered macramé, and starry-eyed “New-Age”-affiliated art manqué.

This kind of commodity product and merchandising is commonly known as “kitsch”—art’s evil twin—made to sell in a market economy to the sort of people who have already been sold a certain comfortable and consumable idea of art, and made by people who have already bought into a certain conformable and convenient idea of what it is to be an artist.

Except for a brief moment during the booming economy of the 1980s, it has always been virtually impossible for an artist to make a living showing only in New Mexico. The limited size of the local art market (and of the local economy in general) has meant that the pricing of the artwork tends to be low. Among the things that struck me in the early days of my experience on the New Mexico art scene was not only the surprising amount of art being produced here, but the extraordinarily high quality of much of it. Yet the low dollar value of the prices did not correlate with the high aesthetic value of the art. It bothered me that New Mexico’s best artists were painting on a level that equaled that of their counterparts in New York and Europe, but that they had not received recognition. One reason for producing a magazine was to provide exposure and present the case for the significant accomplishment of New Mexico’s artists, and to use that medium to communicate their achievement both within the region and to the art world beyond.

Another thing that struck me about Albuquerque (and Santa Fe and Taos) was the extent to which art was actually and almost casually accepted as an aspect of the enhancement of daily life. By this I mean the number of homes and offices I went into where local art was displayed as a matter of course. I have not seen this in other parts of the country. It goes without saying that a lot of this is a reflection of a sense of belonging, a kind of regional chauvinism that recognizes that New Mexico is a special place with a unique heritage and landscape, and a desire to identify oneself (or one’s business) with it through possession and display of its imagery. This is a part of how one makes one’s home here, a part of the sense of being at home. And there’s no question that a lot of this operates on a kind of lowbrow, knee-jerk level of decorating with Native American kitsch and R.C. Gorman prints and easily satisfying landscapes from the Watercolor Society. There is a deeply conservative strain in Albuquerque’s make up as well, holding onto an imagined past and devoted to a form of “traditional” art. But I was quite amazed at the number of homes where you would see a painting by Andrew Dasburg or Raymond Jonson hanging on the wall. And it became quite common to see prints from Tamarind.

It seems that Albuquerque has always harbored a modest interest in serious art, a small—but in terms of per capita, quite astonishingly large—number of informed, college-educated citizens with a genuine concern for cultural affairs who will occasionally want to acquire for themselves a piece of genuinely challenging art. It was this potential clientele that Albuquerque’s burgeoning galleries in the late 1970s hoped to cultivate. And, to be honest, it was to this sort of interested party that Artspace Magazine was largely addressed; and indeed, much of its support came from this sector, who rallied to become patron subscribers or board members of the struggling non-profit publication.

Editor's note: This piece has been updated for accuracy regarding the history of Ray Graham’s studio.

February 24, 2015