In the 1940s the legendary ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes came to the Sibundoy Valley in the Putumayo region of southern Colombia to research the cultivation of rubber trees for the US war effort and in his spare time pursue his abiding passion, the study of psychoactive plants and their use by native cultures in the upper Amazon region. I became aware of Schultes years ago through Wade Davis’ book, The Lost Amazon, which contains Schultes’ extraordinary photographs taken during his travels. His solemn and formal compositions documented a reality that in a scant 60 years or so has all but disappeared. In the photographs in which he appears, Schultes’ gaze is somber and faintly accusatory, witness to something sublime that will never be seen again.

I had the opportunity to visit a much different but still beautiful Sibundoy Valley a while ago with a Colombian friend, Duván Rivera Arcila, whom I met by chance one afternoon in Quito at the Confederate Bookstore, a thoroughly reasonable place despite the name’s reactionary associations. Because of its venerable status as the oldest English-language bookstore in Quito, none of its owners has entertained the notion of changing the name. Its current, and third, owner, Justin Trullinger, is a friendly guy with a slight resemblance to a certain high school chemistry teacher of recent television notoriety, or in his more intense moments, a late van Gogh self-portrait. Justin is from Iowa and has ended up in Quito via circuitous fashion, as many here have. His wife, Helen, is from Southend, on the Thames estuary. They have a delightful and voluble three-year-old, blond-haired, blue-eyed daughter whose name is Megan.

I was talking with Justin this particular afternoon when Duván happened into the store, asking if there were any books by Richard Evans Schultes. There weren’t, but my connection to Schultes was about to take an unimagined step closer. Duván and I immediately began to talk about the great ethnobotanist who, we discovered, was a mutual hero. Duván’s English is about as good as my Spanish, which is to say two or three notches above survival level, but we communicated well enough, and with our shared enthusiasm for Schultes we quickly became friends.

Duván is a high school teacher with a degree in philosophy, a profile similar to my own, though it was quickly apparent that he was more serious and knowledgeable about spiritual matters than I, particularly concerning the use of psychoactive substances. He was vacationing in Ecuador with a couple of friends and returning soon to Colombia. In two months, coinciding with my own break from teaching in Quito, he was going to the Sibundoy Valley to participate in an ayahuasca (in Colombia, yagé, yah-HAY) ceremony with a noted taita (elder, or shaman). Ayahuasca, which Schultes called “the vine of the soul,” has always interested me, but only in the context of a traditional ceremony under the guidance of a true teacher.

Ayahuasca, or yagé, is a psychoactive brew made from the Banisteriopsis caapi vine found in all parts of the Amazon and has been used for many hundreds of years as a highly potent purgative and healing medicine. It is also a doorway to normally inaccessible psychic worlds, facilitating the understanding of connections between inner and external realities. Such knowledge, or understanding, one intuits, was more readily available or more naturally woven into the fabric of cultures in the past. At the very least there was less distraction from opportunities to contemplate the essential. No more. Our technocratic and hyper-capitalist culture has turned us into mere units in a consumerist assembly line, addicted to material pleasures and digital opiates, the substance of such a life an endless series of temporary distractions that keep us from the possibility of contemplating any sort of deeper reality. Having spent a good deal of my life in rebellion against the glittering materialistic and ego-driven allurements of my native culture, scratching somewhat futilely at its steel and glass surface in search of inner sustenance and meaning, it is natural that I might be interested in something like ayahuasca, as are many others these days. As with Tibetan Buddhism and the Dalai Lama twenty years ago, there is more than an element of faddishness to the ayahuasca movement, yet another example of Westerners “discovering” (and consuming) these ancient spiritual practices, losing interest, and moving on to the next. One can be cynical about this and at the same time admit it’s not necessarily a bad thing, elements of these “discoveries” as part of a cross-pollination process that inevitably alter the cultural DNA. The recent phenomenon of “ayahuasca tourism,” naturally enough, has attracted charlatans posing as shamans. In April of 2014 in Mocoa, Colombia, a young British man died after a ceremony. Those close to the story say the ritual was bogus and something other than ayahuasca was consumed. But in spite of the uncertainties surrounding the sudden rise in popularity of ayahuasca, and my own lack of experience in these matters, there was quality about Duván that I trusted. When he asked if I wanted to go with him to Sibundoy, I said yes.

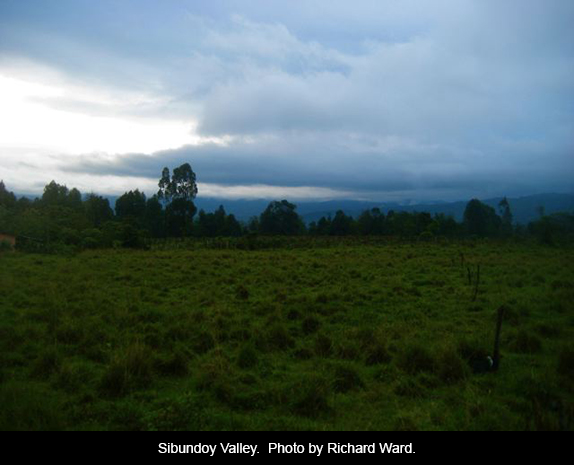

Now, two months later, with only an intuition of what I might be getting myself into, I travel by bus from Quito to the city of Tulcán, in the north of Ecuador, to Ipiales in Colombia, and from there to Pasto, where I spend the night in a hotel near the bus terminal. In the morning I meet Duván at the terminal and after breakfast we travel by van to the Sibundoy Valley and to the home of the taita. In the town of Sibundoy we have almuerzo in an open-air restaurant full of handsome and healthy-looking people, mostly Inganos and Kamentsa, the two main indigenous groups of the valley. The taita is Kamentsa. After lunch we buy some food for our stay and take a cab that deposits us at the head of a wet dirt road that leads to the taita’s farm. It has been raining in Sibundoy. We pass orderly fields in a green and fertile valley, full of corn and fruit. The houses are in good repair. There are many dogs but they don’t bark. Some approach with their tails wagging. All is quiet.

The taita and his wife greet us at their home, a modest concrete block affair, painted white, surrounded by cornfields and pasture. He is reserved and unassuming, compactly built, with dark skin. His wife is lighter complexioned and equally reserved. They appear to be in their fifties. The taita seems an ordinary person, someone you’d pass on the street without notice. Without smiling he shakes my hand lightly and I respond deferentially, conscious of my stereotypical role as the sincere gringo supplicant. This guy has seen dozens of people like me. We put our stuff in the ceremonial room, where we will also sleep. At one end is an altar of sorts, with different items of significance to the ceremony laid out on a table and more on shelves next to the table. On a wall above the table is a painting of a tiger, its yellow eyes gleaming menacingly. Hanging next to the tiger are various other ceremonial items, small gourd rattles, bunches of colorful feathers tied together, a feathered crown, flutes, a picture of Jesus. Owing to the Catholic missionary conquest of the area in the past, elements of Christianity have filtered into the indigenous culture and thus into the yagé ceremony. Several ojos de dios of different sizes hang from the ceiling.

After stashing our backpacks and sleeping bags on reed mats in the room, Duván and I go for a walk. I am a little anxious and am hoping that we will have a couple of days to acclimate to the surroundings before the ceremony, but Duván informs me that there will be one tonight. I am not sure I am ready for this, but I resign myself to the reality. The ceremony generally begins around 11 and lasts until dawn. It is now about four o’clock.

We walk down a dirt road surrounded by fields of corn and fruit, talking about yagé, Sibundoy, the taita, Schultes, Wade Davis and William Burroughs, who’d had a tumultuous experience with yagé in Peru, violently sick, dragging himself through the dirt, feeling death and ultimate resurrection with bejeweled jaguar-anaconda visions. Ayahuasca is not always so kindly. Sometimes people have horribly frightening experiences from which they have difficulty recovering. One is advised to be of a relatively calm state of mind, to have one’s system cleared of prescription drugs and stimulants. I have high blood pressure and am taking medication for it. I’ll probably be all right, but a small worm of fear crawls through the back of my mind. I’d drunk ayahuasca once a couple of years before in the Ecuadorian Amazon in a kind of half-baked ceremony and nothing much happened but for a few vivid Technicolor cartoon dreams after I went to bed. I hadn’t even gotten sick. Diarrhea and vomiting are accompanying elements of the ceremony, especially the vomiting. These are the physically purgative functions, clearing the body of baggage and toxins, opening the vessel for the spiritual and psychological journey that follows.

It is close to six o’clock and getting dark. Returning to the farm we meet a couple and another man. It is overcast and a slight mist surrounds us but I can see their eyes and feel their energy, especially that of the men. Nico and Maria are an Italian couple in their twenties. The other guy is Gabo, a tall Hungarian with long, lank dark hair, wearing loose indigenous clothing. Nico and Duván speak animatedly and rapidly in Spanish, leaving me far behind. For the first time this evening, but not, as I will discover, the last, I feel a bit lost and helpless, but everyone is friendly and I am part of the group. I have begun the process of preparing myself, not only for what happens in the ceremony but in a larger sense, to accept what comes, and to let go. At 67, I struggle with the conflict between looking back, trying to hold on to what inevitably slips away, and looking ahead, into the abyss. Facing death is a direct acknowledgement of the present, the slow unraveling of the physical self, something that astonishes on a daily basis. Can this be happening to me? That it happens to everyone is of little solace. This is something I know I will face during the ceremony, whatever other mysteries and surprises it may hold. I must begin the process of saying goodbye to someone I know so well and who at the same time remains so much of a mystery.

We eat a simple dinner the taita’s wife has prepared and move to the ceremonial room, the same room where we will sleep. It’s about four hours until the ceremony. Since first introductions I have not seen the taita, but one of his sons is here, and also his nephew, an exuberant and uninhibited boy of about eight. The taita’s son, who will assist in the ritual, jokes with Nico and Gabo. Nico is a photojournalist and is doing a story on the taita. The taita is considered one of the leading practitioners of the yagé ceremony in the Sibundoy Valley. He has devoted his life to keeping the tradition alive and has trained two of his sons to succeed him. The hope is that his nephew will also become a taita some day.

Everyone lies down to rest or sleep before the ceremony. The lights are dimmed. A few more people have arrived from the community, a young man and a woman, separately, both in their thirties, and two more women, a couple, who sit so closely together they are like conjoined twins. They seem obvious lovers, one in her mid-thirties, the other in her early twenties. They cover themselves with a blanket and sleep. I watch them as I rest. Every move they make, every shift in position, is synchronized. There is some deep connection between them, as if they share one brain and nervous system, the same thoughts and dreams. When one moves, the other lifts the blanket to accommodate the change in position, at the same time moving her body in a corresponding fashion. Sometimes the movements happen quickly, like a school of fish rapidly changing directions, a kind of sensory integration that strikes me as extraordinary. All this happens as they sleep. A few times they awaken, together, then fall back asleep. I call them The Two Who Are As One, a stereotypical native appellation, though I haven’t been thinking of that.

The taita is scarcely to be seen. Duván sleeps. Gabo has retreated to his tent outside. Nico and Maria talk quietly. All the rest, the man, the woman, the lovers, The Two Who Are As One, sleep.

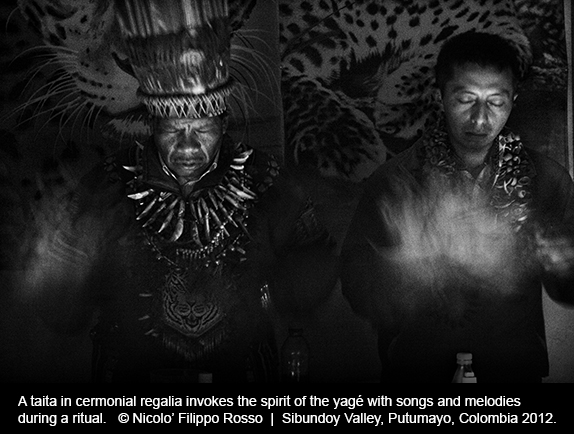

Around 11 p.m. music begins filtering through the speakers in the room, drums, chanting, flutes. The taita appears, busying himself around the altar, putting things in place. There is a bottle with brown liquid, next to it a cup. He disappears for a moment, comes back, lights candles, and puts on a headdress with colored feathers. The electric lights go off. His son comes into the room and sits. People stir, wake up, focus their attention on the altar and the taita. Gabo has appeared, almost mysteriously, from his tent and sits on a mat, his knees drawn up to his chest. Duván sits cross-legged. The Two Who Are As One watch attentively, the blanket wrapped around their shoulders. Everyone waits.

Without any particular gesture or formality, the taita, seated behind the altar table, begins to chant over the stuff in the bottle, the yagé. His son lights a brazier of copal and fans the smoke with a bundle of feathers. The chanting is in the rhythmic, haunting style of the yagé ritual. There are different varieties of yagé and tonight we will be drinking “tigre” (tiger), one of the more potent brews. It is said tigre will take you to difficult places, but you will be better for it afterwards. I hear references to the animal during the chanting. The room is dark but for the candles around the altar. Everyone is focused on the taita, who after a few minutes stops chanting and drinks the first cup of yagé.

Starting on the taita’s right and going around the room counterclockwise each person comes to the table and receives the cup of yagé that the taita has poured and blessed. Each holds the cup in silent reflection, some for a prolonged moment, some not so long, and after a ritual “salud,” or “buena pinta,” followed by a like response from the group, drinks the earthy, bitter brew, some swallowing quickly with no particular regard for the last drops clinging to the inside of the cup, getting the potent stuff down, some holding their heads back and taking every bit, as if to embrace the ensuing journey in its totality, darkness as well as light.

With my turn I pause a moment without thinking anything in particular, the eyes of the group fixed on me. Before drinking I try to open myself to the moment, drop all the bullshit right there and then, expose myself, come out from hiding. I am ready for what comes. I want it all. I say “salud,” lift the cup slightly in offering, to what I’m not exactly sure, lean my head back, and drink it down, all of it. The stuff is strong, causing a slight involuntary shudder. I return to my place and wait.

The taita chants, his son walks around the room with the brazier, fanning the copal, blessing each of us. Then, quiet. For the moment, the taita has stopped chanting. There is nothing but candlelight and shadows, each person in their own space, waiting. The yagé settles uneasily, a foreign substance beginning the process of absorption through the cells of my stomach, into my blood stream, to my brain, the spiritual emetic within, no turning back.

I know that the journey will commence with vomiting and this is what I wait for. My first experience in Ecuador had none of this, a letdown. I feel a mixture of anticipation and unease. Time passes. Forty-five minutes, an hour. I feel slightly nauseous but nothing else. My head is down, eyes closed. I am impatient. I am aware of others getting up, walking out of the room, vomiting outside. I am thinking that there is something about me that is resistant to yagé. I am disappointed, restless. This is bullshit. I feel a sense of relief too. Perhaps I won’t be going through la tormenta ayahuasca after all, no sickness, agonies, visions: no hell—or heaven, either. The music, drums, and chanting come from far away, but I know it must be the speakers in the room. I feel a curious double sensation of inner and outer realities, the inner, tangible, intensely questioning, alert, the outer, distant and muffled.

The taita’s son appears, looming over me, asking if I want another cup. It has been about an hour. Since I am feeling almost nothing of what I think I am supposed to be feeling, I say yes. There seems to be a lot of activity in the room but when I go to the table I see people sitting quietly, absorbed in their own worlds. I drink another cup and sit down. Ten minutes or so later I feel sick. I get up and go outside to the pasture next to the house and out it comes, violent and strong. I am doubled over, heaving. It is good. Finally.

After my stomach has cleared, I stand up somewhat shakily and look around. Gabo is ten yards away, playing a mouth harp. I have vomited but feel nothing else. The night is slightly overcast, a few clouds, and behind them, stars. At least I have been sick. A good purging. But other than that, nothing of the legendary visions, or feelings, or whatever the medicine might have in store for me.

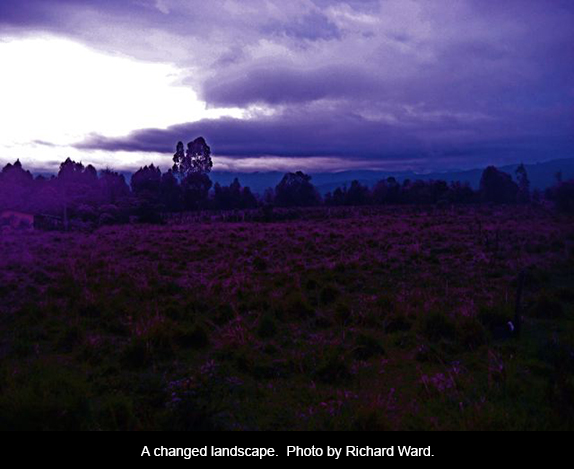

I decide to walk down the path to the dirt road alongside the farm. There is a stump of wood between the path and the road and I climb over it, taking a couple of steps down the dirt road, beginning to feel a little strange. I look up at the sky. The clouds are a delicate rose pink cotton and behind them the deep blue night sky is filled with crystal points of light. The pasture next to the taita’s house, ordinarily a rough terrain of dirt and large clumps of grass, is a geometric carpet of red, blue, and green crystals. The bushes next to me are brilliantly crystal, and geometric, like the pasture, illuminated, as if their leaves have absorbed every bit of available light, transformed to a mass of tiny lucent chandeliers, delicately faceted, alien, slightly menacing. I dare not touch them lest they shatter.

The awareness of ordinary time and place, of self and ego, is giving way to something different, a strange world of crystals and fractals, a silent, powerful presence, each blade of grass, each fence post, everything, alive with consciousness, strange and slightly threatening. I am far from the taita’s home, vulnerable, a little afraid. I must get back. The stump, or barrier, whatever it is, seems insurmountable, the act of raising my feet almost impossible, as if I am drunk. I make it over and pause to look around, anxious to get to the safety of the house and the group. But I cannot move. All around me is a glistening geometry of merging colors, alien but familiar, ayahuasca images from paintings I have seen. But I must move. I can barely walk. I am afraid to walk. I will fall down.

The desire for the safety of the house pushes me forward, step by tottering step. Ahead, light, community, shelter, out here another world closing in on me with its strangeness. I come to a small ditch perpendicular to the path with a board running across it. The ditch, no more than two feet wide, is now the Grand Canyon, the board a thin line. I force myself onward, the board swaying and sagging like a tightrope. I make it across and stop, absorbed now in the shining foliage next to the path, each leaf crystal, slightly forbidding, a geometry of repetitive patterns. I am completely fascinated, awestruck. There is no question that I am now in a different world. Out of the darkness a ghostly figure appears in front of me, instructing me to open my hands in a supplicatory gesture, whoever it is, perhaps the taita, anointing my palms with some kind of herbal-smelling liquid, pressing them closed. Instinctively I raise my hands to my face in a prayerful pose, a shift in the journey, away from the strange exterior world and inward, back to myself, or something approximating myself. It is perfect that the taita, or whoever it was, has come along at this moment. I am lost and it is time for a different direction.

With the shift to a more inward focus comes an increased desire to be with the others, all of whom are in or around the taita’s house, my walk down the path and onto the road an odyssey that has occurred in another dimension, an excursion into an alien environment visually strange and psychologically intimidating. I am not myself in any sense that I am familiar with. I am hollow, insubstantial. Near the front of the house I stop to look at the backs of my hands. They are stripped of skin, revealing bones reflecting crystal light.

Fascinated and horrified, I stare at my skeleton hands for several minutes until I can no longer bear it. Death is with me. Another of my preoccupations, the intense attachment to self, bones mocking and admonishing this steady partner I have know for so long, no more than a small charge of finite energy inevitably wearing down, transformed to something other, dust and powder, to what purpose, annihilation, but something else, certainly. I am charged with the presence of the others around me, all younger than I, their vital energy, the inevitability of their decline, the pre-determined journey, intense love and empathy for them, their striving, passion, and struggles, I, the other, the observer, the outsider, connected profoundly as sure as the bones beneath my aging skin, all of us wandering souls absorbed in our own concerns, but within a radius, close to the source, the taita, each other.

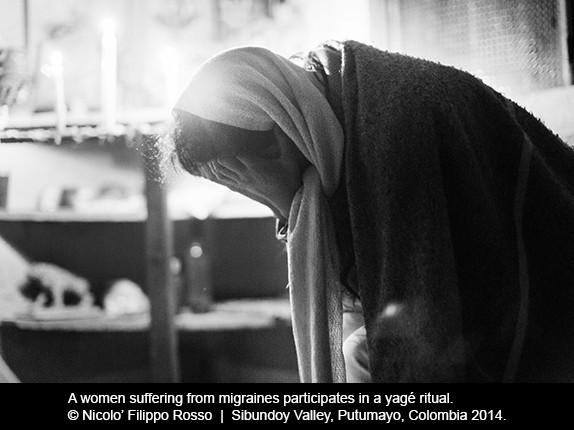

In front of the entrance to the ceremonial room people are doubled over, a chorus of deep convulsive purging. A few shaky steps into the shining pasture for a last marveling look, a passing ghost, whispering, the grass a fractal, colored jewelry. Back at the house people absorbed in different worlds, strange, halting postures, a quiet, introspective bedlam. A woman lying down on the concrete porch, her head against a post, in deep distress. Others are standing still, staring into the space of their own worlds. I sit next to the woman, my hand on her shoulder, knowing the nature of her problem. Another woman sits next to her, talking quietly. I stare at the ground which is dividing into colorful, shifting patterns until I am afraid and look away, get up, and move unsteadily to the perimeter, sick again, bent over, each cell in my body convulsing, letting go, cold, shivering, Nico or Duván putting a hand on my shoulder, inquiring. Yes, I am. Yes, I am. Okay. I, am, not, I.

Inside a candle-lit room filled with copal smoke and song-chanting, people moving around, returning to their places, sitting, a shift in mood and energy, the taita laughing softly, murmuring, a moment’s laxity verging on chaos, one phase leading into the next. No more fractal visions but now in another world, deeper into a mystery that is my vanishing self, death and loss of ego as a vine or tendril snaking around the room pulling me together with everyone else, what we have seemingly lost, that which keeps us joined in life and graces our death, what I am now and from which I do not flinch but regard directly, as it becomes not something terrible and alone but instead a natural, enveloping mother that covers everyone in a blanket of compassion. The taita intensifies the rhythm and begins playing a harmonica, a haunting, insistent refrain that is not so much music as a force of spirit, an instrument of intention, taking us deeper, pulling us together, beyond sadness, though the sound is infinitely sad, into a realm of pure compassion and healing. This extraordinary substance we have all voluntarily ingested has a strange power, as if a messenger or a voice or something more, with which the taita is intimately familiar, guiding, knowing its demands, its energies, its rhythms, its ramifications.

More people filter back into the room, a developing circle filled with copal smoke and rhythmic chanting, an aggregation of souls, a small community of warmth returned as if guided by a collective impulse or understanding, the yagé, working with the taita, pushing us in a different direction, one of shared feeling and energy: the ceremony has shifted: suddenly we are all palpably together, looking around the room, at each other. I am moving away from death into the pulse of a breathing circle, and if I am a pile of dried bones I am still part of this fellowship. The taita gets up from behind the altar table in full regalia, headdress of colored feathers, and begins a strange beautiful dance, playing his sad dissonant harmonica, the dried seed pods around his ankles a rhythmic cascade of sound and energy rising in intensity until we are absorbed in his performance, or whatever it is, not a performance but a gateway, an entrance, into something else.

Suddenly, jarringly, the door bursts open with two men carrying a large, heavy, inert form as people move instinctively to prepare a mat and it is laid gently down, all of this as if choreographed, the body, thing, creature, whatever it is, very strange and shocking, as if some physical, amorphous manifestation of human suffering, moaning softly as another person enters behind them and places a blanket over it. This animate mass, now crying and writhing in pain, instantly galvanizes everyone’s attention. The sudden almost violent entrance of the body and the people around it has shattered the contemplative bell jar of shelter and connectedness I have been feeling, wrenching me and everyone else in the room from one state of consciousness to another with the flinging open of the door and the urgent sense of crisis, as if we are intimate observers in an emergency room drama, a critically wounded patient rushed in and hurriedly placed on life support, a deadly serious coordination of movement and energy. It takes several moments to register but now I see it is the younger woman of The Two Who Are As One who is on the mat crying and moaning, and it is her older partner, in her thirties, a baseball cap over long black pony-tailed hair, who has placed the blanket over her lover.

Now all attention is focused on the young woman lying in the middle of the room, midpoint in a circumference of energy, the taita dancing towards her, her distress increasing as she cries out, her body twisted in a physical manifestation of psychic torment, suffering and pain of a troubled past—sexual abuse and gratuitous cruelty, how can I know, really, but the sense of it is very strong. The shadows in the room are such that I cannot see her face clearly, and for a moment her shadowed form conveys the terrifying impression of a writhing lump of human suffering, a sack of thick, venomous serpents, but the feeling dissipates as the taita dances around her, the pace and intensity of his ancient movements building in urgency, the rhythms, the odd shuffling dance with the shells around his ankles, the harmonica, the long colorful healing feathers brushing the suffering woman along the length of her body, cleansing, soothing, caressing. The taita’s rhythm is taken up around the room, all of it concentrated on the woman, some looking at her, some focused internally, all of the energy directed towards the center of the room. The taita’s son circles with the brazier, fanning the smoldering copal, the rhythm intensifying, the woman moaning, crying out, people moving their heads, bodies, in time with the rhythm. The other of The Two Who Are As One moves slowly towards her partner, now kneeling, next to her, tentatively reaching out, touching a shoulder, the taita blowing his harmonica almost furiously, the woman groaning, twisting, her face dark, eyes closed, mouth open, calling out, pleading. I am clapping my hands with my fingers spread, a popping sound, in rhythm with the taita’s dance. Every ounce of my concern and compassion is directed towards the young woman. I am with her completely, through the taita. The energy in the room is extraordinary, almost ecstatic: the single most important thing in the universe at this moment is helping this woman. Nothing else matters. I have felt this concentration of healing energy before with my children when they have been sick, but the collective energy here is something I have never experienced. Her partner moves closer, caressing her lover’s arms, adjusting the blanket around her. The Two Who Are As One are moving closer, the taita dancing away, turning his healing energy to others in the room. I am fascinated, watching the couple come together, an archetypal journey of separation, trial, and rejoining played out before me. At the same time I am aware of the taita in the background as he stands over each of the others in turn, dancing, playing the harmonica, brushing with the feathers. When my turn comes he stands over me and performs his ritual. He has become something other, this man who appears so ordinary in everyday life, now transformed into a being possessed with a strange power. I am participating in an ancient ceremony. I am no longer in regular time and place. I am a thousand years in the past. I look up into his dark face, into his eyes, and offer a humble “gracias.” He sees me, but at the same time he is somewhere else. He moves on, back to the table, the energy in the room, having reached a climax moments before with the woman, gradually subsiding.

The older of The Two Who Are As One is now sitting next to her partner, pulling the blanket higher, whispering softly, stroking her arms, moving closer, more intimate, a process of re-merging. Now the younger woman’s head is in her lover’s lap. I am staring at them, marveling at this animal movement, a kind of natural belonging I have never seen before, but so remarkably ordinary, so correct, so obvious an aspect of human relationship that I have the dual-feeling of the ordinary and the profound together, of something I have seen and understood all my life but now for the first time revealed. The older woman is stunningly beautiful, calm and deep as a vast, dark lake. Everything about her is female perfection, her beauty, her palpable strength, her assured, relaxed nurturing, her sexuality. I am awed, overcome with her, overwhelmed. If I could have any woman in the world it would be this one. Her sexual orientation is of no importance. She is the woman, all women, and here crystallizes something else central to my being, the sad, dysfunctional course of my life’s relationships with women, how I have resisted and fought them, attracted and repelled, loved and hated, all of it going back to the sorrowful, alcoholic, frustrated life of my own mother, drunk and dead at 33 in an automobile accident the night of a hurricane, escaping for the last time, her children left behind in a motel room.

Death, my own, the death of my mother, the troubled lives, mine and hers, the repercussions, a chain of folly and suffering, false beginnings and catastrophic ends, illusion and ignorance. I see now with bone-shaking clarity (but I have known this all along) the greatest blindness and lack of my life has been the woman, the mother, and from this, relationship, the merging of disparate parts, the urge to completion, to become whole: The Two Who Are As One. The woman, her partner’s head in her lap, looks at me and smiles. I have been looking at her intensely but I don’t know if I return her smile. Nor do I know what we have communicated. But I do know with certainty that all comes from the female, the mother, foundation and nurture, that losing touch with this is losing touch with life itself. I know what I have lost, really never had, but something has kept me going, perhaps the longing to fix for myself the broken circle (from which I also rebel) of relationship, man/woman/god/nature/community, sundered by human folly, its vices and distractions, greed, aggression, the lust for power, the ascendancy and glorification of these impulses in codified patriarchal social relations. Come Back! I have screamed my whole life, to my mother, myself, others, in virtual incoherence, a wavering trust in my instincts, never quite sure what it is I have been screaming about, a vague image of something broken, myself, certainly, but not only me, more, surely more.

And what I see now in this little circle of fallible, half-broken human beings, myself included, is that, for me at least, it has derived, this brokenness, from the lost and crippled mother, the mother I never had, and that most of our tragedy and dysfunction stems from some sort of similarly profound disconnection, whether it be from a parent, a family, or a community—or all of it. A cosmic no-brainer! I laugh. The woman looks at me again and smiles. This time I smile back. She is a marvel and I love her, all women, and now I am crying, the tears spilling out, I can’t help it, nor do I try. Jesus! I say in a loud whisper, shaking my head in wonder. Jesus! And this word, Jesus, as will happen, one thought leading to another, yagé or no, connects me with the old boy himself, who, as the story goes, understood our tragedy and suffering and offered himself up as object lesson, hoping some day we might have the wherewithal to understand just what the hell he was talking about.

As the spirit of Christianity is in the ceremony, the historic Catholic (invasion/plunder/fanaticism) influence on the indigenous culture, it is perfectly normal, it seems to me, to dwell on the message and meaning of Jesus. It is not something I’ve done much of in the past, indeed have looked upon the hypocrisy and corruption of organized religion, especially Christianity, with its message of peace and love, with particular contempt. But the message of Jesus gets buried in the glitter and garbage of human perversion and stupidity, as he surely knew it would, and I wonder what he was thinking as he took his last agonized breath, “Father, forgive them,” no different from the Buddha or any other profoundly wise person having a clear handle on human nature: the obdurate reality of our lives, if not essence, being suffering, continuing thus, “for they know not what they do,” until we get it right.

The Two Who Are As One are fully together again, the rest of us returned for the moment to our strange internal worlds, everything slower, energy settling, the rhythm and dancing stopped for the time being, the taita and his son behind the table quietly talking, laughing softly together. What they are saying is a mystery, slightly demonic duendes, chortling Hopi Koshares (for a moment I see their striped bodies), other-dimension spirits, feathers, rattles, dark skins, strange murmuring tongue, arrived through a trapdoor opened briefly. Everyone here is out of their mind, inmates in a special asylum, a journey into non-sanity, licensed to act out, talk with our demons, caress our fears and our loves, vomit our insides all over the ground, spew our poison, the earth transforming and nourishing.

How much time has passed I have no idea, but certainly it has been hours. I feel nauseous and fight the urge to go outside and throw up. Slowly there is a change in the atmosphere. I have the sensation of being in a hotel room and outside, connected to the room, a lounge where dozens of people are gathered, socializing and drinking cocktails, a strange libidinous energy, a laughing, wolfish noise growing in intensity, a howling followed by a raucous, simian uproar, two creatures screaming at each other, back and forth, disturbing my inward thoughts and reflections. Who can it be? By the sound there are at least a dozen people, but this is impossible because there are that many in the room, our full company. The careful contemplative nurturing of my insights, thoughts of harmony and connection, are replaced with agitation and anger. How quickly things can change! Who are these self-indulgent, disruptive creatures? What sort of frightening, disharmonious energy is this?

The door flings open and Duván, in a blood-red serape, steps into the room, hunched over, an apparition, a demon in some kind of whirling, hopping dance, odd dreamlike movements, hands curled into claws, his face an animal grimace, stalking, sneaking, growling, searching, the taita from behind the table beginning again with his rhythms and harmonica, everyone focused on this new direction/dimension in the fabric of our collective, one of us transformed to something other, not quite human, something animal-spirit, a force, a shift in being, Duván/not Duván, untethered, roaming the audience, confronting, forcing himself into our consciousness, some kind of threatening, aberrant, whirling dervish, the taita and his son accompanying him with their rhythms, Nico, too, appearing, beating some kind of drum, Duván’s feral, twisting form emitting howls and strange nonsense sounds, one sound-word riffing off another in a bizarre stream of creature consciousness, inarticulate, frightening. Something obviously weird and extraordinary is happening here, at least in my experience, but maybe things like this are common with yagé, an open door to a different dimension, like art, or theater, or therapy. The medicine has granted Duván full passage to behave in this extraordinary manner in front of everybody and no one is particularly disturbed, taking it all in stride, at least so it appears, and my hostile reactions to the screaming wildness in the hotel lounge outside have given way to observing and absorbing this phenomenon who is my friend, now something other, contorted, hopping, leaping, and lunging around the room like an angry troll, but I know Duván and he is neither demon nor troll and I am not afraid of him but interested in his movements, as if I were watching a dance performance, and it is not that much different, though on one level, owing to my state of consciousness and the unusual context, what I see is a mystery and not Duván but something entirely alien and marvelous.

It goes on for thirty minutes, longer, this wild, angry spirit prowling the room, striking out, howling, aggressively imposing himself and his emotions on us, and I begin to wonder at last how long I can take this, how long he can take it, his energy apparently boundless, at last the taita and his son gradually ceasing their rhythmic accompaniment until it is Duván alone, finally, somewhat reduced and vulnerable, solitary, the weave of the room returning to its introspective, unitary fabric and Duván, too, returning to the group, still talking to himself, still possessed, but whatever it is that drives him dissipating, and he is suddenly exhausted and slumps down next to me, putting his head on my shoulder.

Music comes from the speakers, random movements around the room, shifting positions, some people lying down, slipping into yagé middle-world, the intense healing session with the suffering girl, Duván’s madness, the wracking physical and psychic ordeal with the medicine, the utter strangeness of everything. It must be getting towards dawn, Duván, still with his head lolling on my shoulder, a rolling, meandering stream of consciousness, occasionally rising in intensity and anger, but settling gently, with humor, nonsense words striking us both as absurdly, poetically funny, the rubbery, bending, looping genius of language, and the motif, the sound and feeling-chant, yagé, yagé, yagé…hey-yah, hey-yah, hey-yah…this new friend of mine, brother and son, we are very close, laughing together like a couple of old companion-drunks after a night’s binge, the consciousness of self and place returning, a signal the medicine is wearing off, but still strong and strange as we watch the taita walk around the room, headdress removed, the music softly emanating from the speakers and then a shift to a new, more powerfully rhythmic, brilliant sound, as if a wake-up signal for the collective, though no one stirs, Duván and I both aware of the new musical energy and alert to the change it portends, the taita pulling his cell phone from a pocket and talking, Duván and I having heard the change in music and anticipating a new direction in the ceremony and realizing together the source of the new music as the ring-tone from the taita’s phone, and we laugh, and of course it does mark a turn in the evening, a nice touch of absurdity to make things sensible, all of it a great big marvelous joke.

A light goes on in a side room, a bustling of concern, the taita, having put away his phone, involved in a serious conversation with some of the participants. Duván has returned to his place across the room and is lying down. Everyone is settling into a quiet resting state. I lie down on my mat. The conversation has subsided, whatever the concerns, apparently resolved. The taita is talking to the older of The Two Who Are As One, and they are laughing. Her companion is sleeping.

I am tired and want only to pull my sleeping bag over my head and rest, go to a different world, but there is one more part to the ceremony. The room is slowly brightening with dawn. The taita’s son sets a chair near the altar table and beckons to one of the participants, the young man who had come in the same time as The Two Who Are As One and has spent most of the night lying down, seemingly sleeping. He removes his shirt and sits. The room is chilly. The taita starts his chant-song and dancing, interspersed with the harmonica, and performs a cleansing ritual on the young man, copal smoke, brushing with feathers, taking what looks like dilute yagé into his mouth from a bottle and spraying all along the man’s body and in his hair. Then he draws in with his mouth the bad spirit-air from the young man and exhales sharply, expelling it. There is an informality to the ceremony, the taita talking and laughing with his son throughout his ministrations, lending a curious air of legitimacy, as if the taita was so mechanically practiced, the ritual so certain, that only a portion of his full attention is required, as if he is changing a tire, shooting the shit with a co-worker. I am exhausted and strangely ego-diminished, as if only a small, vulnerable portion of me remains. This last cleansing ceremony is the completion of the circle and one is expected to participate, but all I want is to bury myself inside my sleeping bag, to disappear, sleep, recover from the night’s tumultuous journey, the catharsis and the ordeal. But there is no hiding. The taita’s son, who is now performing the ritual, comes to get me. I remove my shirt and sit in the chair, abandoning myself, as he completes the last part of the ceremony. And then it is over. I return to my sleeping bag and fall into a restless sleep for several hours, finally rising and joining my companions outside who, except for Duván, I have only known for a short while but nonetheless are as old friends. They talk about the night, exchanging experiences, visions, insights, laughing at the sheer power and profundity of the ceremony, but when they ask me, all I can do, partly because my ungainly Spanish inhibits me from expressing the nuances and strangeness of the experience, and partly because I am still overwhelmed, is smile and shake my head.

The rest of the day, and that night, we recuperate. A nice bond has formed, a sort of fellowship. The next night another ceremony. I am sicker, throw up three times, much of the evening preoccupied with fear and its insidious nature, how it cripples and inhibits us, how we can understand it and transform it. The rugged ceremony, with the powerful tigre, is a passage. There is a crystal bush that becomes a sentient being, something like a deity. Fear slides into eroticism. My ego disappears. I am nothing. There is another suffering person towards whom, at the height of the ritual, the taita’s and group’s energy is directed, this time a young man with some kind of neurological condition. He is laid down next to me, his leg twitching uncontrollably. I put my hand on his leg to stop the movement. The taita notices and says something to his son and they laugh, Hopi Koshares again.

The following day I get on the bus and return to Quito, back to the normal life. Nothing I thought about during the ceremonies was particularly revelatory, having spent a lifetime thinking about these things, but I am slightly changed. The feeling of the yagé stays for many days, I am more conscious of the connectedness of things, more compassionate towards the milling masses of hurrying, preoccupied people in the streets. I am humming softly to myself: hey, hey, yagé… And there is something else that I have thought about often, an old realization to be sure, but now supported with an extra degree of conviction. There are elements of indigenous culture throughout the world, which we with our technological arrogance and stupidity regard as primitive and backward, that have nothing less to teach us than the essence of what it is to be human, in the best sense of that fraught and enigmatic word. These cultures continue with their ceremonies and traditions, their unique perspectives, regardless of what we do, in most cases mildly tolerant of our eccentricities and failings, patiently willing to teach and share, even as we decimate them and their physical environment. There are no answers to Gauguin’s questions: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? But those still practicing the old ways have some suggestions. Who among us is listening?

March 03, 2015