I've been taking pictures since I was a small boy and have always been intrigued by the process and art of photography. Since using my parent’s Kodak Brownie I felt the magic of snapping shutters and recording what was in front of them. While in college I saved my money and bought a 35 mm camera and began a life-long love of the photograph. I even learned how to work a dark room. Then I began shooting film, super-8, and later 16 mm motion pictures. Following Sony’s introduction of the Porta-Pak, I was hooked on the immediacy of video tape and have continued until the present to be a “videographer.”

Photography, arguably the most important development in the plastic arts, was a dream come true for western culture since the Greeks amused themselves with the camera obscura. The art of cinema, which is after all the placing of one still frame after another – twenty-four of them each second – tricks the brain into seeing “motion,” and is a mechanical extension of photography. The only true advancement came when Edison punched sprocket holes in the film, allowing for more stable flickering on the screen. Everything else – sound, color, widescreen, 3-D – is a mere technological development of what is at bottom millions of still frames seen in rapid succession.

In the 175 years since photography has been in existence, since the great Nadar opened his Paris studio, and Mathew Brady set up shop in Washington, D.C., practitioners of camera art have been at work documenting the personages, land- and city-scapes of their eras, offering us a format to capture the long-gone persons and vistas of their eras for all time.

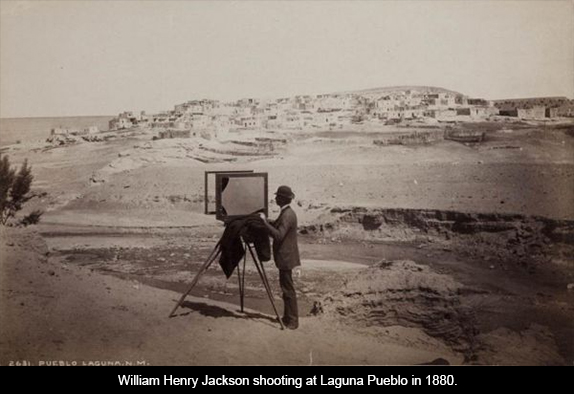

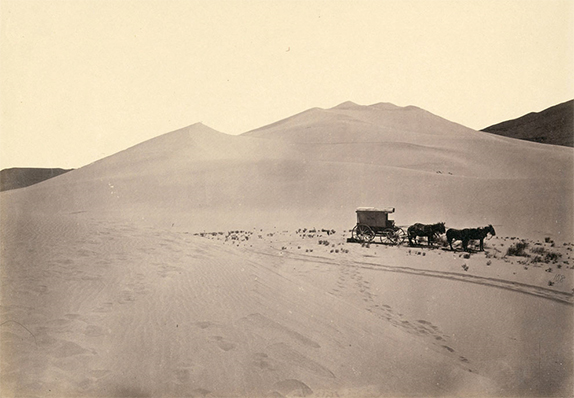

New Mexico began attracting photographers as early as 1847, just one year after the U.S. wrested the territory from Mexico. The nascent images of William Henry Jackson, Timothy O’Sullivan, F.J. Haynes, and William Bell, brought a new awareness of the West into the public’s view. These men were pioneers in the field: Jackson astounded the photographic world in 1875 by packing a camera for 20 x 24-inch glass plates up the Rockies; O’Sullivan photographed our natural wonders, in 1871 ascending the Colorado River into the Grand Canyon, then making what are considered his finest images, capturing the awe-inspiring Canyon de Chelly in Arizona. Haynes became known as the “Official Park Photographer” of Yellowstone. In 1900 he produced the first set of picture postcards.

In 1867 O’Sullivan made the photo below of his traveling darkroom on the Carson Desert in Nevada, showing the tenacity of these early photographic pioneers.

In 1917 Mabel Dodge Sterne (later, Luhan) began inviting artists to her “desert salon” in Taos, among them Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. Instantly they realized the wonders of the place, especially the magnificent light. Adams thought it was very beautiful and magical – “…a quality which cannot be described.” Then he spent years trying to capture that quality on film.

In 1941 Weston returned to New Mexico and made a series of pictures of White Sands, that sea of gypsum where the nuclear age began, which has captured the attention of so many image makers. Weston, true to form, added female forms to those shifting sands. Willard Van Dyke, one of Weston’s assistants, later made a film about Weston, The Photographer, still worth seeing.

In 1930 Ansel Adams and his wife spent 3&1/2 months in Taos, while staying at Mabel’s, and produced one of the first professional books of photographs of the Indians called Taos Pueblo. The book received high praise and established the photographer’s style, coupled with Mary Austin’s strong prose—it was a big hit.

Adams never resided in New Mexico, but his iconic photographs of our Spanish churches and Indian Pueblos became known the world over.

Other work that brought him to this state was an assignment from the Department of Interior, the U.S. Potash Company near Carlsbad, and a commission for a dozen color images for Standard Oil. It was on one of those photographic expeditions that he snapped what is one of his most famous shots. Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, was taken while returning to Santa Fe late one afternoon when Adams looked in his rear view mirror, and there it was. He stopped, set up his camera, and voila, f/32 at 1 second.

In their beautiful and insightful book Photography: New Mexico (2008), Thomas Barrow and Kristin Barendsen, explore the works of contemporary photographers like Barrow, Paul Caponigro, Delilah Montoya, Miguel Gandert, Betty Hahn, Jim Kraft, and the late Douglas Kent Hall. There are many others and their works span the gamut of techniques, from abstract expressionism and minimalism, to documentary realism, portraiture, landscapes, quotidian details, and the fantastically haunting multiple images of Victor Masayesva, Jr., a Hopi who has breached the forbidden barrier into American Indian life and rituals.

This is to say nothing about Joel-Peter Witkin, an Albuquerque-based artist who produces grisly, historically mimed reproductions of Old Masters, including one of the founders of photography, Louis Daguerre, whom he portrays as a corpse.

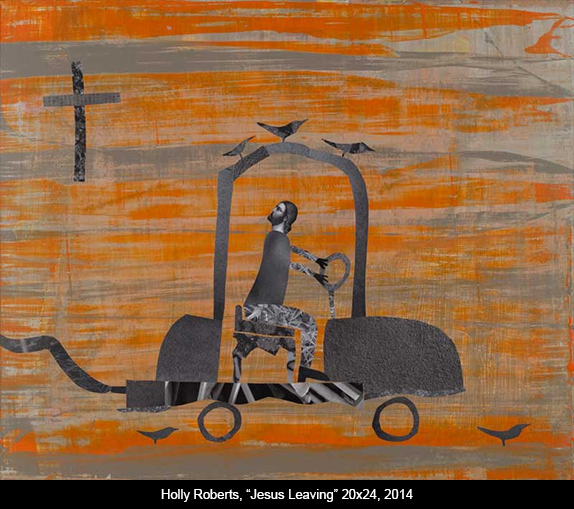

Or the abstract melding of photography and painting that drives the haunting images of Holly Roberts, a Corrales-based artist.

We are fortunate to have these pictorial artists among us, enriching our lives with their work, and showing us that New Mexico has the ability to nourish the creative sensibilities of artists who use cameras to capture their muse-driven images.

Hopefully, this will motivate you to seek out their work whenever possible; or even to pick up a camera (or iPhone), and express your own hidden visions.

[1] Whether Adams was working for the Department of Interior when he took this photo—thereby making it government property—or not is a matter in dispute. He made about 1,200 prints in his lifetime. In 2006 the highest price ever was paid at auction for one, $609,600.

May 27, 2014