The logic would seem irrefutable: The atomic age made modern New Mexico; Robert Oppenheimer was the man most responsible for making the atomic bomb; three women in his life helped shape the man; these women are important for us today to understand.

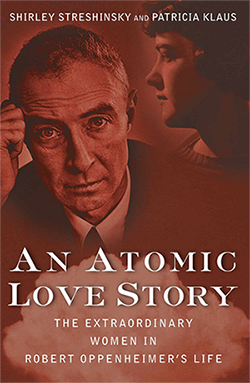

This logic led me to An Atomic Love Story: The Extraordinary Women in Robert Oppenheimer’s Life by Shirley Streshinsky and Patricia Klaus (Turner Publishing Co., 360 pages, $27.95), which was published in September.

Oppenheimer, this “elegant puzzle of a man,” led many lives, as a brilliant nuclear physicist, as a polymath who learned Sanskrit so he could read the “Bhagavad Gita” in the original, the first director of Los Alamos National Laboratory, the supervisor of the development of the first atomic bomb, and finally the most prominent victim of the red-baiting witch hunt of the vicious Republican senator from Wisconsin, Joe McCarthy, who made much of the fact that both Oppenheimer’s wife and mistress were members of the Communist Party. Oppenheimer is depicted in this book as kind and cruel, efficient and shambolic, brilliant and shortsighted, loving and hateful, faithful and treacherous. A physicist who knew him well, Isidor Isaac Rabi, a scientist as great as Oppenheimer himself, said Oppenheimer was made of splinters of a man that he was never able to integrate into a single personality.

Oppenheimer’s women were nearly as complicated as he was. All were people of high attainments and great ambition, especially notable in an age when the world belonged to men; all were many-layered and tortured.

His wife Kitty, a frustrated botanist, had been married three times before Oppenheimer and wrote to a friend that she got him to get her pregnant so they would wed; yet, they loved each other and remained together through the rest of their lives. Kitty, the authors say, was an “enigma.” “Bright, frustrated, capable of erratic kindness and frequent cruelties, she was the epitome of a life unfulfilled.”

Oppenheimer’s mistress, Jean Tatlock a clinically depressed but brilliant bisexual woman whom he continued to see long after he was married, was a medical doctor and a psychiatrist who died a mysterious death; some of those close to her believe she was drugged and drowned by a federal agent., Lt. Col. Boris Pash, who followed Oppenheimer around, tapped his mistress’s phone and during the war tried to deny Oppenheimer a security clearance. Yearning for an imaginary lover before meeting Oppenheimer, the young Tatlock wrote, “Were he a fine man, he could make something out of me.”

The third woman, Ruth Tolman, older than Oppenheimer but still attractive, may or may not have been Oppenheimer’s lover, but it was clear that this brilliant doctor of psychology was extremely close to him for many years. Married, she was often separated from her husband by work for long periods. “It was if you are running in a dream and your legs won’t move,” she wrote to a colleague during government service in Washington during World War II.

One of the many minor women in Oppenheimer’s life was Katy Page, who wrote to him that “one of the main functions of a heart is to ache.” She was murdered in her Santa Fe home during a 1961 burglary by a neighborhood youth.

An Atomic Love Story tells, in strict chronological order, the stories of the interwoven lives of the four fascinating principals. Each of them was also the center of another universe, so the book also becomes a study of the circles within circles that constituted the tiny elites of California, Massachusetts, New York, Washington—and New Mexico.

For this is also a New Mexico story. It was here that Oppenheimer grew from a shy, hesitant adolescent into a charming and domineering adult. It was here that he discovered the outdoors, riding on horseback for hours, even days, through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. So it was logical that it was here that he chose to develop the atomic bomb in a remote site in the Jemez Mountains.

As fascinating as I found this study of these four interlocking lives, I had difficulty following it because of the jumpy narrative strategy, forcing the reader to keep track in alternating paragraphs of the four principals—all with their own circles of relatives, friends, colleagues and lovers.

Yet this is a relatively minor quibble. The authors have done an extraordinary amount of research over many years. For them it was a kind of detective game, filling in lacunae in these four lives with old diaries and letters and new interviews, finding relatives still alive after a half century throughout the United states and Europe.

The book is a significant contribution to the peculiar field of women’s studies, which often perforce focuses less on women who changed the world than on women who changed men who changed the world, as is the case here—“women who are ancillary to the main attraction,” as the authors put it. Because of the nature of the subject, such books tend to focus on relationships, on love and sex and what these twinned passions do to and for those involved. Such is especially the case with “Atomic Love Story.”

The value of this book and of the relationships it plumbs was perhaps best described in the authors’ epilogue summary of Oppenheimer’s women:

“Each of the three in her turn helped shape his character, read poetry with him, opened doors to new worlds for him, took risks and laughed and entertained with him, encouraged and comforted him. They gave companionship and friendship and, most of all, the love that Robert Oppenheimer, aloof and arrogant though he could be, needed as much as any man.”

December 17, 2013