[ . . . ] the behavior, culture, language,

and social organization of rocks.

–The Onion, November 13, 2014.

Every so often I come across a book that is more than just a book. I know I won’t read it once and then relegate it to my personal library, where I may seek it out again at some point. Its contents—text and/or graphics—announce themselves as engaging in a way that tells me I will consult it often for wisdom, inspiration, or connection. The Lines (by Edward Ranney, with an essay by Lucy Lippard, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, 2014) is such a book.

What do we expect or want from books about ancient archeological sites? Simply a coffee table edition a bibliophile would delight in petting? An exquisite collection of National Geographic-type photographs that excite us to make a visit of our own? Often I am searching for information, and what I find is either superficial tourist propaganda or something so complex I would have to be an archeologist myself to crack the code. I knew I should have taken more math, I mutter to myself, as I grapple with passages for the fifth or sixth time.

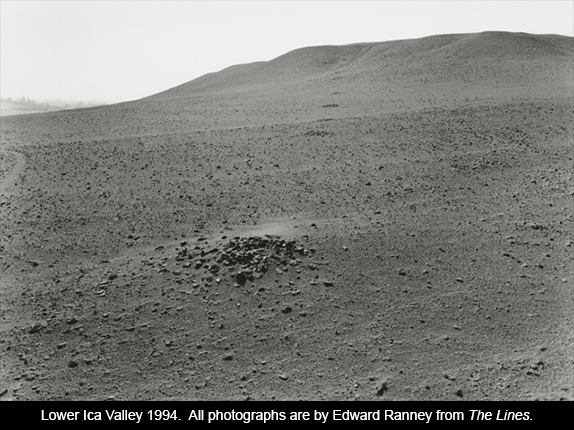

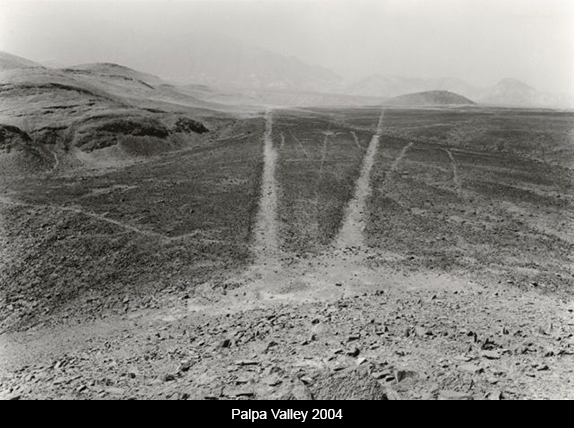

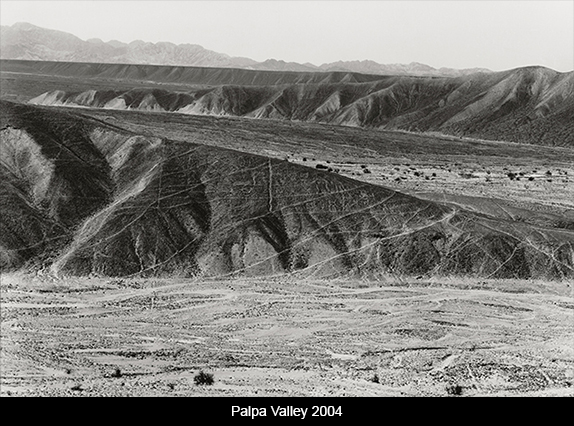

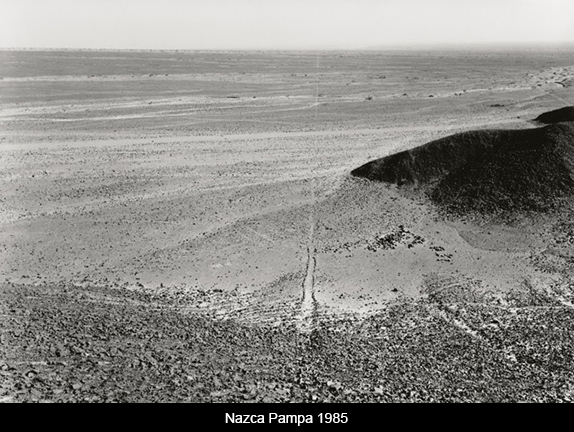

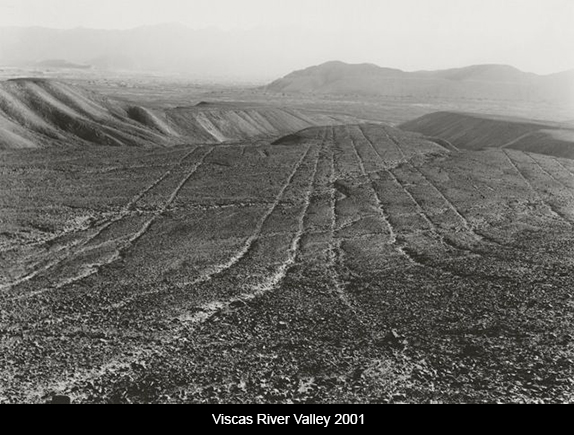

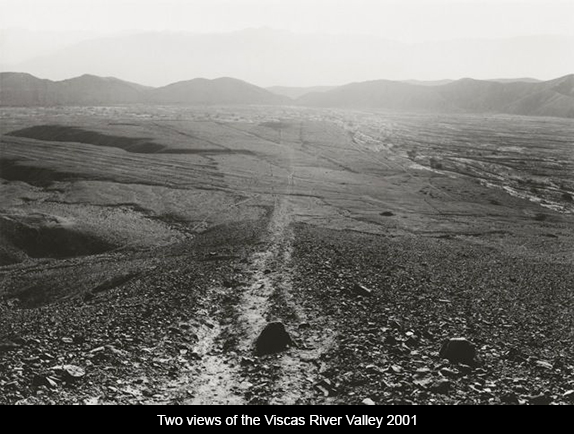

The Lines is none of these. This 10 x 11-1/2 90-page hardcover volume might not immediately grab the attention of someone browsing through a bookstore. This is because it is understated, immensely subtle, its front and back covers pale black and white images of a landscape most commonly photographed from the air but rendered here from ground level.

The famous lines and other land features of southern Peruvian valleys, created by the Nazca culture some 2,000 years ago although only discovered by outsiders in the 1920s, and similar large geographical features made by cultures on Chile’s Atacama desert to the south, have fascinated anthropologists and others for at least a half century. Aerial photography, with its intense contrast and larger than life aura, represented the Nazca Lines as if they had been made by supernatural beings on a canvas too vast to take in at the human level. Edward Ranney’s photographs in The Lines reveal a more intimate Nazca. In her essay Lucy Lippard tells us:

[T]he lines “are not invisible from the ground, (though [ . . . ] if you pass twenty feet to the side, they can vanish), but local residents who knew them may initially have been reluctant to advertise their presence. Their own oral histories would suffice within the culture, and “discovery” by outsiders was not necessarily desirable (though the modern economy has flourished with tourism and an astounding level of grave robbing).

Ranney and Lippard understand and transmit, each in his or her medium, the tensions between remnants of ancient cultures and the ways in which those cultures are perceived, used, and often abused by those who try to access their legacies. The Lines also includes a selected reading list of in-depth studies, for those who are interested in exploring the subject from several different points of view.

As I began writing this review, yet another multinational climate change conference was coming to a close in Lima, Peru. A December 14, 2014 New York Times article reported several members of Greenpeace having damaged a portion of one of the Nazca Lines by erecting a sign protesting the effects of global warming, an example of ironically poor judgment (some commented that Greenpeace needs better parenting). Being able to look at art and culture in a variety of iterations and in a many-layered way is one of Lippard’s great fortes, and her essay contemplates the contemporary issues surrounding Nazca as well as the work of many scholars who have dedicated themselves to interpreting the astonishing panorama.

This land art, for lack of a better descriptive term (applying our modern definition of art may be our first mistake), is about rocks and geometry. It is also about social organization, which is why I begin this review with a quote from The Onion, which for those who may not be familiar with it is a satirical paper that spoofs the news, often obliquely pointing up the absurdities in much of what passes for information today. This particular quote ascribes behavior, culture, language and social organization to rocks, an assertion that may seem ludicrous to some. The Nazca Lines, and this book that explores them in such evocative photography, make us conscious of the fact that despite its satirical intention The Onion may be on to something.

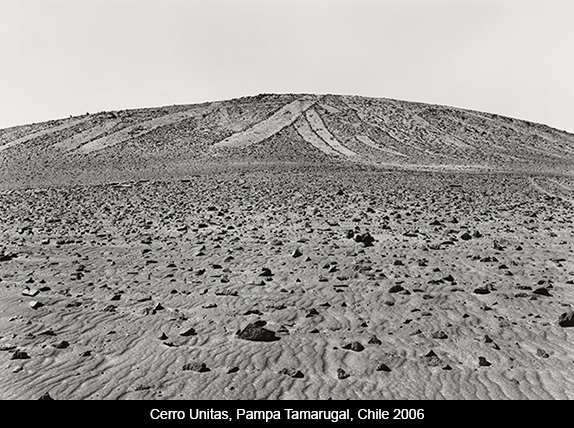

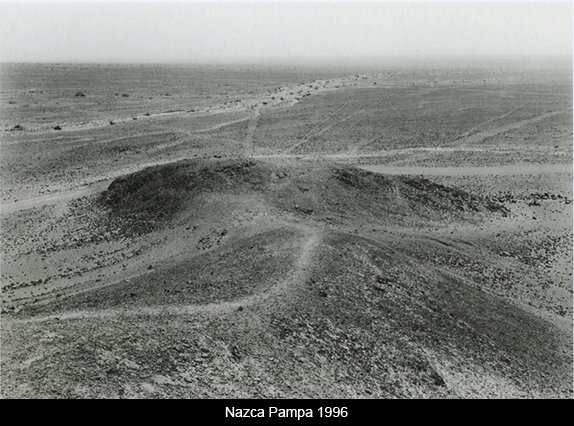

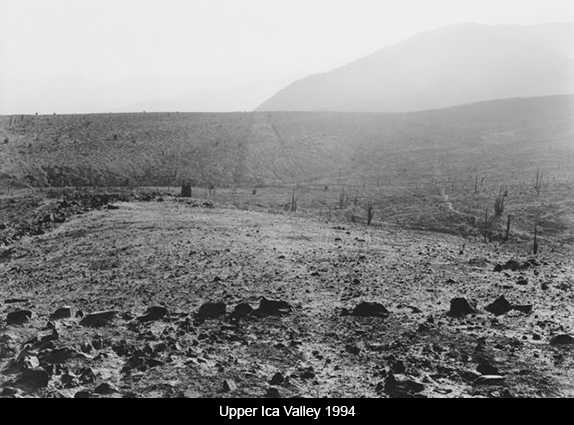

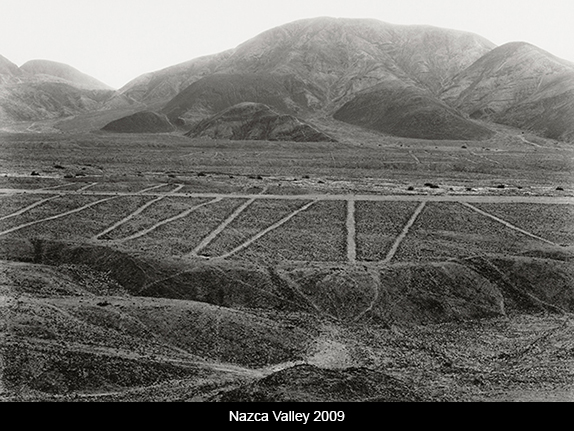

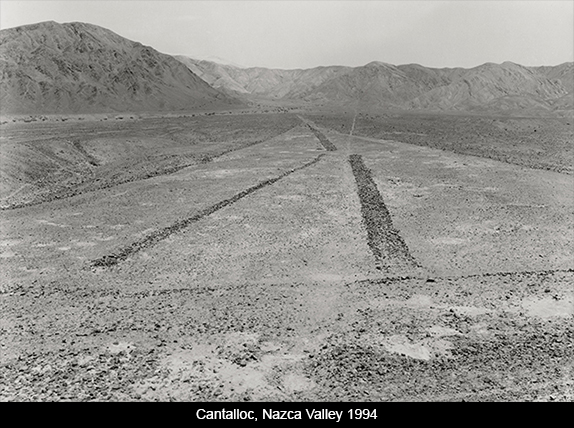

Ranney’s photographs, made on the ground from the elevations of surrounding hills and ridges, see the lines and biomorphs (symbolic, animal, and humanoid images) as those who created them saw them. Sometimes the photographer is looking up a valley, sometimes across. Many shots appear to have been made almost at ground level. In one he positions his lens from around the corner of a large foreground rock. Ranney’s meticulous large format detail is rendered in many tones of gray rather than the stark black and white obtained through digital or darkroom manipulation. One cannot imagine these images in color. In this and other aspects (angle, perspective, feeling), they more accurately simulate the high altitude landscape with its thinness of air and light. I can imagine gazing breathless at the places Ranney gives us.

Ranney has been photographing in Peru’s Ica Valley and Rio Grande-Nazca River drainage for thirty years, and on Chile’s Atacama Desert more recently. In his brief but deeply resonant introductory text, he says one of his particular interests has been “to explore how geoglyphs in different areas of the coastal desert occupy and alter space on ground level.” He sees the lines as “a form of mapping, marking reference points and connections within the landscape, thereby transforming a harsh natural environment into an understandable, even intimate cultural space.” Not everyone has the ability to go beneath the surface of maps, unearthing or even suggesting their secrets. Ranney has this kind of an eye.

The 44 photographs float unidentified, except by a number that can be compared to a list at book’s end, each on a white field slightly wider than it is high. These are horizontal vistas, as landscape tends to be when viewed by humans. Almost all the images are on right-hand pages, with the corresponding left-hand page left blank. Exceptions are six pair, printed facing one another. At first glance some of these pairs might appear to be panorama shots separated by the book’s spine. A moment’s assessment reveals they are not. This thoughtful placement is clearly part of the experience Ranney wants the reader to have, requiring close attention to the layers of meaning in the configuration of the rocks, lines, and figures themselves.

We study one image and note a low pile of dark rocks ceding to another and another along a line that moves away from the eye, unmarked by anything but themselves as they go up a gentle hill and over its crest. We see equidistant “roads” converging at a distant point. We take in a hillside crisscrossed by lines that appear to be as narrow as wild animal tracks; some rise straight up over mountainous terrain as if they had been drawn there with white chalk. We see concentric circles over a vast plain with a ridge of trees and mountains beyond. And we trace curved as well as straight lines, outlining what may be immense figures in communal movement. There are fields of complex mazes, like labyrinths to be walked by giant beings. And there are great figures, their intricate designs produced by a clearing of topsoil and preserved through the centuries in a region where it rarely rains and there are few trees.

Lippard begins her brilliant essay observing that: “The ancient world continues to throw up surprises for today’s purportedly advanced civilizations, in the process exposing the limitations of our own Eurocentric views and expanding the potential of nature as mentor.” Nature as mentor. This sets the tone of a text in which Lippard makes her case with the combination of cultural sensibility and political insight we have come to expect in her work.

Early on she assuages our curiosity as to how this land alteration was made: “[T]hey were created primarily by a subtractive method, scraping away the black rocks covering the pampas’ pinkish ‘desert pavement’. (Some earlier glyphs were formed additively, outlined with stones, and a few combine the two methods.)”

The Nazca Lines and neighboring forms have their origins from around 400 years before the Christian era to approximately 1,500 years into it. They were conceived of and executed by an agricultural people who, despite considerable study since the 1920s, are not thoroughly understood. We know they developed a sophisticated system of underground aqueducts to deal with the paucity of water. We know they produced beautiful ceramics, and weavings reminiscent of their Paracas ancestors. The Spanish decimated the Nazca culture in 1532, as it did so many thriving societies. The Nazca left no written language as we define that, although the lines, the older Paracas textiles, the ceque system (what Bernabé Cobo called “a tactile form of language”), and the quipu way of recording events via series of knots on cords, may all be related in one way or another.

Lippard’s essay is titled “Above and Beyond the Straight and Narrow” and here, as in all her work, she asks important questions, explores answers using a wealth of scholarship and considered in terms of possibility rather than certainty, and goes beyond the subject at hand to offer thoughtful extrapolations for our current concerns: ownership of time and place, how we inhabit space and how we walk its limits, voice as expressed in the modification of landscape, climate change, environmental degradation, commercialization and marketing, how we might return to practices that safeguard our better selves, and the ways in which communities draw on cultural capital to find our way out of economic and social distress.

What values are expressed in the Nazca Lines?

Lippard asks: “Why straight lines?” and explains: “straight and crooked pathways render very different experiences of place.” As I read this essay, and this happens to me more often than not when reading Lippard, I felt like she was always one step ahead of my own thinking. Her discussion of straight lines that do not snake or switchback up mountainous terrain but climb straight over geographical impediments, made me think of the Chaco roads of the US American Southwest. A sentence or two later Lippard was making the same connection. I wondered about a possible link between the phenomenon depicted in this book and rock art that served as terrestrial or celestial landmarks in other cultures. A paragraph farther along Lippard addresses this subject in her consideration of the Peruvian creations vis a vis the pictographs and petroglyphs found at Ancestral Puebloan sites and others. I began thinking of twentieth century land art by such as Walter De Maria, Andy Goldsworthy and Charles Ross. Immediately, Lippard brought their work into her conversation with the reader.

English land artist Richard Long created “A Line Made by Walking” in 1967. Long walked back and forth in grass, leaving a track that he then photographed in black and white. The work balances on the fine line between performance and sculpture. About this piece he has written that “walking – as art – provided a simple way for me to explore relationships between time, distance, geography and measurement.” This piece might have been inspired by the lines and figures engineered in ancient Peru by the Nazca people. Or perhaps it was compelled by some modern day version of a similar need.

It seems to me that the most important distinction between the Nazca Lines’ alteration of landscape and those alterations produced by twentieth century artists is that the former worked in and for their community while the latter make individual, albeit often beautiful statements. Sometimes, as in the case of Goldsworthy, the artist intends a natural dissolution of the artwork: time and weather will destroy the piece, which remains only in photographic memory. Sometimes, as in the case of De Maria, the artist’s statement alters the landscape in a more permanent way. At his New Mexican Lightning Field a large grid of stainless steel poles irrevocably alters the landscape of a small valley; De Maria imposes his notably phallic ownership on the land.

The Nazca lines could not be more different from these and other examples of contemporary land art. Their construction obviously required group cooperation, but it is likely that people worked together on equal terms rather than in the rarified air of an artist’s studio (often with the help of paid or unpaid assistants), or indentured or enslaved as was true of those laboring to build the great pyramids or cathedrals. Although we cannot presume to understand what motivated Nazca’s creative effort, we can see that it responded to a worldview unlike what dominates today’s consumer culture.

As Lippard points out, “The deliberate loneliness and isolation of contemporary land art appropriate the forms of ancient cultures while simultaneously disregarding their values and belief systems. The ancient models were actively communal . . .” She quotes artist Robert Morris, “writing firsthand about the Nazca lines and Minimal art in 1975, [as defending] his contemporaries’ lack of interest in communication, [and] describing the then-new art as explorations of ‘the space of the self.’” What could be a more self-involved use of landscape? Neither were the Nazca lines and glyphs labor intensive like the pyramids and cathedrals or the monumental architecture we see at Machu Picchu and other Inca and pre-Inca sites throughout Peru and Ecuador.

Lippard explains that Nazca wasn’t a state society, and “centralized leadership and a labor pool were not required to make the drawings.” She quotes John Reinhard’s speculation that “they may have been constructed by small groups during slack periods in the agricultural cycle.” Yet their vast size and reach, the profound ways in which they altered the landscape for their creators and continue to alter it for us today, speak to a vision of immense proportions. The “Atacama Giant” photographed by Ranney, is 377 feet high and a line of llamas 246 feet long. Many of the Nazca lines go to the horizon, and the photographs in this book make us feel that they continue beyond it. This was community, communication, a way of conversing with place and preserving memory for those who would come later.

Ranney’s photographs are deceptively matter of fact yet haunting. They seem to breathe on the page. Lippard draws on the observations of chroniclers, anthropologists, ethnographers, astronomers, historians, artists, and poets for clues to the nature of these lines and glyphs, the why of their conception, the possible meaning in the communal activity required for their construction, and their significance for the people who made them part of their landscape as well as for those of us today who believe they have something to say to us. She explores directionality, seasons, kinship, and collective memory. She gets us pondering ritual, signage, and identity. Together, photographs and essay open a window to human alteration of landscape that is both majestic and pertinent.

December 25, 2014