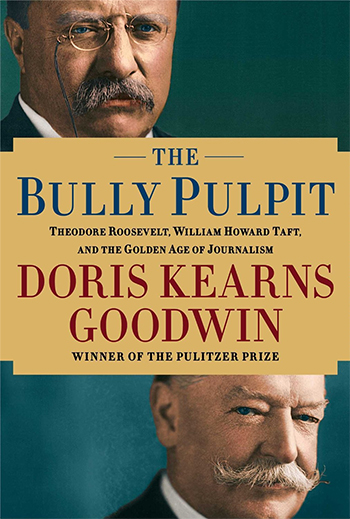

I couldn’t put it down even though it was a heavy lift. For the past month I have been lugging around the 900-page Bully Pulpit by one of my heroes, Doris Kearns Goodwin. Her account of Teddy Roosevelt, William Taft and the Golden Age of Journalism (the book’s subtitle) makes a great counterpart to today’s gilded age—and that’s why I read it. One hundred years later—are there any lessons we can learn?

First, the amazing similarities—the near total control of giant corporations, the unchecked trend toward mergers and consolidation, a gap between the rich and the poor, an unquestioned laissez faire philosophy, “a government network of legislators, bosses, and party leaders answering to the state’s major industries,” and a COURT captured by corporate interests.

Another similarity: a Republican party that was largely beholden to few wealthy captains of industry and powerful party bosses in select states, but which had a renegade faction pushing for reform.

Then: the differences:

-A muckraking press led by McClure’s Magazine, and a group of investigative journalists-- Ida Tarbell (a woman no less!), Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker and others.

- The leadership and personal popularity of Teddy Roosevelt who used his friendship with the press (the Bully Pulpit) and his brash style to take on the powers that be—especially Tammany Hall in New York and Republican Party bosses. He had plenty of opposition from Congress, yet he was able to drag it screaming and kicking to create a system of national parks, enact anti-trust legislation, ban contributions from corporations, and get civil service reforms. The fact that he was a liberal Republican from the upper crust was key. It was an era when the Democratic Party was aligned with the South and divided by progressives from the West and mid-West. TR’s suicidal, egotistical drive to seek the presidency under the banner of a third party (the Bull Moose Party) pushed the entire political axis to the left, ultimately resulting in the progressive reforms we know today: popular primaries, direct election of US Senators, a graduated income tax, disclosure of campaign contributions, inheritance taxes and many others. (TR’ sword rattling, imperialistic foreign policy was largely bypassed in the book)

These differences sketch a roadmap to reforms of the system in the 21st century.

The huge shifts in media production and consumption have been seen as a death knell for old style print investigative journalism. But it ain’t necessarily so. Locally, I’ve seen a new generation of independent, data-driven, techno-savvy news hounds. They need to be supported by someone like Sam McClure (crazy as he was), with broad new outlets for their work, and new models of reporting. The progressive era’s secret was the alliance between the press and public officials—now somewhat unimaginable. “In order to battle this entrenched system, it was necessary to instill something of his own sense of outrage in people to popularize the reformist cause and foment change from the bottom up,” says Goodwin. Roosevelt knew how to play the outside game, corresponding with journalists, inviting them to the White House to chat. And journalists like Ida Tarbell played ball. Always sticking to documentary evidence, Tarbell concluded “…it was not long before I was saying to myself as I had not for years, ‘You are part of this democratic system they are trying to make work. Is it not your business to use your profession to secure it?’”

Tools like IPRA and other transparency laws make this even more possible today. Organizations like Pro Publica, the Sunlight Foundation, The Nation Institute on Money in State Politics, the Santa Fe Reporter, and NM In Depth are leading the way. Mainstream media and the outdated idea of “objectivity” are guarding the pass.

Courageous—even foolhardy—leadership that was willing to break ranks and antagonize the vested interests was a key part of the progressive era. Yet, today’s political system breeds anything but courage. With occasional lapses, political leadership—the stuff of Profiles in Courage—is now inoperative. It has been replaced by something different. It is defined by the ability to raise money, evade controversial issues and political risks while projecting a warm positive image. I say this as a 16-year legislator, who saw few examples of real leadership in Santa Fe.

So then, how do we create courageous leaders? One suggestion is to reward courageous acts and those who take risks to change the system as a whole. Praise NM Senator Tom Udall’s efforts to amend the constitution to address Citizens’ United (Teddy Roosevelt, in his Bull Moose stage, wanted the people to have the right to recall a judicial decision if they thought it wrong, especially when half the judges decried the outcome), support Rep. Emily Kane and Sen. Bill O’Neill’s drive to open primaries to independents and create independent redistricting commission, and give Janice Arnold Jones credit (retroactive) for opening up legislative proceedings on the web.

Prolonged economic depression here may in itself create new leaders among a generation that is thrown back to part time work, scrambling for education, and now using their entrepreneurial instincts to create networks, to survive.

I am looking for other suggestions on how we create courageous leaders. It’s an important mission. And I am also looking for a solution to what Lincoln Steffens called in that era, “The twin stupidities which dull the conscience of America: the optimism which says that all is so good that nothing else needs to be done, and the pessimism which says that all is so bad that nothing can be done.”

If you have any ideas, or would like to join a 21st Century Salon to discuss the Bully Pulpit let me know at .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address).

September 10, 2014