Editor's note: This is an abbreviated version of a report prepared by Darcy Bushnell for the Utton Transboundary Resource Center.

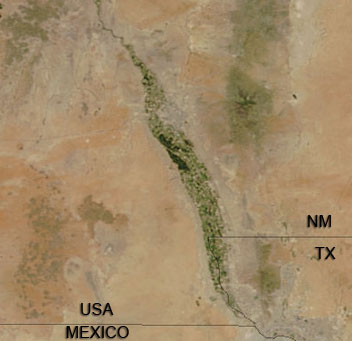

(The N.M. Lower Rio Grande Valley, Courtesy of NASA/Visible Earth)

Texas wants to sue New Mexico in the U.S. Supreme Court over Rio Grande deliveries. This article explains why Texas chose the Supreme Court and the criteria it must meet in order for the Court to accept the case. It also lays a foundation for an understanding about why Texas and New Mexico are at odds over the river and its water.

To do so the article provides background about the Rio Grande Compact, the Rio Grande Project, and the efforts made by the States and individuals since the late 19th century to divide the waters of the river.

Historic Background

Problems with water allocation and distribution along the Rio Grande between the United States and Mexico as well as Colorado, New Mexico and Texas extend back to the late 19th century. The United States and Mexico entered into a treaty in 1906 that allocated 60,000 acre-feet annually to Mexico. In 1905, Congress passed the Rio Grande Project Act which authorized the building and operation of the Rio Grande Project (hereinafter Project). The Project provided the storage and delivery system for Mexico’s treaty allotment as well as water allotments for the Elephant Butte Irrigation District (EBID) and the El Paso County Water Improvement District (hereinafter EP No. 1).

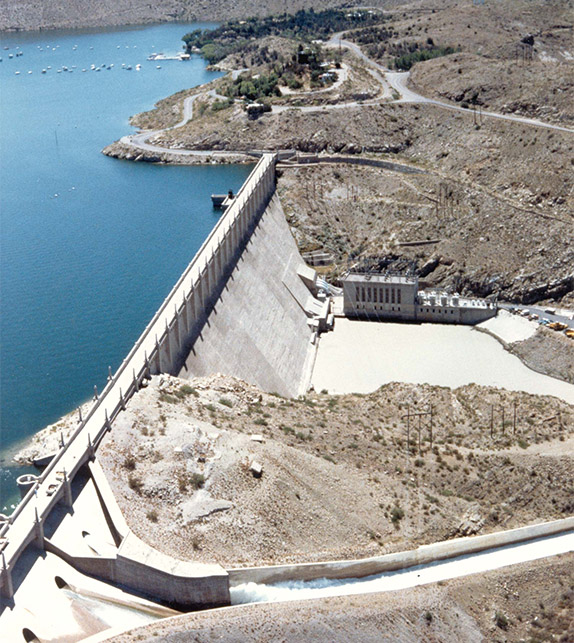

(Elephant Butte Dam and Reservoir)

(Elephant Butte Dam and Reservoir)

The Act provided that the districts’ allocations would be based upon a ratio of irrigated lands, determined by a survey conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (hereinafter Reclamation). The survey resulted in a ratio allotting 57% of the United States’ share of available annual Project water to EBID and 43% to EP No. 1. In 1938, the States of Colorado, Texas and New Mexico entered into the Rio Grande Compact to allocate water between the these sister States. Under the Compact, New Mexico is obligated to deliver water to Elephant Butte Reservoir for south-central New Mexico and Texas.

During the 1950’s drought, the Project surface water supply dwindled. Farmers on both sides of the state line turned to groundwater to keep their crops alive. In a Reclamation Annual report for 1954, the Bureau reported that storage “was so limited that even the first irrigation had to be made with a combination of water pumped from farm wells and water from the storage supply.” In 1956 – the worst year for surface allotments in the Project – Reclamation allocated .39 acre-feet or five inches per acre for the entire year. To cope with the surface water shortages, farmers on both sides of the state line drilled hundreds of supplemental irrigation wells. Reclamation Project Manager W.F. Resch issued “Water Announcements”, dated March 1, 1954 and June 21, 1954, requesting that farmers throughout the Project with irrigation wells use them “to the greatest extent possible… and to make available for transfer their allotment water to those farmers who do not have satisfactory wells.” The drought lingered until 1978 when relatively wet years prevailed. Drought conditions returned in 2003.

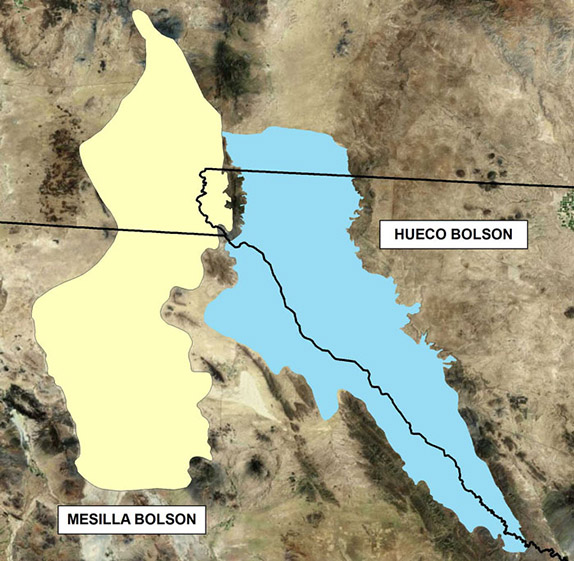

In and near the Rio Grande Project area, groundwater comes from the Rincon Bolson (aquifer) in New Mexico, the Mesilla Bolson shared by New Mexico and Texas, and the Hueco Bolson shared by New Mexico, Texas and Mexico. The number of groundwater wells grew during the drought years. In the 1954 “Operation and Maintenance of Irrigation System Report, Ysleta Branch” of the Project, Reclamation reported that 418 irrigation wells were constructed in the El Paso Valley of Texas between 1950 and 1954. In the mid-1950s between Anthony, New Mexico and south of the city of El Paso, two hundred and fifty irrigation wells were put into production.

More recently, EP No. 1 drilled sixty-two wells to supply farmers in EP No. 1 and the Hudspeth County Conservation & Reclamation District No. 1 located south of the Project. It is estimated that approximately 1000 irrigation wells were drilled in the New Mexico Mesilla and Rincon Basins during the 1950’s drought. During the 1970’s, EBID drilled several wells to supply supplemental water to the district.

In addition to irrigation wells, there are numerous municipal and industrial wells within and near the Project boundaries in both New Mexico and Texas. The city of Las Cruces and the city of El Paso have municipal well fields in the Mesilla Basin. The cities of El Paso and Juarez have large municipal well fields in the Hueco Bolson. In a 2012 press release, the New Mexico State Engineer reported that there are now about 3,000 metered wells in the Lower Rio Grande Water Master District.

From the late 1990s to 2008, the United States, EBID and EP No.1 struggled with how to manage the Project appropriately in light of groundwater pumping and surface water shortages. In 2006, Reclamation unilaterally implemented an operating procedure, the “ad hoc” procedure without the concurrence of the districts.

(Mesilla and Hueco Bolsons, Courtesy of El Paso Water Utility, Water Res. Dept.)

(Mesilla and Hueco Bolsons, Courtesy of El Paso Water Utility, Water Res. Dept.)

Both districts subsequently filed suit over the operations of the Project. In 2007, EBID filed suit in the New Mexico federal district court and, shortly thereafter, EP No.1 filed in the federal district court of western Texas. In each instances, the district sought resolution to the operations dilemma. The west Texas court immediately sent the districts and Reclamation to mediation and in 2008, they crafted the Operating Agreement Settlement for the Rio Grande Project (hereinafter Operating Agreement). The States of Texas and New Mexico were not parties to the negotiations.

The 2008 Operating Agreement changed the allocation method and operations of the Project. The parties to the agreement intended that it account for depletion effects on the river from groundwater pumping and increase management flexibility by allowing the districts to a limited amount of carry-over conserved water from one year to the next. The Operating Agreement changed the historic Project surface water allocations of 57% for EBID and 43% for EP No. 1 as well as the Project operations. According to the New Mexico Attorney General, the ratio for the allocation of Project surface water in 2011 changed to about 22% for EBID and 78% for EP No. 1. The Attorney General also asserted that under the agreement, EBID unfairly absorbs the depletions to the river from groundwater pumping on both sides of the state line. In exchange, EBID countered, it negotiated the 1951-1978 condition as the baseline for pumping effects rather than 1938 when the Compact was signed. According to EBID, this part of the agreement allowed the hundreds of groundwater wells developed between 1951 and 1978 to be “grandfathered” into the Project operations.” The carry-over provisions allowed EP No. 1 more flexibility for its surface water management.

In August of 2011, the New Mexico Attorney General sued Reclamation and the districts in the New Mexico federal district court, seeking to invalidate the Operating Agreement and to obtain an injunction against its use. New Mexico believes that Project operations under the agreement are grossly unfair to New Mexico farmers for several reasons. Under the agreement, EBID’s surface water allocation is reduced by more than 170,000 acre-feet in full supply years. New Mexico estimates that the value of the water and the taxes generated by water-related activities ranges from millions to billions of dollars. The reduction in Project surface water forces farmers to turn to groundwater to make up the difference. Reliance on groundwater threatens the sustainability of the aquifers underlying the Project. Farmers with no wells or with shallow wells are placed in jeopardy without surface water and so it is important, in New Mexico’s view, that the historic ratio of Project surface allocation remain in effect.

The New Mexico adjudication of all the water right claims to ground and surface water in the lower Rio Grande in the state court has been ongoing since 1997. This court will determine the United States’ claims in the Rio Grande Project in stream system issue 104. In its statement of claims, the United States claimed all the surface and tributary groundwater required by the Project.

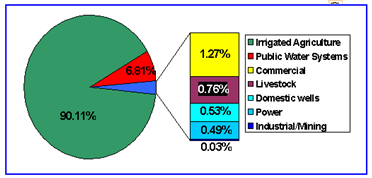

(Water Use by Sector in LRG, Courtesy of Dr. Phil King)

On August 16, 2012, the adjudication court entered an order resolving the first issue, “What is the source or sources of water for the United States’ Rio Grande Project right?” It held that the United States has established a surface water right under state law, but rejected the government’s claim for tributary groundwater. The court also found that the United States has adequate remedies under state law for any injury caused by groundwater pumping in New Mexico. The United States had claimed that groundwater supplying the river is a part of its rights because the Rio Grande Project system needs that water to make its deliveries to Texas and Mexico. The adjudication court ruled that this claim is unsupported by the Notices of Appropriation filed in 1906 and 1908. The court has set a briefing schedule for the determination of the United States Project right elements of priority and amount of water.

These rulings by the adjudication court echo rulings made in 1983 by the New Mexico federal district court. In that case, El Paso, et al. v. Reynolds, et al., the city of El Paso challenged the constitutionality of a New Mexico statute which prohibited the exportation of water from New Mexico. In determining that the statute was unconstitutional, the federal court ruled on the questions of whether the Compact “(1) apportions the surface water of the Rio Grande between New Mexico and Texas and (2) controls the use of groundwater hydrologically connected to the River.” As a part of its argument, New Mexico asserted that since the drafters of the 1938 Compact were silent on Texas’ share of the Rio Grande, they were relying on the Project managers to make the equitable apportionment of surface water between the two states through the contracts between Reclamation and the two Project districts. The federal district court rejected this argument finding that the Compact mentions neither the apportionment of water to Texas at the state line nor groundwater. The court also opined that if there are issues of impairment of senior rights resulting from groundwater pumping, those issues should be handled administratively. In today’s case, Texas brings that argument forward again, for review this time, by the U.S. Supreme Court.

South-central New Mexico is in water trouble. Finding solutions to the water requirements and entitlements of farmers and municipalities will be challenging. The law suits filed in the U.S. Supreme Court, New Mexico federal district court, and the State’s Third Judicial court are and will be expensive to pursue to their ends. As much as possible, these courts prefer parties to work out water problems outside of their doors but, if necessary, will shoulder the load of evidence, hearings and trials. If the Pecos version of Texas v. New Mexico is any indication, a loss in the lower Rio Grande lawsuit, Texas v. New Mexico, will pose a huge economic and social burden for the area for years to come.

For the full report, please visit the Utton Transboundary Resources Center.

May 28, 2013