☆ “Democracy” in Greek.

From the adoption of nascent democracy during Greece’s Golden Age, around 460 bce to this day, the system has been considerably altered.

In Athens, the center of trade and the arts, the citizens voted for their government officials. The Council and the Assembly ruled. The Council was made of 500 members who were drawn by lottery from the population. Stop for a second and visualize that today.

The two groups met every ten days and any citizen could speak and vote at the Assembly. However, they would only convene if there were at least 6,000 citizens present. Imagine that.

However, only adult male Athenians who had completed their military training voted and participated in politics—but this did not seem to denigrate the principles of democracy, even though slaves were a vital part of Athenian society. The ideal life to the Greeks was for a man to contemplate philosophy, while others labored for him. Although it has been amended since those times, for the better, both the ancients and we moderns began our democracies on the backs of human bondage.

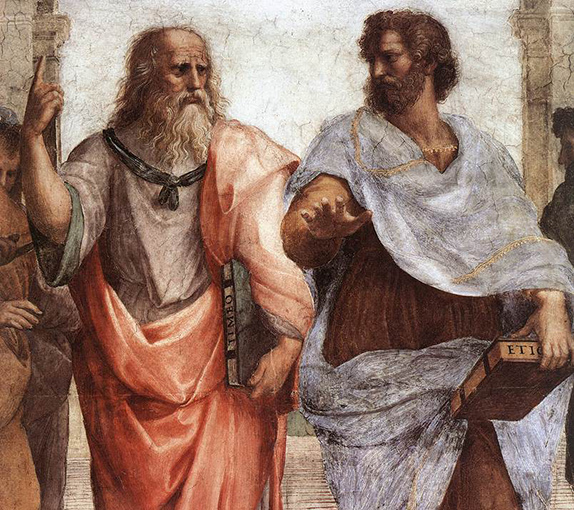

Aristotle, who was born in 384 bce, who became Plato’s pupil and Alexander’s tutor, believed that people reached their highest potential when they lived and worked in a city-state (polis)—a community small enough to be well governed. Aristotle also said, sounding more like Marx, “Democracy is when the indigent, and not the men of property, are the rulers.”

Seen through that lens, we have never had true democracy, as no indigent person has ever come close to governing; from the start of our democracy even landless white males were excluded from voting, as were African Americans, Native Americans, and women. John Adams wrote in 1776 that no good could come from enfranchising more Americans.

This changed when Andrew Jackson first opened the polls to Everyman in 1828. In his first Annual Message to Congress Jackson recommended eliminating the Electoral College, that residual roadblock to a simple majority vote. Of course Jackson himself represented the perfect paradox of a man who cared about the common folk, at the same time being a wealthy slaveholder.

In 350 bce Aristotle wrote the new Athenian Constitution. This is from his introduction, so you may see that class wars were evident during Aristotle’s time. It seems that inequality in society is ancient.

After this event there was contention for a long time between the

upper classes and the populace. Not only was the constitution at this

time oligarchical in every respect, but the poorer classes, men, women,

and children, were the serfs of the rich. They were known as Pelatae

and also as Hectemori, because they cultivated the lands of the rich

at the rent thus indicated. The whole country was in the hands of

a few persons, and if the tenants failed to pay their rent they were

liable to be hauled into slavery, and their children with them. All

loans secured upon the debtor's person, a custom which prevailed until

the time of Solon, who was the first to appear as the champion of

the people. But the hardest and bitterest part of the constitution

in the eyes of the masses was their state of serfdom. Not but what

they were also discontented with every other feature of their lot;

for, to speak generally, they had no part nor share in anything.

Following this doleful summation, Aristotle goes on to describe the changes in the new constitution. We get a sense of how they viewed democracy when Aristotle describes the court system and the voting process.

Most of the courts consist of 500 members…and when it is necessary

to bring public cases before a jury of 1,000 members, two courts combine

for the purpose, the most important cases of all are brought 1,500

jurors, or three courts. The ballot balls are made of brass with stems

running through the centre, half of them having the stem pierced and

the other half solid. When the speeches are concluded, the officials

assigned to the taking of the votes give each juror two ballot balls,

one pierced and one solid. This is done in full view of the rival

litigants, to secure that no one shall receive two pierced or two

solid balls.

After voting by dropping a ball into a brass urn, the citizen received a voucher for 3-obol (a silver coin). They paid voters to make sure they showed up at the polls. Think that would work today? You know it would.

John Nichols calls our system a “Dollarocracy” and he’s right; he’s talking super PACs, the Supreme Court, and corporate lobbyists. But paying people to vote, when almost half of the citizens who can vote, don’t, may be a good thing. Hey, if it was good enough for the Greeks. We also need to implement Andrew Jackson’s idea of getting rid of the Electoral College. Isn’t it about time? Do you really think Aristotle and his fellow Athenians would stand for such a thing?

So, from the start the whole notion of democracy was flawed, and still is, but its promise was great and the ideals it pronounced were like an elixir to those who had existed in an autocracy, as had our so-called Founding Fathers. Today however we exist in another oligarchy, which Aristotle resisted at the start, yet almost 2,500 years later we are fighting that fight all over again. I wonder who will write the new constitution of this nation? Someone who at this moment is indigent and homeless? Now that would mean democracy had reached its apex of achievement in all history.

Aristotle would love that.

August 05, 2014