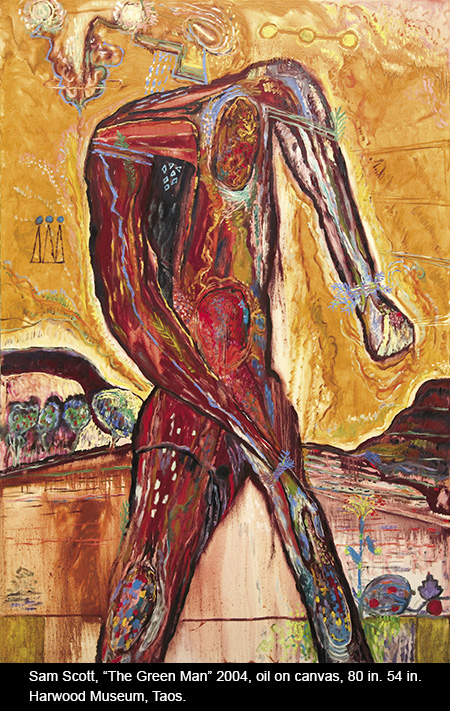

Sometime in 2004, concerned about global warming and the looming ecological crisis, and still disturbed by the aftermath of 9/11 and the obtuse flailing response of our political leaders to both crises, Sam Scott was surprised to discover a lone humanoid figure appearing again and again in his sketchbooks. Somehow his hand just kept drawing the thing. Marked with gaping wounds, it was a heroic human form, but it appeared to be composed of the stuff of the earth itself—of rocks and plants and weather. He realized he would just have to paint these mysterious embattled beings and try to discover what they had to tell him.

The paintings that resulted were recently put on display at the Center for Contemporary Arts (CCA) in Santa Fe (through November 2 at 1050 Old Pecos Trail).

On their first appearance, Scott began calling them “Messengers.” “They are healers, guardians, elders,” he said. “They come to us trailing tenderness and compassion, but they are wounded and even a little fierce.”

“Messengers,” of course, is just another word for “angels.” But Scott’s figures seem to have risen out of the earth of their habitation. And although it is clear that they are spiritual beings meant to mediate between heaven and earth, they are undeniably earthbound. Summoned by awareness that human disregard has produced the planet’s environmental distress, their mission is to promote reconciliation between the human and the natural world. In that sense, Scott’s “Messengers” are more like the messenger-god Mercury of “New Mexico Mercury”—a bringer of “intelligence” from a watchful and wounded conscience that wants to promote understanding in order to help set things right within the human community.

Scott has now taken to calling his figures “The Wounded Healers.”

Writing about Scott’s figures in Orion magazine (July/August 2008), anthropologist Peter Nabokov called them “Earth protectors,” and went on to describe them as “huge entities that seemed like walking landscapes in their own right, their bodies composites of the very mesas, rainclouds, sunbursts, sheer cliffs, green growths, lightning strikes, tree stumps, rivers, and canyons for which it was their charge to suffer, but also to safeguard.”

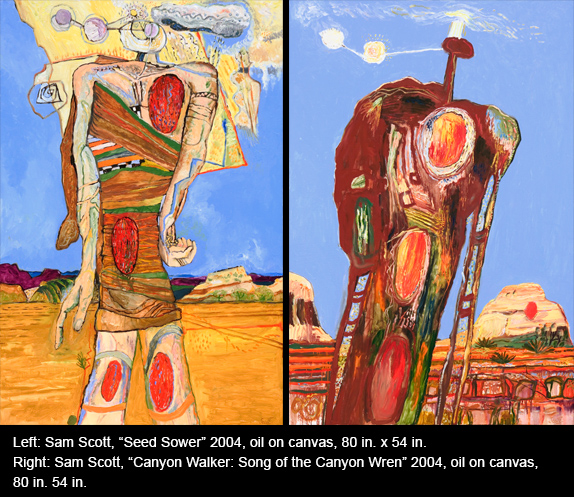

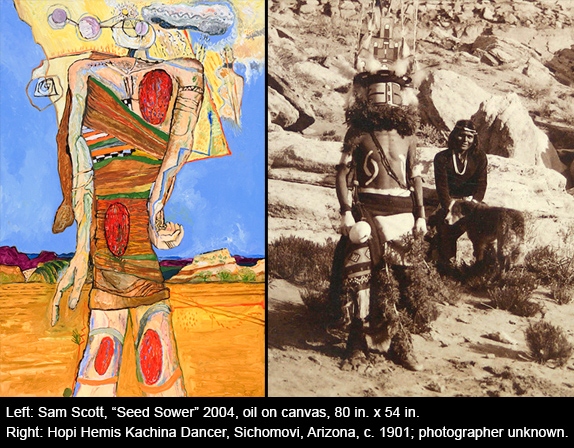

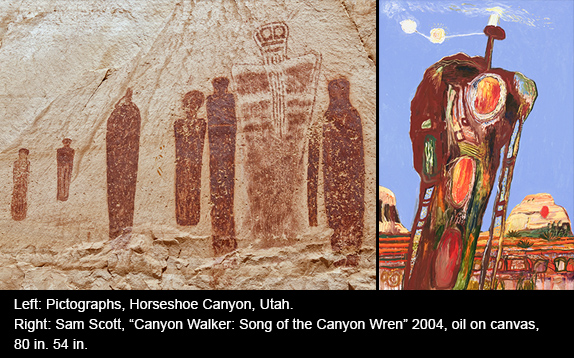

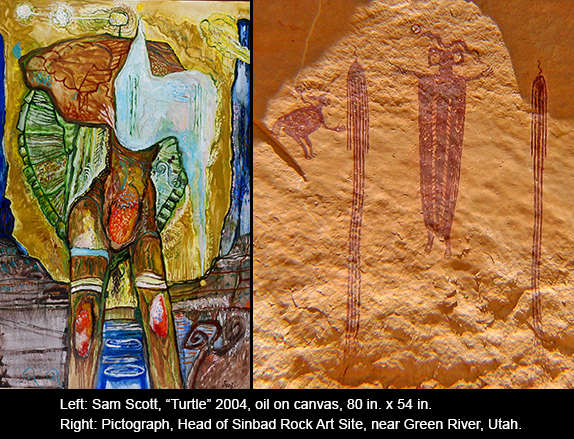

A scholar of Native American traditions and spirituality, Nabokov recognized the kinship between Scott’s figures and the “spirit intermediaries of the Pueblo Indian cosmos, otherwise known as masked kachinas.” And he saw how their forthright, broad-shouldered forms echo the “ghostly pictographs of sentinel-like vertical figures…the color of dried blood” painted by ancient indigenous people on the walls of Utah’s Horseshoe Canyon.

Looking at Seed Sower (2004), the first of these guardian figures to be painted at a monumental scale of 80 by 54 inches, it’s not hard to see the influence of Pueblo dances and their invocation of agricultural fertility. And Canyon Walker: Song of the Canyon Wren (2004) could very well have climbed down from among the pictographs on Utah’s canyon wall, its scaling ladder transformed into crutches to convey its damaged body across the desert landscape.

From the time of his arrival in Santa Fe in 1969, Scott has dawn inspiration from the region’s ancient inhabitants and its enduring Puebloan cultures. Responding as well to the varied landscape, he developed a richly colored, expressionistic mode of abstraction with forms based in his experience of the high desert environment. His approach often admitted a kind of fugitive figuration that would hint at recognizable forms, but would more often submerge them within the dynamics of an otherwise abstract format. For followers of Sam Scott’s art, one of the most startling aspects of these figure paintings is their literalness.

In “Hopi Kachinas: A Life Force” Barton Wright tells us that “The central theme of the kachina cult is the presence of life in all objects that fill the universe. Everything has an essence or a life force, and humans must interact with these or fail to survive.” It is this ecological consciousness of the interconnectedness of all things that Scott hopes to invoke with his series of singular guardians.

“Kachinas are the life forces of the cosmos that surround the Hopi,” Wright continues. “Each of these forces, regardless of their physical appearance in the normal world, is a pseudo-morphic human in the supernatural world. These beings possess attributes that humans do not have, for kachinas can make it rain, cause the crops to grow well, or bring a multitude of other benefits if they are properly treated.”

Behind Scott’s earth-walking figures is a similar impulse to give these unseen forces a coherent form, to personify them and make them accessible. As Wright notes, “It is much easier to interact with impersonal forces if they are given life forms and if patterns of reciprocity and mutual obligations are established. It is these visualizations, these personifications, that are the kachinas.”

Wright explains that the Hopi cosmos is divided between the tangible world and the spiritual realm: “Where one half is composed of objects and beings of solidity and mass, the other is an ethereal, imponderable world of cloud-like beings.” According to the Hopi, “Evidence for this [spirit] world lies in the clouds that rise above mountain peaks, the smoke from burning objects, the fog that arises from water on a cold morning, steam from hot food, the breath of living beings that leaves them when they die and passes into the other world.”

A dazzling, churning atmosphere surrounds each of Scott’s Healers—apocalyptic clouds and thunderheads, planetary alignments and starry events, or a shimmering solar warmth—all of which suggests a similar concept to the Hopi’s, though charged with crisis as well as blessing. Significantly, Scott’s figures have no masks; indeed they scarcely have heads at all. In place of thought, they elevate feeling. “In place of heads,” Scott said, “they have these tiny little glyphs that may have associations with a milkweed pod or a dandelion. The parachutes that drift away from them are…as fragile as prayers, and they might be prayers, moving into the cosmos.”

In that regard, Scott’s Healers take up the theme of the “Peace Prayer,” which has been a recurring element of Scott’s art from the late 1960s and the period of the Vietnam War. The message of the Healers is essentially that of the famous Peace Prayer once attributed to St. Francis: “Lord make me an instrument of your peace; where there is hatred, let me sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light. Grant that I may not so much seek to be consoled as to console; to be understood as to understand; to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we receive; and it is in pardoning that we are pardoned.”

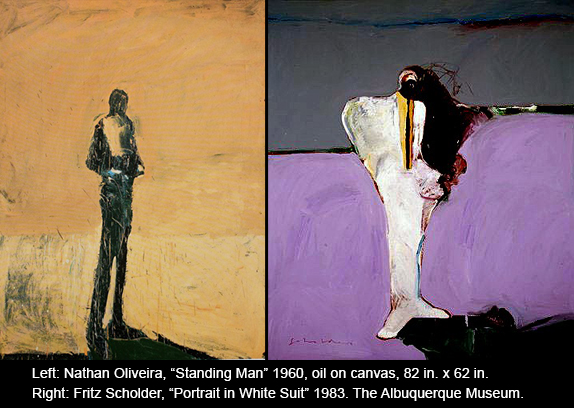

Of course there are many precedents for Scott’s burly “Earth protectors,” both in his own art and in the history of image making. They immediately call to mind the lonely, defiant standing figures painted by Nathan Oliveira and Fritz Scholder, which in turn draw on the early example of Giacometti.

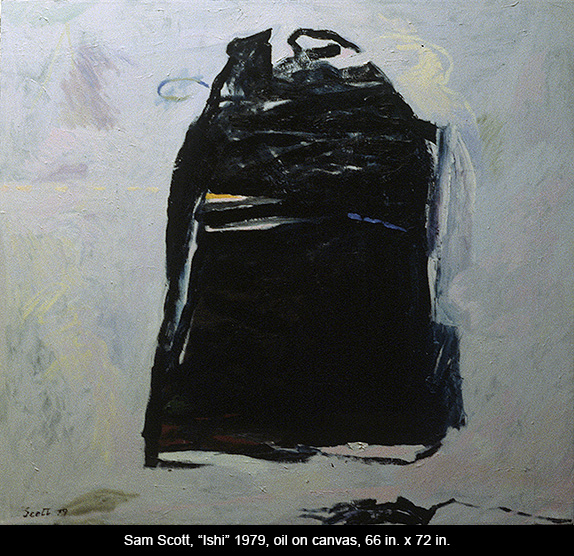

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Scott had taken up a similar theme of the “Dark Hero” in a series of works that dealt with their subject matter in an abstract manner. Scott’s Ishi (1979), for example, pays homage to the heroic California Indian—the only surviving member of his tribe and the last speaker of his native language—and yet Ishi is not literally rendered. Instead, Scott utilized slashing brushstrokes to shape a dark, isolated and ambiguous form that appears to have been ravaged by time and opposition, but still smolders inside with inextinguishable emotion and the refinement of an inner light. The same is true of The Heart of Pablo Casals (1980), a throbbing mass of brushwork that erupts and sputters with defiant feeling and represents the soul and sound of the famed musician, but not his physical appearance.

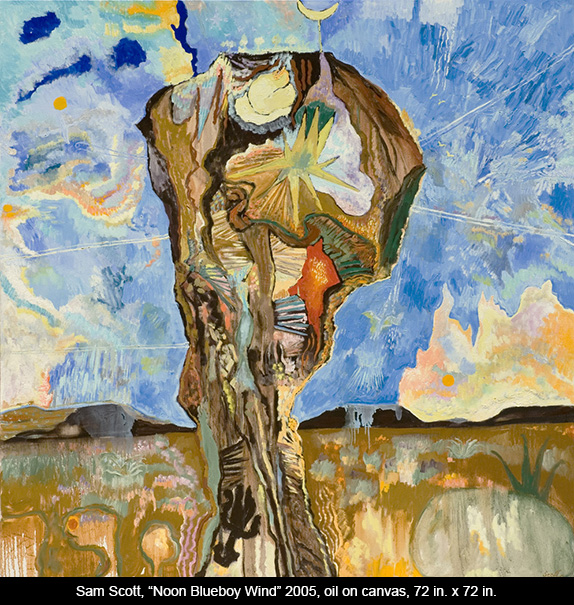

For my own part, I prefer the ambiguity and broader reference of Scott’s abstract “Dark Heroes.” But, as they evolved, the Wounded Healers began to take on a greater complexity of internal form and eventually reverted to the kind of charged monolithic mass of the earlier abstract works. The difference, however, is that they are composed of bits of representative natural elements that are so richly painted they might almost have been torn from a landscape by Van Gogh. This is especially true of Corn (2005) in which the right contour of the shoulder, arm, thigh and leg of the figure is undergoing a metamorphosis into tree bark while the entire interior of the hollow trunk is disintegrating and renewing itself into a series of topsy-turvy landscape ribbons, plant forms, leaves, and a waterfall. There’s a joyful resurgence within decay here that is like shouting to make echoes while standing deep inside a desert canyon brimming with summer sunshine. The effects are exhilarating.

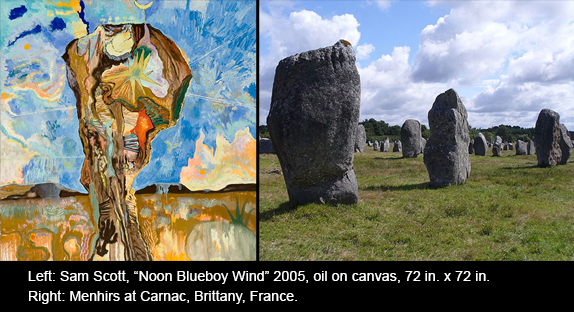

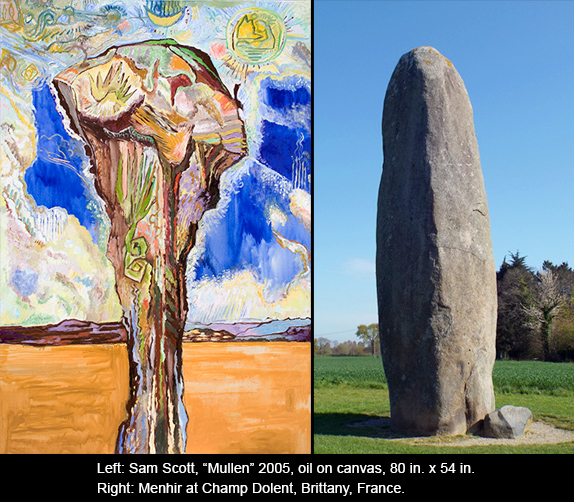

Noon Blueboy Wind (2005) is perhaps the masterpiece of the group for its solid realization and its noble evocation of the eternal renewal of nature within its cycle of decay and rebirth. Its anthropomorphic form is that of a blasted tree trunk, which surges inside with restorative forces culminating in a starburst. Mullen (2005), which improvises on the theme of the familiar gray, fuzzy-leafed plant with its dry, sentinel-like seed stalk, is a near rival in its expression of tough endurance. But the monolithic forms in both paintings are like the great menhirs of prehistoric Brittany—those painstakingly erected standing stones, each weighing several tons and seemingly meant to become a stand-in for a humanly conceived spirit, perhaps an ancestor or some individual member of the human community. Each stone, as a solid piece of the earth, drawn and emplaced upon the earth, was meant to be as enduring and permanent as the earth itself, and yet to stand out from it—like a defiant human being standing its ground in the open landscape. It is an ancient human impulse, the desire to provide human transience with the reassurance of an enduring presence.

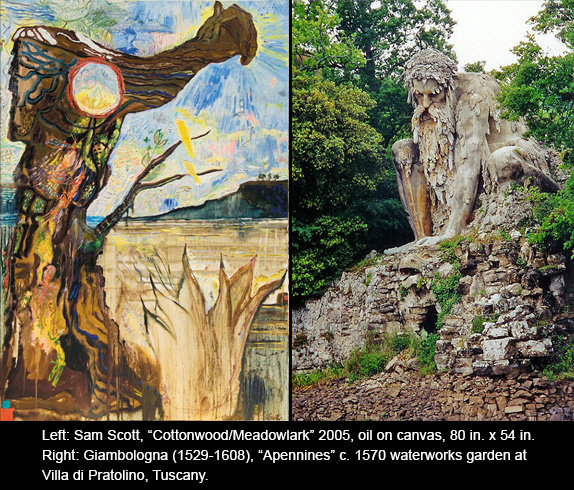

A more whimsical version of the tree trunk motif occurs in Cottonwood/Meadowlark (2005). It reminds me of Giambologna’s craggy earth god in the waterworks garden of the Villa di Pratolino in Tuscany (c. 1570). Nature personified, it is an anthropomorphic representation of the Apennine Mountains and their winter snows. The human search for harmony with nature can take many forms, and there is sometimes a childlike sweetness in Scott’s discoveries that can be as therapeutic as his more thundering efforts.

It was C. G. Jung, the great psychologist (1875 – 1961), who first coined the term “wounded healers.” Jung saw that empathy and compassion are central to any physician’s cure, and he felt that psychiatric analysts are often compelled to treat the emotional pain of others because of their own personal psychic wounds. “A good half of every treatment that probes at all deeply,” Jung wrote, “consists in the doctor’s examining of himself…. It is his own hurt that gives measure of his power to heal.”

Because of his interest in universal archetypes, Jung invoked the Greek myth of Chiron the Centaur as an exemplary wounded healer. The misbegotten Chiron, half horse and half man, belonged to a race of wild creatures who were drunken and disorderly and deemed the very opposite of civilization. But Chiron was himself wise and had been gifted by the gods with immortality. As he was skilled in archery, he was charged with the training of such heroes as Jason and Achilles. Accidentally wounded by one of Hercules’ arrows, which had been poisoned by the blood of the Hydra, Chiron lived in agony, unable to die. Despite his pain, he continued to do good works of healing. (“Chiros,” the root of his name, means “hand” and the Greek word for “surgeon” was “chirourgos;” the sense of a “skilled or healing hand” is still present in our word “chiropractor.”) Eventually, out of compassion for the bound Prometheus, Chiron secured his release by agreeing to take his place in Tartarus. By means of this self-sacrifice, Chiron could die and be released from his own suffering. The gods took pity, however, and transformed Chiron into the constellation of Sagittarius.

One of Chiron’s pupils was the demigod Asclepius, son of Apollo, who was worshipped in ancient Greece as a healing figure. As a psychiatrist, Jung appreciated the tradition that suppliants in search of healing went to the temple of Asclepius at Epidaurus and actually slept inside, where they had their cure conveyed to them in their dreams. Asclepius’s symbol was that of a snake wrapped around his staff. The snake may have been a reference to Asclepius’s father Apollo, who brought enlightenment and health to the world when he slew the chthonic Python at Delphi. Or it may have been that serpents were long associated with the dual nature of medicinal drugs and surgeries, a danger to life as much as a risky benefit. Because it could renew itself by shedding its skin, however, the snake seemed an apt image of how one regained health by sloughing off illness.

Sam Scott was aware of these ancient predecessors for his Wounded Healers, and felt their presence when his lonely striding figures emerged. One of the earliest of his figures was drawn directly from the Homeric tradition and titled Planting of the Oar (2004). This image of a bruised and bloodied and aging hero had its source in The Odyssey, Book XXII, when the returning Ulysses tells his wife Penelope that his trials will not be over until he has fulfilled a prophesy of Teiresias, foretold in the Underworld. “Teiresias told me to travel through many cities of men, carrying my shapely oar, until I came to a place where no one had ever heard of the sea…. There I must plant my oar in the ground and make a sacrifice to the Lord Poseidon.” Only after this task was performed would Ulysses see peace and prosperity restored to his land of Ithaca.

What appealed to Scott was the idea of a final healing ceremony, performed by the wounded hero as a culmination of his quest and as a token of the end of homeless voyaging and the restoration of peace in the land. A ritual burial of the past, its restless striving and its cumulative damage, is somehow necessary for achieving peace of mind (closure) and the peace of the community. In this regard, he placed in the center of the installation at CCA a great heap of source material for his “Wounded Healers”—a kind of shrine of gathered personal mementoes like those left by mourners at the newly opened “Ground Zero” memorial to 9/11 in New York.

But there is another tradition of Wounded Healers that Scott draws upon, one even older than Homer and the Greeks: the ancient tribal role of the shaman.

Scott has had a long familiarity with tribal shamanism. As a teenage seminarian, he spent time on the Cheyenne River Reservation and studied tribal religious concepts with the Oglala Sioux. And in 1968, as an ethnographic artist assigned to a scientific research team living among the Makiritari in the Brazilian Amazon, he was able to observe the practices of the tribal shaman Don Pedro, who could summon the voices of the jungle with his flute.

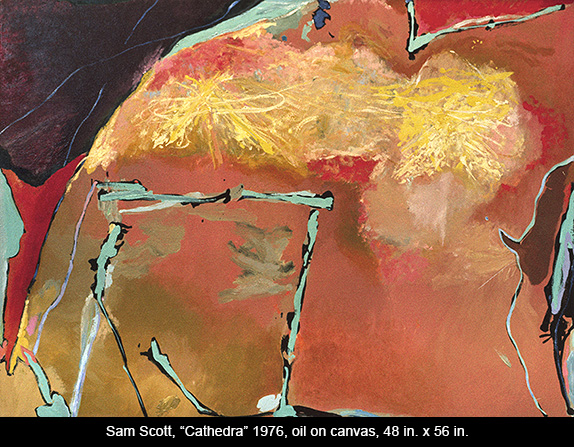

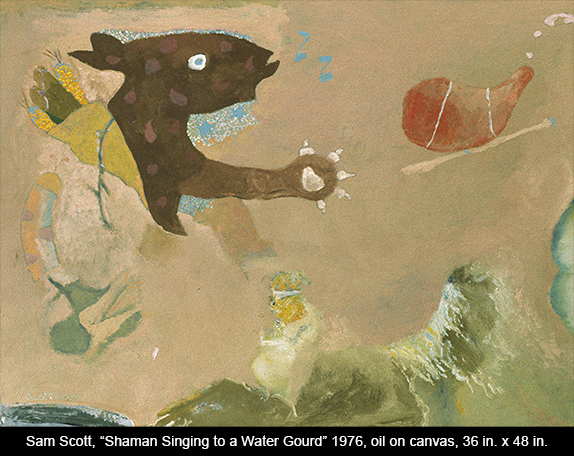

I remember that there was a shamanic component in the very first exhibition I ever saw of Sam Scott’s work. At the time I was writing an Art column for the weekly New Mexico Independent (where V.B. Price had a City column). In the July 9, 1976 edition I wrote: “Sam Scott’s recent works are the testament of a major mythopoeic sensibility. The paintings are resonant with elements of shamanism, Symbolist poetic correspondences, and an animistic brushwork, which in its spontaneity evokes the intimate intermingling of creation and destruction in the formative processes of nature.” (Clearly, there are aspects of Sam’s themes and my own logorrhea that remain persistent.) That show included both abstract works, like Cathedra (1976), and the figurative Shaman Singing to a Water Gourd (1976).

Anthropologists identify shamans as individuals in tribal societies who have become an intermediary between the human community and a presumed spirit world. Shamanism may be the world’s oldest religion. However, as Weston La Barre has noted, “Unlike priests, who preside over a codified religion with beliefs and rituals that have become routinized on the basis of some received supernatural revelation, shamans derive from a direct, individual, visionary experience of the supernatural, in dream, in trance, hallucination, or some other dissociated psychic state.”

In times of crisis, the shaman is called upon to make contact with the spirit world, and through visionary experience seeks to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the human community. These may be crises of illness or disease for which a cure is sought, or they may be more widespread occasions when life itself seems out of balance—famine, warfare, social unrest, scarcity of game, adversity of weather, drought and endangered crops.

Nevertheless, in tribal societies the shaman is usually someone set apart, a kind of outsider living on the fringe, one who is given to uncommon behavior and is sometimes not unlike a mentally disturbed homeless person in our society, hearing voices, arguing with invisible interlocutors, befriending feral animals. An element of suffering and psychic pain has shaped the shaman’s character. “Often of unstable or abnormal type,” wrote La Barre (in The Ghost Dance, 1971), “often transvestite, sometimes even psychotic in our society’s terms though not necessarily in their own, the shaman may be seen as the individual most threatened by the uncertainties of life, and perhaps also the most unable to meet them on practical secular…terms. But at the same time it was the shaman whose autistic defenses against these threats and anxieties obtained ‘solutions’ of which the society stood in dire need.”

While the shaman’s activities are undertaken on behalf of a confused and anxious community in crisis, according to Claude Levi-Strauss (The Savage Mind, 1966), the function of the shaman is “to reproduce and restore belief, not just physical health.”

In that regard, as a visionary outsider in quest of imaginative solutions to psychic distress, uncertainty, and other problems confronting humanity, the shaman’s role closely resembles that of the artist. It is basically the role Sam Scott has given his Wounded Healers.

For Jung’s Wounded Healer the important thing was to recognize that the wound of psychic pain resides in each of us: it is as universal as our navel scar. It is part of the shared psychic make up that Jung identified as the “collective unconscious.” The wound lies at the heart of our sense of dissociation and the terrible split with nature that has contributed to our present environmental crisis. There is a direct correlation between the violence we observe in the human community outside us and the wound we feel inside, because its source is a split within the self. For Jung, recognition that the wound is an inevitable aspect of incarnation is the source of the Wounded Healer’s compassion.

In a final note on the shaman, La Barre (Flesh of the Gods, 1972) uses terms echoing Jung, “We have too long supposed that the Unknown mysterium tremendum et fascinosum of religion was outside us, when in fact that Unknown, although ego-alien or unconscious, was all the while within us: the alleged ‘supernatural’ is the human subconscious.”

In trying to come to terms with the high moral concern of Scott’s Wounded Healers, I am reminded of another incident of faith and suffering and interaction with Native Americans. Writing in Santa Fe in the 1930s, Haniel Long composed an Interlinear to the narrative account that Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca sent to his king describing his perilous journey in the “unknown interior” between 1528 and 1536. Shipwrecked after an abortive attempt at the conquest of Florida, Nuñez was left to make his way to Mexico, eventually joined by three other survivors. For eight years the Spaniards wandered, facing horrific privations among both hostile and friendly natives and becoming the first Europeans to cross the Southwest as far as the Gulf of California. In his 1936 Interlinear, Long gives poetic voice to Nuñez’s discovery that he and his three companion survivors had acquired the capacity of faith healers in the eyes of the Indians they encountered. The ability to heal astonished them and remained a complete mystery: “That power we had felt flowing in us and through us could not, in the nature of things, be accurately conscious of us as individuals. It must come rather as wind comes to the trees of a forest, or as the ocean continues to murmur in the seashell it has thrown ashore.”

Nuñez is very much moved by his experience and by the Indians’ willingness to believe in his capacity to heal. His suffering brings him to a depth of compassion that also lies at the heart of Sam Scott’s Wounded Healers. “And who is any of us,” Long’s Nuñez cries, “that without starvation he can go through the kingdoms of starvation?” The message to be taken from these paintings is paralleled in Long’s reading between the lines, and it is worth quoting at length. At the end of his narrative to the king, Nuñez describes his feelings about re-entering a European way of life:

It was many days before I could endure the touch of clothing, many a night before I could sleep in a bed…. At first I did not notice other ways in which our ancient civilization was affecting me. Yet soon I observed a certain reluctance in me to do good to others. I would say to myself, Need I exert what is left of me, I who have undergone tortures in an open boat and every privation and humiliation among the Indians, when there are strong healthy men about me, fresh from Holy Church and from school, who know their Christian duty? – We Europeans all talk this way to ourselves. It has become second nature to us. Each nobleman and alcalde and villager is an avenue that leads us to this way of talking; we can admit it privately, your Majesty, can we not? If a man need a cloak, we do not give it to him if we have our wits about us; nor are we to be caught stretching out our finger in aid of a miserable woman. Someone else will do it, we say. Our communal life dries up our milk: we are barren as the fields of Castile. We regard our native land as a power which acts of itself, and relieves us each of exertion. – While with them I thought only about doing the Indians good. But back among my fellow countrymen, I had to be on my guard not to do them positive harm. If one lives where all suffer and starve, one acts on one’s own impulse to help. But where plenty abounds, we surrender our generosity, believing that our country replaces us each and several. – This is not so, and indeed a delusion. On the contrary the power of maintaining life in others lives within each of us, and from each of us does it recede when unused. It is a concentrated power. If you are not acquainted with it, your Majesty can have no inkling of what it is like, what it portends, or the ways in which it slips from one. – In the name of God, your Majesty,

FAREWELL

A book surveying Sam Scott's fifty-year painting career is currently in development at Fresco Books in Albuquerque. To support this project and help defray the costs, there are two special patron editions available: A Deluxe Edition at $2500 which includes an original oil painting; and a Collector's Edition at $1300 which includes an original watercolor painting. To view the available paintings and for more information go to www.frescobooks.com and click on the Sam Scott link.

October 30, 2014