Sometimes it’s only after the right book has come along that you know it’s something you’ve needed to read. It sets you thinking about your world in a different way, one you knew was there but couldn’t find.

Such books seem to almost magically appear. My friend the poet and teacher Levi Romero recommended that I read a book called “Resolana”. After several promptings, I finally have.

And it turns out, indeed, to be the book I’ve needed. It’s started me thinking hopefully again about grassroots activism, about the possibility of local people thinking together in intelligent ways and changing the course of the difficult conditions and problems they have to face.

And that’s what great books can do for you, start you thinking in a different direction.

The Age of Babble had distracted me, with its top down problem solving, its edicts disguised in the bafflements of endless marketing, the pestering of commercial and political propaganda, and the roaring white noise of sound bites and poison snippets.

We are expected to agree not only with pronouncements from above, but with the moral polarities they offer up as truth, even if they make no sense at all. If we don’t submit, we are often set up by ideological bamboozlements to slump into inert confusion.

But Resolana presents a very different picture. Written with metaphoric eloquence, it’s full of rich examples and mind opening interviews. It explains an alternative tradition to top down thinking evolved over centuries in Northern New Mexico. It was called "resolana" and was based on grassroots dialogue that stressed the power of respectful listening, exchange of information and a belief that people coming together could figure out their own lives.

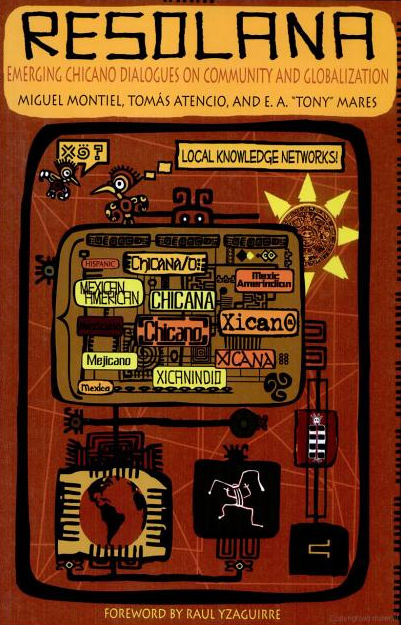

Resolana: Emerging Chicano Dialogues on Community and Globalization was published by the University of Arizona Press in 2009. Its authors are Miguel Montiel, emeritus professor at Arizona State University, and Tomas Atencio and E. A. “Tony” Mares, both emeritus professors at the University of New Mexico. They’ve created a brilliant, useful, and hopeful book.

By exploring a highly localized method of community problems solving, the authors give us an example with which to reinvigorate the long buried notion of grassroots wisdom and self-help.

Resolana stresses the local over the global, the civil over the commercial, the patient over the frantic, and consensus over persuasion.

For example, it helps me see that while the problems of drought may be “universal” in the southwestern United States, there are no universal solutions because there are no universal conditions, only local ones derived from local landscape, history and custom.

To understand water issues in the West, for instance, it is imperative that we understand local differences rooted in local realities. When New Mexico deals with Colorado over water, it’s essential to understand that unlike New Mexico whose senior water rights are held largely by agrarian communities, not cities, in Colorado where mining, not agriculture, was the major economic force, cities hold senior rights. The water problems both states face, as members of the Colorado Compact, are indelibly rooted in their histories. Grassroots realities dominate. But if local people aren’t thinking clearly about water and making wise decisions, top down problem solving from the federal government will, in effect, try to wipe out their history and the local facts that lives depend on.

As I read in Resolana, I was reminded that the globalized world of information technology hides, if not smothers, the reality of local life all over the world. The local is troublesome. It gets in the way of great global marketing schemes. Local reality is subjugated, denied, or erased.

The concept of resolana as described in the book’s introduction is derived from “resol (the reflection of the sun) and refers to the sunny side of a building where villagers gather to talk while protected from the elements. It is our metaphor for awareness.”

From dialogue emerges el oro del barrio, the “collective wisdom” of the village. “These ideas make possible the development of a ‘learning society,’ in which learning and knowledge building in everyday life can develop the policy priorities for a postindustrial society.”

What a profound difference it would make to live in a learning society rather than the public relations society which entraps us all.

As Mares writes, “Resolana offers hope for the future, a better future, even though at times it may be a messy future. On a local and on a larger geopolitical scale, we need to meet, talk endlessly, and reach intelligent, proactive compromises.”

“I think every culture has its “resolana,” Atencio writes, “…where people gather to visit and that they use as a place for dialogue and reflection.”

Epicurus had his garden, Socrates his agora, Zeno his stoa. Where are the places of dialogue and reflection, the resolanas, in modern Western society? They are potentially in neighborhoods, in the workplace, in citizen action groups, in farming cooperatives, in the blogosphere and other cyberspace networking possible on the internet.

Grassroots wisdom has a tendency to revolt against disempowerment. But the modern world doesn’t have much room for resolana yet. But when the top fails, and the global goes sour, or even mad as it seems to be doing now, the bottom, the local, has no choice but to take itself seriously and work to make a difference.

Atencio describes resolana as a “process of disclosing experience and its meaning through dialogue and reflection, bring to light in a place of light what is covered up.”

What’s important in such a dialogue, if it is to become a “beacon for productive living,” is, as Montiel writes, that no group’s knowledge be “subjugated” and dismissed.

In his final chapter on resolana and networks, Mares writes that “we live in a permanently linked world. It would take an unimaginable reversal of science, technology, and the human desire to communicate with others to undo our present networked world. “

While networks “could be used in support of nefarious ideologies to control countless human lives across cultures,” in contrast they could also “offer a support system, the communications infrastructure, for a constructive approach to globalism that respects and celebrates cultures.”

Montiel, Atencio, and Mares inspire us to think again about the role of cooperative and respectful listening and truth telling in the lives of healthy societies, localities, cultures, and people.

As a New Mexican, reading of resolana reminds me that it is possible to conceive once again of oases of fruitful dialogue, small learning societies that can, through articulate wisdom, be beacons of practicality, compassion and common sense for their communities.

Resolana makes it clear that it is possible to rise above zero sum partisanship created by external forces that see localities as zones of lucrative exploitation, caring nothing for the people who inhabit them.

The image of the sunny wall where people can talk and think together is a sustaining one. I’d like to think the Mercury is starting to build such a place. I hope it proves true. It is our intention to be of use.

May 20, 2013