Adolph Plummer, Roger Bannister, and Bob Beamon

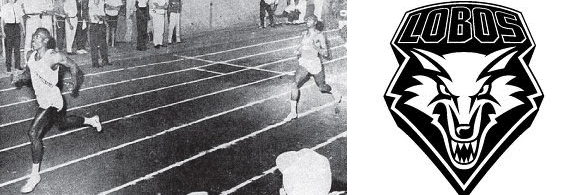

This year is the 50th anniversary of the greatest athletic accomplishment of any New Mexican. It was on the night of May 25, l963, in Tempe, Arizona that University of New Mexico quarter miler Adolph Plummer shattered the world record in the 440 yard dash by eight tenths of a second and crossed a psychological and physical line no one had really contemplated before. He ran 44.9, one tenth of a second under the 45 second barrier.

Plummer’s track nemesis Ulis Williams of Arizona State, consistently the best quarter miler in the nation, was five or six yards behind, and yet even he broke the existing world record.

To many of us in New Mexico this was a feat comparable to Roger Bannister’s breaking of the four minute mile (in 3:59.4) in1952, eleven years before. And it ranks right up there with long jumper Bob Beamon’s fantastic leap of 29.2 feet in the l968 Olympics in Mexico City, blasting the world record by 21 plus inches.

Yet if one looks up the names of Plummer, Bannister and Beamon on the web one finds a disappointing discrepancy. Bannister and Beamon get considerable write ups on Wikipedia, for instance, but Plummer gets a mere paragraph. And although Plummer is well represented in various UNM and Albuquerque Hall’s of Fame, the event of the 50th anniversary of barrier-breaking achievement has not been ballyhooed as it should have.

But there is an excellent and detailed account of that night in Tempe. It was written by Pete Brown on the blog OnceUponaTimeInTheVest --that’s right, vest – a site devoted to track doings from the l950s and l960s. Brown, a fine 880 runner on the UNM’s track team of those years, concludes his reminiscence by saying:

Fifty years have passed and many of us wonder what kind of time Adolph would have been able to achieve given a rigorous training regimen, use of resistance training for added strength, state-of-the art nutrition, modern shoes and, most important, today’s synthetic running surfaces. From this writer’s point of view, he would have been able to compete with anyone who has ever run the event, world record holder Michael Johnson included.

I had the great joy of knowing Adolph well before he broke the record. I was a fourth rate walk-on on UNM’s track team, and he was, even then, a major star. I’ve never met a nicer or kinder guy. He went on to become a distinguished educator in the Denver public schools, and served for a time as an associate dean in the Athletic Department at UNM in charge of education. He now resides in Colorado.

Plummer gave us one of the great sporting thrills of our lives. And it was all long ago when track had a certain purity to it, when runners were amateurs, and competition had not yet been corrupted by money.

Quarai and Mountainair

Driving through the forested Manzano Land Grant on New Mexico 333, the old South 14 behind the Manzano Mountains, one crests a wooded hill, and sees in the far distance the whole Estancia Valley spread out in lines of muted blue and the sandy greens in what used to be the greatest pinto bean farming land in the state. It’s one of those breathtaking New Mexico moments. It’s the same with the red sandstone ruins of the 17th century mission church of Quarai down the road.

The shock of coming upon Quarai’s towering walls, that seem to burst from the landscape as you round a corner amid the pinions and scrub oak, can almost change your life, no matter how many times you’ve seen it.

You realize that the surprise of beauty is potentially everywhere. It takes you out of whatever flat line depression that may be dragging you down. The majesty of Quarai’s stone architecture, the suffering and struggle it represents, changes your frame of mind completely.

Known formally as El Mision Nuestra Senora de la Purisima Concepcion de Cuarac, the mission at Quarai was designed, apparently, by Franciscan Frey Juan Gutierrez de la Chica, and completed in 1627 virtually on top of an existing Pueblo of Tiwa and Tampiro speakers.

Because of famine and constant Apache raids, the mission and the pueblo were abandoned 45 years later in 1674, never to be re-inhabited. It even came to house the Holy Offices of the Inquisition. The present site is a National Historic Landmark and has been designed not only as a historic ruin to be explored, but also as a serene walking environment among cottonwood and willow groves and remnant berry gardens for which Quarai was famous long ago.

Big owls reside in the mission ruins now, high in the notches built to hold the roof beams. I experienced them once flying through church drenched in moonlight. On a recent visit the owls were in evidence again, this time by remains of their scat near one of the walls with hundreds of tiny white mouse bones littering the ground like a paleontological puzzle in miniature.

Why is it that the leavings of time can move us so deeply and transport us so far? Do they become shrines to the permanence of change? Is it that they defy history, being themselves ruins of the past which can never return and yet are present and perfect in their current state of being? Quarai itself is beautiful without explanation even if one can surmise its history of religious wars and conquest.

A dramatic peacefulness has settled over the site since it was restored and shored up in the l930s. It’s the peacefulness of battlefields and pyramids. Being here is very much like having discovered for yourself an ancient text in a library you’ve happened on by accident, a text which reveals to you a new depth to your own humanity and a fuller understanding of the creative force of nature powering the imagination of humankind.

Herb Smith and the City Election of 1974

I’ve often thought that Albuquerque would be a very different place had Herb Smith not lost to Harry Kinney in the first mayoral race of the modern era.

The election was a match between two passionate constituencies – those who saw physical growth and population expansion as the essence of economic progress and those who saw historic preservation, environmental conservation, cultural nurturance and the prudent use of resources and public capital for the common good as the essence of a humane politics. The former won by slightly more than 2000 votes. They saw it as a mandate to keep sprawling and spending to attract new people and to penny pinch quality of life issues in the city’s major existing neighborhoods, including downtown, the north and south valley, and Nob Hill.

As political scientist Richard Fox put it in a Mercury interview recently, American politics has become divided into those who pretend we live in economic markets and those who believe we live in human societies. In the l974 election here that stark difference was beginning to form and harden.

Before l974, Albuquerque had been run by a commission and a chairman who served as an ex-officio mayor. Soon-to-be-Senator Pete Domenici played that role in the late l960s.

In an effort to break the hold that winning slates of candidates had on city government, controlling everything until the next election, voters approved a new charter with a districted council and an elected mayor. Voters still kept the charade of nonpartisanship. But everyone knew who belonged to which party and what their policies might be. And we still do, of course.

The l974 election was all about growth and how to manage it. It was a battle between passionate constituencies -- The election took place not twenty years after the worst drought on record had lifted abruptly in 1957. Official Albuquerque still thought the city sat atop a vast lake of water, comparable to Lake Superior. And some politicians wanted the city to grow fast and furious, west into the hinterlands, and to compete with Phoenix and Denver as a major hub of the mountain and desert West.

Harry Kinney was an engineer at Sandia Labs, an associate of Domenici’s and a stalwart Republican. Herb Smith was a city planner well versed in cost benefit analyses of growth. He was the last City Manager under the old system.

One of the great circus events in modern Albuquerque’s political history was when three Republican members of the old City Commission teamed up to fire Smith as the City Manager, some two years before the mayoral election. The Commission chamber that night was packed with a huge crowd of partisans jeering and shouting. I think it was that night that Smith got the idea of running for mayor.

The interval between Smith’s firing and his loss to Kenney was one of the richest periods of policy debate we’ve ever had here. Smith had the audacity to suggest that developers pay the city for the roads and the public services their tracts of houses might need. He suggested that taxpayers really didn’t need to subsidize private development. Kinney ran on the slogan “the right kind of leadership” – the leadership of the status quo, of growth at any cost.

Smith built a coalition of environmentalists, social and economic justice advocates, UNM faculty and their families, preservationists, museum and arts advocates, and farmers and horticulturalists up and down the mid-valley.

Smith’s defeat was a crushing blow for people who thought a clean and verdant environment was the bedrock of abundance, and that forcing voters to pay for the despoliation of open spaces and regions near the Bosque by developers was an insufferable outrage.

To his credit, Kinney was a strong supporter of museums and the arts, but his engineering aesthetic and his antagonism to controlled growth and landscape and water conservation cost him the next election when progressive David Rusk defeated him soundly, appealing to the old Herb Smith constituency who rallied to his candidacy with a vengeance. Rusk, himself, was defeated in the next election by Kinney and a proto-Limbaugh talk show host Gordon Sanders. Kenney won the runoff in l981.

City politics have really never been the same. The old controlled growth coalition got burned out. The status quo came to offer candidates from both parties who wouldn’t rock the boat, including Mayor Ken Schultz, a Democratic sprawler-on-the-make who ran the city in the mid l980s.

Would that we had any passion at all in this year’s city election, or even a faction or two battling it out, or some long range perspectives on policy and philosophy to debate. Here we are at the precipice of what could well be a drought of such persistence that Western cities might be forced to raise water rates so high that their population sizes might shrink and some businesses go under.

But there’s been no talk about water in this election. And the mayor’s race, as well as the composition of the city council, could hinge on a single, remote issue in the north valley – a roundabout at Candelaria and Rio Grande -- and the ire it has raised.

Critters We Have Known - Badgers

Chaco Canyon can change your life in many ways. If you’re fortunate enough to encounter a totem beast in badger form there, your life might double back on itself and bring your childhood alive again when you’re old and flying high on sleek, if creaky, wings.

Badgers are the essence of ferocity and ambling self-assurance. Nothing budges them and if something tries, they turn on it with their two inch long claws and fierce teeth grinning viciously at the ready. But they’d rather stroll along, when they’re not digging for prey, moving with a waddling lilt oblivious to everything but their own subtle pleasures.

On the road from Pueblo Bonito to Casa Rinconada in Chaco Canyon, I came upon a great waddler of badger so long ago it seems to have been in mythological time. This Mr. Badger was much bigger than their normal 20 pounds. He was old and grizzled and moving along right down the center of the road. When I moved closer to give a little urgency to his gait he turned his head and hissed, his big furriness daring the Honda to take him on. He continued on his path, slower and more grumpy than before, until a curve in the road. He wasn’t about to make the curve himself, it seemed too much trouble for him, so he kept straight ahead moving into the open land around him.

For a brief moment behind that badger my memories gyroscope was tumbled out of the present into the first time my mother read to me Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, and showed me the Arthur Rackham illustrations of Mr. Badger in his warm robe and slippers welcoming Mole and Rat in from a winter storm for a good night’s sleep in his larder and breakfast in the morning. From that moment on, Badgers took on an air chivalry. Much like rough and tumble knights, tough and no-nonsense types that would happily lop off the heads of dragons, while doing good deeds and saving ladies, and anyone else, in distress. The myths of childhood remain with us all our lives, not frozen in interpretations, but evolving into whatever series of moments we are lucky enough to live though or inhabit.

The bookplate my wife designed for me one Christmas has a badger in his warm robe and slippers reading in a big easy chair by a roaring fire, and across the way one sees the winged feet of another reader, a mercurial one, probably puffing a pipe.

Badgers are known to be fastidious housekeepers, burying their droppings and grooming themselves like house cats. But they’re also hunting partners, some contend, with coyotes, and thereby earn something of a trickster patina by association, regardless of how slow and grumpy they remain. Coyotes know that badgers are a special foe of rattlesnakes. They’re impervious to their bites, except on their bare noses. When hunting them, a badger apparently tries to entice one to a strike. I can see the badger grab it as it hits the ground. The coyote waits off to the side, and takes hold of the tail when he can as the badger’s massive jaws make short work of the snake’s head.

If the coyote should turn on a badger in exasperation at a failed hunt, the badger can dig himself a cave so fast it makes ears go up in amazement. And once he’s in far enough, Mr. Badger turns around and presents that threatening toothy grin to his former hunting mate. No coyote in his right might mind would risk taking on a badger who’d removed his robe and slippers, ready for a fight.

Any place, of course, can change our lives – dark winter woods looking for Badger’s house, or the sandy shores of ancient seas where Chaco is to today and where badgers dig their oblong dens in dunes that might release a shark’s tooth or a fish spine from when New Mexico was under water.

(Creative Commons images via Flickr. Estancia ranch by John Seb Barber, Quarai ruins by BriYYZ, Albuquerque aerial by Mr. T in D.C., Badger by canopic.)

August 26, 2013