Political Protests and their Dangers

The striking photo by William Aranda in the Mercury this week of tear gas, in the twilight, spreading up Central Avenue across from the UNM Bookstore and the School of Architecture and Planning had that feeling of being at once a timeless and universal image of reactionary crudity and a fugitive moment of protest by ordinary people who just couldn’t stomach injustice any more.

That moment of rage last week over police brutality by the APD ran over the edges of time into moments of rage many decades ago at an undeclared war that would eventually claim the lives of over 58,000 American soldiers and as many as 3.8 million Vietnamese.

Thank heavens no one was seriously injured or killed in our recent protests. Given the violent proclivities of police these days and the deterioration of our culture’s Constitutional values, I worry that might not be the case in the weeks ahead. It certainly wasn’t that way in the l970s when great harm and injury was done to people who were exercising their constitutional right “peaceably to assemble, and petition Government for a redress of grievances.”

In fact in all the protests at UNM and in Albuquerque over the decades the vast majority of injuries and harm have been caused by the Government which was being petitioned to redress grievances. Violence against innocents, in one form or another was, of course, the usual grievance to be redressed.

With a trigger happy police department like ours today in charge of “crowd control,” I worry that the killings that have befallen our communities might also be visited upon protesters exercising their consciences and constitutional authority as citizens.

In the early 1970s far too many people here paid a personal price in pain and near fatal injury simply for speaking out in non-violent assemblies. They caused trouble for the status quo, and such trouble often turns the First Amendment into a document written in invisible ink. The l970s were a chaotic time in our country, but one that was not bristling with guns and police officers who apparently think nothing of dispensing permanently with troublesome homeless people.

There are few good accounts of the troubles at UNM in the early 1970s when Jane Fonda and Alan Ginsberg spoke their minds on campus about the war in Vietnam. One of the better renditions we have comes from former UNM President Bud Davis writing about his predecessor President Ferrel Heady whose fate it was to deal with the repercussions at UNM from the 1970 murders of four Kent State students protesting Nixon’s escalation of the Vietnam War. Davis’s history of UNM, Miracle on the Mesa, is still in print.

The National Guard at Kent State opened fire on protesters, not only killing four of them, but wounding nine more, some of whom were paralyzed. It was looked upon as a massacre by students across the nation. Davis wrote that some called what happened afterwards at UNM “the most savage event in the University of New Mexico’s history.”

Depending on the account, ten or eleven people were bayoneted by New Mexico National Guard troops who were holding a perimeter around the occupied Student Union Building during a heated, but nonviolent, demonstration over Kent State and the war.

To their undying credit, the young teargas masked troops, who many reported were extremely nervous finding themselves in such a position, did not fire into any crowds. But when students and news people got too close, they panicked and lunged at them with unsheathed bayonets. One of the wounded was a former student of mine who was a TV newsman at the time. I was on campus to see what was going on when I met him running with his camera to get some footage for the evening news. He got too close to those bayonets and was stabbed in the thigh. He came running toward me yelling he’d been stabbed. Blood was seeping through his pants and running down his leg. A professor and some students helped him to the ground. The prof took off his tie and made a tourniquet. The news cameraman survived, a scar on his leg and in his memory, I’m sure.

The worst “incident” of that period came when some 150 protestors closed off I-25 near what’s now the Martin Luther King Jr. overpass. Traffic was halted for a while by a barricade across the road. Albuquerque Police arrived, not the National Guard, and fired teargas into the crowd. Then something happened that was horrendous, and largely under-reported. The police shot into the crowd, wounding two people, one of whom was a young women reporter from the UNM Daily Lobo who was blasted in the chest and stomach with buckshot from a shotgun, fired at a considerable distance, so it left her “only” covered with terribly painful little holes. She survived. But this was no “beanbag.” This was the real McCoy.

If such things could happen in l970, they can certainly happen in an age where there are enough guns around to arm every man, woman, and child in the country. And now, as then, every crowd of demonstrators has it police spies and snitches, and its agent provocateurs stirring things up, hoping for some rupture in civility to open up and allow teargas, Tasers, and much worse to slam into unarmed people of conscience like a cannon ball.

So, “Let’s be careful out there,” as the Sergeant used to warn his officers in the 80’s police series Hill Street Blues. This is Albuquerque 2014. And this can be a very dangerous place.

The Real Lowdown on Radiation and its Impact on Human Health

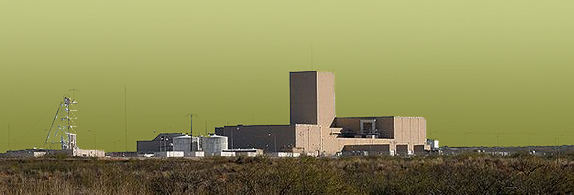

In l991, the Albuquerque City Council declined to alter its waste water ordinance to allow Sandia National Laboratories to dump 50,000 gallons of “low level” radioactive waste water into Albuquerque’s sewer system.

The debate at the time mirrors the language, contradictions, and tangled accusations and denials that have kept New Mexicans confused about the leak into the atmosphere of radioactive materials from the Waste Isolation Pilot Project (WIPP) north of Carlsbad nearly seven weeks ago. It is still uncertain how much radioactive material was released or exactly how dangerous it is. We do know, though, that the leak was thought to be an impossibility and was never supposed to happen -- ever.

In l991 Albuquerque Tribune environmental reporter, Tony Davis, wrote a piece with the headline:

He laid out the controversy over Sandia’s request to dump what it claimed was highly diluted radioactive waste water into our water works, a practice that the city had allow hospitals to do for some time.

In the piece he quoted two medical doctors from New Mexico Physicians for Social Responsibility (NMPSR). They put to rest for me all the arguments and obfuscations about the risks of exposure to radioactivity. As an international organization, Physicians for Social Responsibility won the Nobel Peace prize in 1985.

Davis quoted Dr. Dan Kerlinsky who was then president of NMPSR. Relying on the old saw that the “solution to pollution is dilution” is a dangerous fallacy. Davis wrote that despite Sandia Labs’ assurances to the contrary, “Others say there’s no known safe level of radiation. Even a small addition is bad,” Dr. Karlinsky told the Tribune. “It not like alcohol poisoning the liver or brain, where a little alcohol poisons a little and a lot poisons a lot. With radioactivity, one atom is the unit of production of cancer….if it is in the right place….You can’t say that one atom won’t produce a cancer and two atoms will. It depends on whether radiation happens to hit a piece of genetic material.”

Tony Davis quoted another member of NMPSR, Dr. Ted Davis, an expert on radiation issues who contended that “mathematical models for determining how much radiation humans would get from drinking this water never have been proven valid.”

“These modeling methods are 5 and 10 years old,” Dr. Davis said. “If a material stays radioactive 10,000 years, how can you do experiments to show what happens over 10,000 years or even 100 years. It defies human logic to think that if it takes maybe 100 years for plutonium to get concentrated into plants, that you could have a model (for that activity) that’s been validated.”

The same holds true for WIPP’s radiation release. There’s no way to test, or falsify, or validate the long range impact of that release, especially as we don’t know, or have not been told, how much leaked out of the half-mile deep salt repository which holds some 170,000 barrels of low-level transuranic waste. It’s also been something of a sleight of mind, once again defying human logic, to contend that the material in WIPP is low level waste and therefore not dangerous. How could that be if it has been buried in a specially constructed salt mine that is 2150 feet below the surface of the earth? If the hammers, booties, hats, goggles, and other articles of apparel stored in those barrels aren’t dangerous, why not just use them again? Well, it must be because they are dangerous.

This discussion of risk is the great circus juggling act of nuclear science and its opponents. Even after seventy years the producers of bombs, and the nuclear waste that comes with their manufacture, are denying any real public health risks associated with their efforts. Their denials are dauntingly similar to the denials of the fossil fuel industry about its contribution to global warming and climate change, and the tobacco industry’s endless assertions that there’s no evidence that its product is the direct cause of cancer and other ailments.

For those of us who are skeptical of the federal agencies and the military-industrial complex that operates WIPP, it’s good to look beyond New Mexico’s borders for answers. The Washington State Department of Health (WSDH), concerned as it is with the vast amount of nuclear waste at the DOE old plutonium manufacturing reactor and plant in Hanford. A WSHD report on the dangers of exposure to low-level waste quotes British scientists who have been keeping track since l974 of low-level radiation in children living around nuclear power plants in England. Dr. Alice Stuart, a senior research fellow at Birmingham University in England, is quoted as saying that “constant, low levels of radiation are relatively more harmful than higher levels of exposure over a short period of time….There is increasing evidence that the risk of cancer is proportionately greater at low doses….Internal radiation doses from contaminated food and water over a long time appear to damage the body much more than the same doses from short external exposure….Whether internal exposure will result in a cancer that spreads to other parts of the body depends on the ability of the immune system to detect and destroy the cancer cells.” The WSHD also quotes Gregg S. Wilkinson, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. A person with a weakened immune system “might also have developed a cancer from radiation exposure. By not accounting for deaths from weakened immune systems, current risks of cancer deaths from radiation exposure underestimate the harmfulness of radiation.” According to Wilkinson, the high incidents of embryonic cancers around the world, discovered by the Oxford childhood cancer study, might well increase even further by the addition to background radiation of long-term, low-level radiation released by nuclear defense facilities. [Orphaned Land, p. 193}

If the tremendous amounts of hazardous waste from nuclear bomb manufacturing and the equally huge amounts of waste from commercial nuclear power plants is ever to be stored safely, the first step must be a public acknowledgment of the health risks of exposure to low-levels of radiation. This might cause momentary panic, but it’s my bet that such panic will easily morph into the political will to seriously work to solve the problem and not just give lip service to doing so.

Instead of always muddying the water by denying risk, and then having their denials challenged over and over again, the nuclear industrial complex and the federal government must own up to the mess we’re in – if it really wants to protect us all from the potential damage to human life that nuclear weapons and radiation from power plants brings.

Benjamin Sacks (1903-2007) and Second Chances at UNM

Dr. Benjamin Sacks, or Gunny Sacks as he was affectionately known to some of his students, taught history at UNM for over 30 years. He was one of those rare professors who understood that teaching was a lot like coaching. You coach a kid in a sport trying to help him be his best and contribute the most he can. It should be the same in the classroom.

As young college students at UNM in the l950s many of us who would turn out to be late bloomers thought that Dr. Sacks was one of those professors who actually did want the best from us and for us. Many professors then at UNM were like that. But many, as well, were like they are today. It’s what I’d call studentphobic. They don’t like their students. They find them constantly lacking. And they think that a 20-year old who’s not doing well will turn out to be that same intellectual ner-do-well all his life. There are no second chances in their lexicon. If freshmen students can’t cut it on their own, then fail them so they won’t be a “burden” on the system.

Not so for Dr. Sacks. He taught us how to learn.

Maybe his long experience early on as a basketball and football coach helped to make him a great teacher. Maybe his decades as an athlete himself, as New Mexico’s master handball player, gave him insight into what it takes for students to devote themselves to self-improvement. And I’m sure that was his ultimate goal – to help them get better at learning and thinking. A good teacher coaches students in the art of making sense of the world and of a discipline.

He knew instinctively that in his huge freshman history classes there were a good number of young people who wanted to do well, but who didn’t know how. And instead of complaining about them, he taught them the tricks and skills of the trade.

The most important of those is summed up in the motto of all people who know how to perform at their best – over prep. To be overly prepared is to allow yourself to relax in the knowledge that you have done your best in any given situation and allow yourself to perform your task – be it learning or expressing what you’ve learned – without anxiety and its blinders.

Dr. Sacks gave his students a mental workout program when he said in all seriousness, “if you want an ‘A’ read your notes every night.” This is the law of mental accumulation. Take good notes, read them over and over. The more notes you take the more you have to read and remember. The more you read and remember the more curious you’ll become and the more curious you become the better student, the stronger student, the more agile student you will be.

Like all coaches he pushed us. He gave us a way to work hard and work harder without cracking the whip, which everyone soon enough rebels against. Most of his second tier students knew they weren’t very good at learning. But when they followed his advice, they learned they were better than they thought – even “A” material, if you will.

Dr. Sacks knew that giving a kid – an ill prepared kid -- a chance in college was giving him a second chance in life.

And I, for one, will always be grateful to him for helping me turn my life around.

April 08, 2014