The Disappearing South Albuquerque Works

One of the most important monuments to Albuquerque’s environmental history suddenly disappeared a couple of years ago. The immense factory that is no more was located in the South Valley on top of a major Superfund site, and in an area with the most polluted groundwater in the city. The factory site was owned by General Electric and had been used in the manufacturing of jet engines.

A landmark in the South Valley for well over 65 years, the factory was there one moment and then, quite literally, gone the next, utterly vanishing with no traces left behind and no mention of what happened in the local news that I’m aware of. This wasn’t just some old factory structure. It had been the South Albuquerque Works, a key location in the role that New Mexico played in the Cold War arms race. And in 2006 it was the site of the largest environmental law suit in New Mexico’s history when the state sought some $4 billion from General Electric, then owner of the site, for polluting the ground water.

Very near a Hispanic neighborhood called East San Jose, the factory had been on Woodward Avenue between Second Street and Broadway since the late l940s. In l952, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) took over the plant from Eidal Manufacturing where one of the AEC’s subcontractors, American Car Foundry (ACF), had been conducting, according to the Albuquerque Tribune, “a secret project” for the AEC. “Details of the work are ‘fully classified under the restrictions of the Atomic Energy Act of l946.” (Orphaned land p. 123) Five years later in l957 the Tribune reported again that the ACF plant formerly belonging to Eidal did “top secret manufacturing” but could say nothing more.

The factory was known as the South Albuquerque Works and was one part of a triad of facilities that included Los Alamos National Labs and Sandia National Labs.

According to the Tribune the South Albuquerque Works had as many as 1000 employees and worked on “nuclear reactors, missile components, airframe machine tools, classified Atomic Energy Commission products, detection devices and counter measures, flight simulators and training devices, ordinance and components of radioactive materials, handling systems, and weapons handling equipment.”

In l958, the AEC’s South Albuquerque Works was involved with the development of Project Rover, a nuclear powered rocket engine. The South Albuquerque Works was “fabricating a portion of an experimental reactor for nuclear propulsion under a subcontract to the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory.”

The Tribune interviewed a Brigadier General named Alfred D. Starbird who characterized the South Albuquerque Works as “one of the three major New Mexico facilities of the [Atomic Energy] Commission’s weapons complex….Naturally there is an extremely close coordination between activities of the South Albuquerque Plant and the other two facilities.”

In l967, after Project Rover’s engines were tested successfully in Nevada but then tabled for unknown reasons, the Air Force purchased the factory site from the AEC and contracted with General Electric (GE) to produce jet engines there. The Air Force sold the Plant to GE in l984, well after a plume of contamination was discovered under the plant in l978. That plume eventually caused the closure of two city drinking water wells and 16 or so private wells on the southern edge of the East San Jose neighborhood. It wasn’t until 1983 that the GE site, at the request of the New Mexico Environmental Improvement Division, was placed on the National Priorities List as a Superfund Site. It took five more years, until l988, for the Environmental Protection Agency to come up with a plan to clean up the mess. The plan was a mix of “soil vapor extraction” and “pump and treat systems,” similar to those now being employed or proposed for the gigantic Kirtland Air Force Base spill of 24 million gallons of jet fuel.

By the time the state of New Mexico sued GE over the contamination under the old South Albuquerque Works, GE had already spent more than $93 million over ten years to clean it up and looked forward to 20 more years of effort, which would result in cleaner water, but water that would not be suitable for drinking. As the New Mexico Environment Department said on its website in 2009, ground water pollution can’t always be cleaned up. “Once contaminated, ground water is difficult or in some cases, impossible to return to its original quality…. Restoration of ground water quality often takes decades to accomplish and can be very expensive.”

In the State of New Mexico’s case against GE, and some 100 other companies, the state’s chief witness, Jack V. Matson, professor of environmental engineering at Penn State University, observed that GE, and its predecessor ACF, stored liquid waste in underground tanks, “discharging effluent to the San Jose Draining Ditch, spraying oil mixed with solvents on the ground for dust control, and burning oil mixed with solvents in open pits.” Given the “abundance of literature on the effect of disposing wastes into ditches and onto the ground, ACF/GE should have known that many of their disposal methods could negatively impact the environment…. Chemicals such as solvents and oils are easily recoverable, and the technology has been available since at least the early 1920s,” Matson said.

To make a long story short, little of which was covered in the mainstream media, the state lost its case to recover damages for its lost water because a U.S. Federal District Court judge was persuaded that the clean up efforts would restore the water to a usable, if not a potable state, saying the water could be used for fire protection and agriculture and was, therefore, not permanently or completely impaired. No one was quite sure what that meant considering the dangers of using partially contaminated water to grow food and that same water, still contaminated by small amounts of industrial solvents, to fight fires. No one thought to question how one might get to that particular plume of partially clean water in the South Valley to fight fires even in the near vicinity. Did the judge mean for us to siphon it out?

Having written a book on New Mexico’s environment since the Manhattan Project, The Orphaned Land, and reporting on such matters for many news outlets over a number of decades, I often enjoyed taking curious and like-minded people to see the infamous Superfund site and the old home of the South Albuquerque Works. One day in 2011, I took a colleague who was designing digital environmental learning games to Woodward Avenue so he could photograph it for one of his projects.

And, lo and behold, it wasn’t there. I drove back to the intersection and checked the stop sign to see if I was on the right road. I was. In what amounts to a blink of an eye, a 700,000 square foot manufacturing plant that had been operating there in some form for over 60 years, a major monument to New Mexico’s status as a Cold War nuclear sacrifice zone just simply vanished, and all its secrets with it.

Then, to my astonishment, I found, quite by accident on the EPA’s website, a story about the “green demolition” of the General Electric Aviation division demolishing its plant probably a few months before I made my last attempt at a visit. GE had closed the plant in 2009, but had left it standing for two, presumably empty, years. The EPA green demolition write-up was, in fact, actually commending GE on its recycling of the building, saving “14,280 tons of building and related materials from being sent to local landfills.”

The EPA said that “GE Aviation first removed all hazardous materials, including chemicals, oils and coolants, asbestos-containing materials and universal wastes such as light bulbs, and disposed of them according to all applicable federal, state, and local requirements.” Of course that does not include the pollution in the ground water, unless GE magically invented a new decontamination process. The demolition and removal of the waste took from January to April 2011. “Once completed,” the EPA wrote, “nearly 85 percent of all building materials had been set aside for reuse or recycling….After demolition, the only materials that remained were piles containing unusable materials such as insulation, sheet rock, and wood framing debris” … and the pollution in the water under and near the plant! The EPA, which administers the Superfund and knows full well that the groundwater clean up isn’t even half done, failed to mention that prominently in its little encomium to GE’s “green demolition.” In fact it went on to say that “Looking forward, GE Aviation might sell the property where the demolished buildings once stood.” The only place where the EPA mentions the site’s water pollution issue is here: “Although residual ground water contamination might require certain use restrictions on the property, building demolition paves the way for a new developer hoping to take advantage of the property’s excellent access to the airport and major transportation corridors. With good fortune, the property could soon become home to another critically important employer for Albuquerque and Central New Mexico.” As someone’s grandma used to say, “saints preserve us.”

Sleepless Against Climate Change Denial

When 30 Democratic Senators, including New Mexico’s Tom Udall and Martin Heinrich, held an all night vigil on climate change last week to try to do something to break the intellectual, political, and moral log jam on greenhouses gases, the Republican party responded like this: It’s just a publicity stunt. It’s just a way to get campaign contributions. They’re just talking to themselves.

Well, it’s a lot more than that, though it’s not, I know, a well constructed, ongoing campaign of potential legislation. It’s not a set of problem solving proposals to move from fossil fuels to renewable energy while helping workers in one industry transition into the new one. It’s not a set of proposals to protect coastal America, east, south and west, from rising ocean levels. It’s really nothing more than 30 highly political people putting themselves on the line against climate change deniers and the industries that support them. And they did so in a dramatic way designed to focus attention on this “defining issue of our generation,” as billionaire California hedge fund manager and strong supporter of climate change recognition and legislation Tom Steyer has said.

There has to be much, much more than dramatic moments and sleep overs in the U.S. Senate, of course. But this one symbolic act probably gave more credibility to the issue of greenhouse gases and the erratic, and often catastrophic, weather that comes with them than any purely political action has in years.

This was 30 Democrats in the U.S. Senate, the bastion of settled mainstream American values and conflicts, the bedrock of our political stability even when it is riven by irreconcilable differences. The system and its structure endures all manner of conflict. It is the ballast of American political life. Senators, next to governors, are the most influential people in their states, if they play the system properly. They deliver the goods.

And Tom Udall and Martin Heinrich delivered the goods, ethically and politically, on climate change and greenhouse gases last week, even as representatives of one of the greatest oil and gas producing states in the nation. They did the right thing. And I, for one, am proud of them and grateful to them. The Senate all-nighter was a textbook moment in the history of response to climate change. Perhaps it will prove to be a fine-print footnote, but it’s there.

Most of the world that hasn’t been brainwashed into blithering idiocy by the PR machine of the fossil fuel industry knows that oil, natural gas and coal are the major contributors to global warming and climate change. They also know that the climate troubles looming are the greatest natural, or unnatural, source of human misery ever to afflict humankind’s habitat. They connect the dots: terrible drought in the southwest, wild floods in the Rocky Mountains, at least three 1000-year floods in the Midwest last year, calamitous hurricanes on the east coast, and similar events around the world, including hurricane force winds in southern England and much more over recent years.

Those in politics who can’t, or won’t, connect the dots tend to be defenders of the fossil fuel industry. And they often mouth the industry’s PR language and rationales, the same kind of logic that most people now know was employed by the tobacco industry to ward off the Surgeon General’s warnings about the role smoking plays in cancer, heart disease and breathing troubles. They trump up scientific controversy over climate change, where there isn’t one. They fret about damaging the economy “for no reason,” they say, when what they’re really worried about is their own corporations’ profits and the trillions of dollars worth of oil and gas still in the ground that could be theirs. And they will do anything, even to the extent of perhaps causing the death and misery of untold numbers of people to preserve their right to all that money.

Then there’s 30 U.S. Senators, not a Republican among them, who, at some risk to their own political careers, take the drastic step to say the Emperor Has No Clothes. I hope they pull off this little “stunt” three or four more times this year, particularly after another climate disaster. Perhaps we’ll see one or two more Senators join their ranks, perhaps even a Republican.

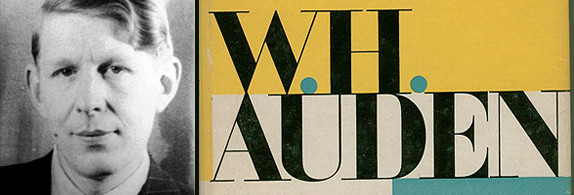

W.H. Auden in Taos, 1939

1939 was not a good year for humankind. WW II began in September. By its end 60 to 85 million people around the world would be dead. Of the 16 million Americans who would serve in the war, some of them in l939 must have started to do some contingency thinking. Few would have suspected that they might be among the 405,399 Americans killed in combat.

On September 1, Nazi Germany invaded Poland. A few months later, W.H. Auden, a radical English poet who was acknowledged by many to be the greatest craftsman of his day, finished writing in Manhattan what would become his famous poem “September 1, 1939,” a poem much loved and much quoted, despite Auden’s own eventual dislike of it, as it seemed to him to be self-flattering.

Writing of “a low dishonest decade” in which “The unmentionable odour of death/Offends the September night,” Auden in the last two stanzas of the poem observed:

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out everywhere the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair

Show an affirming flame.

A few months before “September 1, l939” was written, Auden and his partner the poet Chester Kallman “honeymooned” in New Mexico, to quote Auden, during a cross-country bus trip from New York to Los Angeles, traveling to visit Auden’s long time friend and collaborator Christopher Isherwood. There’s some suggestion in various sources that Auden and Kallman rented the cottage that D.H. Lawrence had lived in more than a decade earlier on what is now known as the D.H. Lawrence Ranch east of Taos. One reference mentioned he might have rented the cottage from the writer’s wife, Frieda Lawrence herself. Lawrence had died in l930 in France of tuberculosis. Frieda had remarried and lived on the Lawrence Ranch. She built a Chapel where Lawrence’s ashes remain to this day. It seems likely that Auden and Kallman visited the shrine before they traveled on even knowing as they must have, about Lawrence’s misanthropy, his anti-democratic passions and general far-right political views that were so antithetical to their own.

At the time, Auden and much of the rest of Europe saw the Nazi threat advancing. Who knows what Lawrence would have thought. But as Auden wrote in “September 1, l939”

I and the public know

What all school children learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About Democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analysed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief;

We must suffer them all again.

Auden became a naturalized American citizen in l946 one year before he published what is perhaps one of the five or six signature poems of the first half of the 20th century, The Age of Anxiety.

He had left England just before the war. His critics there lambasted him for leaving the home front. He had tried to come back and join the British forces, but was considered by the government too old and unessential at 32. He tried as well to enlist in the American army but was rejected for health reasons.

He had spent time in Spain during the early days of Civil War in l936 or 1937 as an ambulance driver for the anti-fascist forces of the Republican Army along with other British citizens, including George Orwell, associated with what was called in Oxford the Auden Group. Auden left Spain disillusioned by the violence and atrocities practiced by both sides in the war. In his poem “Spain” writing of these experiences, he said:

To-day the deliberate increase in the chances of death,

The conscious acceptance of guilt in the necessary murder;

To-day the expending of powers

On the flat ephemeral pamphlet and the boring meeting….

The stars are dead. The animals will not look.

We are left alone without our day, and the time is short, and

History to the defeated

May say Alas but cannot help nor pardon.

After WWII had ended, Auden volunteered to survey the destruction of German cities wrought by Allied bombing. It was then, it is believed, that he learned of the death of anti-Nazi theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer who had been implicated in an assassination attempt on Hitler and hanged by the Gestapo just before the end of the war in l945. Auden’s own Christianity took on a more activist role after that as has been described in an inspiring article by Auden scholar Edward Mendelson entitled “The Secret Auden.” Mendelson describes Auden’s charities and endless generosities to people in need, friends and strangers alike. “He kept it secret because he would have been ashamed to have been praised for it,” Mendelson wrote.

When Auden and Kallman left Taos continuing their bus journey to Santa Monica, California, to visit Isherwood, they must have driven passed the Jemez Mountains coming down to Santa Fe. They had no way of knowing, of course, as nobody did, that three years later those mountains would hide the Manhattan Project. But when Auden’s long poem, The Age of Anxiety, had been published, readers understood exactly what that anxiety was about, having suffered most likely from the horrors of the Holocaust and Hiroshima in their dreams. The anxiety was about a world of people no different from those who just a few years ago had slaughtered 60 to 85 million of their fellow humans, often with enthusiasm, a world of people who were now armed with weapons of mass destruction, destruction potentially so vast that one moment of psychosis or rage in the wrong person could see a whole world in which “All the stars are dead” for us.

And so it has been since 8:15 a.m. August 6, l945. As Auden said, “Now is the age of anxiety.”

March 17, 2014