Who is Credible and Who is Not?

The principal question in the information age is whose information is credible. For those of us who deal in nonfiction as journalists, independent scholars, essayists, or columnists and their readers, knowing who to believe and why is the first and ongoing task in any project. We’re not speaking here of a search for truth, but rather for a credible version of the truth, one that, as philosopher of science Karl Popper would have said, can be “falsified” or tested. One version, in other words, that isn’t gospel set in stone.

Is the harmlessness of “fracking” a credible or “falsifiable” reality when it is asserted by those whose business it is to make money from fracking? Is education reform involving endless testing credible when it is supported by leaders who’ve received electoral backing from companies who profit from testing? Is the supposed purity of the concept of supply and demand credible when it’s asserted and set in stone by economists who use it as an excuse to explain income inequality?

To know whose version of a particular issue is credible to you, you must first, of course, understand your own biases, predispositions and world view. Everyone has a slant, and a slant is what focuses one’s view of the truth, though it probably won’t determine it if you’re blessed with an open mind, but one that’s not so open that your brains falls out, as the poet Marianne Moore used to joke with caution.

So when you’re researching or studying the “free market” and the law of supply and demand, or fracking, or the best way to help children learn, you will inevitably be faced with controversy and contradiction.

E.F. Schumacher in a profoundly useful book, A Guide for the Perplexed, cites two kinds of problems, what he calls converging and diverging problems. The unscrupulous try to confuse the two. Convergent problems are largely technological. For instance, what’s the best way for a person to cut a single sheet of paper. The answers tend to converge and point to an instrument with a sharp edge, like a razor, or an instrument with two sharp edges that cross each other like scissors. A divergent problem has no single answer that tends to be agreed upon. The answers diverge. Take the problem of how best to educate a child. Chances are there as many answers as there are people. The answers may diverge into numerous categories, but they are different and conflict.

Anyone who tells you their answer to a divergent problem is the only way that works is in my book not credible. And anyone who says that because there are differences a problem is not convergent is, likewise, not credible. Take climate change for instance. Assessing the truth of it is a convergent, technological problem, not a divergent one with an array of differing opinions. The answer has converged around computer models that an overwhelming body of thinkers find credible with current events backing up their predictions every day. It’s not like the best way to cut paper, of course, but the solution to the problem of assessment has converged. But what about those who don’t agree with the notion of climate change?

Their numbers are so small – in the scientific population no more than three percent – that they do not constitute a divergence but an opposition. They’re roughly like the folks who hold out for cutting paper with a small flame rather than with sharpened blades. They may be passionate but, practically, they are wrong

It might be said that fracking is technologically a convergent answer to the problem of how best to get certain kinds natural gas and oil out of previously inaccessible geologic formations and conditions. But if advocates of fracking technology, which is convergent as far as extraction is concerned, then try to say that it must be convergent when it comes to clean water and the health of surrounding populations, they are blowing smoke you know where. And that’s because determining the health impacts is a divergent problem, and technological drilling experts are obviously not health experts. So their pronouncements may be trustworthy when it comes to extraction but worthless when it comes to health. And I would have to say that health experts who work for drilling companies lack reliability as well, for obvious reasons.

Just as researchers have to be aware of their own biases and predispositions, they must also become aware of the angles and slants and world views of experts and scientists who are, of course, human beings and lean one way or the other like the rest of us. And unhappily, for those of us who are looking for credible versions of the truth to use as working hypotheses, we must always be aware that science and expertise for hire tends to slant in the direction of those who are doing the hiring and paying the salaries.

Would you, for instance, ever hear a tobacco company scientist or a fracking company scientist say that their products and processes may indeed be harmful to human health? No. You might hear former employees say such things, but they might be branded whistleblowers and tarred and feathered as they’re ridden out of town on a rail.

For myself, I tend to trust independent scholars and researchers in NGOs more than I do scientists and experts for hire. As a researcher I would automatically dismiss reports in professional journals or media outlets of the opinions of, say, a physicist or a nuclear engineer on the health effects of certain kinds of radiation. It’s a trick that’s often used to dupe the unwary. Physicists and nuclear engineers have no expertise at all in the area of personal and public heath. They are not medical doctors. They are not experts in any of the highly specialized fields of medicine. They are physicists and engineers, often times bomb makers, not neonatologists or gerontologists.

Needless to say, experts are experts in their fields, but not in everything else.

Let’s look at a sacrosanct view of economic theory, supply and demand. Is it a convergent or a divergent solution to a particular problem about why goods are produced and moved around they way they are? I would say that “supply and demand” is a divergent idea serving certain political views that would like us to believe it is a universal law of how the world’s economy actually works because it makes it easier for them to monopolize profits.

Yes, supply and demand is an interesting formula for understanding some kinds of price fluctuation. But as a theory of truth, it doesn’t sync well with reality. Goods and services are not produced only in response to “demands” and “needs” for them. One can see how silly such a thought is when examining products on the cereal aisle in the supermarket. What pure demand was there, do you think, for Lollypop Doodle Marshmallow Crunch Clusters or some such other delight? What kind of pure demand was made known to supply children with smart phones? There was none.

The impurity of supply and demand has to do with the creation of false demand which leads to the creation of what we come to see now as our utterly frivolous economy, flooding the market with cheaply produced high-end goods, let's say, that do not lower prices, only wages. Creating a false demand for products cheaply produced abroad contributes to the ruination of local economies whose workers are passed over in favor of people in other countries too poor to protest slave wages. The products of false demand are then sold back to those same passed over workers at a price they can ill afford to go into debt to purchase, though they often do.

It might be said that the theory of supply and demand is not a convergent idea about how the real world works, but rather a near universal law about how to con consumers into thinking their debt burden is an inevitable product of “market forces.” In a consumer economy, demand is rigged by advertising, which is itself a convergent solution for how to fleece people and make them demand products they do not need or know they want until stimulated by ads to desire them.

All this is, naturally, crystal clear to most people at some time in their consuming lives when they find themselves being conned into really, really wanting something they can’t afford but can possess through credit.

The con is endless. It applies just as well to people supplying natural gas to the world through hydraulic fracturing while claiming to the residents near their wells that not only will their health not be harmed by fracking but their nation will be energy independent, and yes, lots of money will be made by a few. Or conning a populace into believing that children who are taught to answer tests correctly, a process akin to cheating, will actually be educated and thrive in the world of competitive ideas, ideas which cannot be predicted by testing. And, yes, lots of money will be made.

The con goes on. The convergent answer to the problem of making people do what they do not know they “want” to do so you will profit from their actions is to scam them through advertising and other methods of enticement and persuasion, making them want, and even think they need, what had never crossed their minds before. What a way to run a world!

Richard A. Bice – 1917-2008

Dick Bice was the kind of man who you’d turn to if you needed a long and complicated project completed efficiently and even beautifully, with all the i’s dotted and all the t’s crossed . He knew how to get things done with hardly anyone, in the long run, knowing that he’d done it. It wasn’t in his makeup to take credit.

Dick Bice was the chairman of the Board of Trustees of what’s now the Albuquerque Museum, almost before it was a museum. I met him when I somehow was appointed to the board as a young journalist in the l970s. Even though he and I often held opposite political points of view and differing life experiences, I learned a lot from him, more than I probably knew at the time.

The secret of getting things done in meetings, he told me with that gentle smile of his, is to make the agenda. He who makes the agenda runs the meeting. And meetings actually can sometimes result in decisions that get impossible things accomplished. Dick Bice made the agendas, and stuck to them, year after year, agendas that helped found the Albuquerque Museum. Before him, it was an idea without a building of its own. The hiring of Antoine Predock to design the Museum’s first building in Old Town, which opened in l979, and the assembling of a brilliant creative staff lead by director Jim Moore, made our museum one of the best small museums in the country. It was, by and large, Dick Bice’s steady, quiet and focused leadership, both on the Museum Foundation and the Trustees, that got it done.

Dick Bice was the first of a long line of Sandia Lab engineers to sit on the Albuquerque City Commission, way before two-time Mayor Harry Kinney. Bice was a member of a ticket that ousted the politically powerful Democrat Clyde Tingley from the chairmanship of the City Commission in l953. Bice served for eight years on the Commission. He was instrumental in creating the city planning department, laying out the interstates through town, creating zoning for Winrock Mall, the first shopping center in the city that was completed in l961, and was an early backer of the San Juan Chama diversion which is now the Albuquerque Drinking Water Project. Bice was also in on the founding of the Archaeological Society of New Mexico, the Albuquerque Archeological Society and the New Mexico Museum of Natural History.

Bice moved to Los Alamos as a mechanical engineer in the Manhattan Project in l944, eventually setting up the Sandia Branch of Los Alamos. He retired from Sandia Laboratories after 20 years as a vice-president in 1978. Obituaries say he worked on field testing and “development engineering.” Sandia did critical work on nuclear weapons fail safe devices, and it’s nice to think that he might have worked on those, though, of course, he never spoke a word with his museum friends about his day job. And he never mentioned politics.

What I admire most about Dick Bice is the example he set for what a single person can achieve in the always tumultuous political environment of New Mexico. One could say that the times were ripe for a person with Bice’s organizational skills and broad interests. And that was true in post war Albuquerque. But as a publically engaged citizen he inspired others to deepen their own commitments to civic action. He was a citizen leader, not a party windbag or ideologue with delusions of grandeur. In my conversations with him about the museum we might different on specifics, but he always listened intently to me and to his fellow board members and never brushed any point of view aside. He dealt with conflict gracefully. But we always knew that he never took his eye off the prize, despite the swirls of controversy, and would never let the board be diverted from its goal to create a first class museum.

He was what a citizen should be. He took his role in society seriously, but never pompously. He was content to contribute and perhaps lead the way, but was never at the head of the pack taking triumphs where he could. Dick Bice was simply the kind of person you could trust personally and the kind of person who deserved and earned the public’s trust.

I’ve tried to uncover for myself what made Dick Bice such an exemplary civic servant. It’s not an easy task because he was so self effacing. But the nearest I can come to seeing a pattern that ran through his actions is this: he was focused intensely on the specifics of his projects not on what the projects might achieve politically. He was a museum man, through and through, an engineer and a planner, and an amateur archaeologist who brought honors to his love of learning and his passion for the past. His agendas were about what was best for the tasks at hand. He leaned to the conservative center politically. But politics and dogma were not on his agenda. It was a relief to know that such a person could exist in the practical world. And it was a mind opening gift to learn from him as you watched him work.

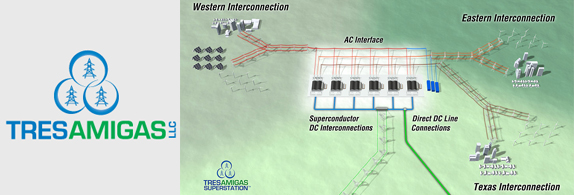

Tres Amigas

Somewhere near Clovis, New Mexico, in Curry County, a great experiment in renewable energy transmission is starting to take form. It’s called the Tres Amigas SuperStation. It is built on a 22. 5 square mile piece of land in the New Mexico portion of the Llano Estacado, a vast, flat plain that is so without geographic features that travelers were forced to pound stakes into the ground so they could find their way home.

The Tres Amigas SuperStation is underground, buried beneath the Llano. It’s made of what’s been described as “up to twenty miles of gigawatt-scale superconductor DC cables, creating a triangular pathway.” The Super Station will connect America’s three major power grids that are known as the Western Interconnection, the Eastern Interconnection, and the Texas Interconnection.

When it broke ground in 2009, then Governor Bill Richardson made it clear that the Tres Amigas project would allow for the uninterrupted transmission of renewable energy from New Mexico, and other sources, into the three power grids and on to the major cities in the nation.

As I understand it, the Tres Amigas will mix renewable energy sources in with other sources of power so that the intermittency of wind and solar energy, a frequent objection to developing them, will no longer be an issue. Calling it “a renewable energy market hub,” Richardson said, when he announced Tres Amigas, that “New Mexico leads the way in green and renewable energy. But we need the ability to send energy produced in New Mexico to surrounding states. Tres Amigas will break that barrier, creating a larger market for our energy.”

An article from the Western Regional Partnership (WRP) describes the Tres Amigas triangle a pathway “similar to highway rotaries that are used to control traffic flow. In the case of Tres Amigas, multiple power transmissions lines will carry power from each of the three national power grids into and out of the Tres Amigas Super Station, allowing balancing of power between the three different grids” and helping to “ensure the smooth uninterrupted flow of power from multiple generation sources in all three power grids to customers across a wide area of the US, Canada, and Mexico.”

The $1 billion project was conceived by New Mexican Phil Harris, the former CEO of PJM Interconnection. PJM is a regional transmission organization in the Eastern Interconnection grid headquartered in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania and serving some 60 million customers. Harris said that the Tres Amigas project was “agnostic,” that is, a device that doesn’t judge where the power comes from. It mixes up power from various sources and transmits it around the country.

Of course oil and natural gas producers, and power companies committed to coal and natural gas, don’t really like the idea of a transmission system which makes irrelevant their major PR objections to green or renewable energy, its unreliability. When the wind isn’t blowing and when the sun isn’t shining, the argument goes, no power is being produced. But when you mix the actual energy produced by renewables in with the constant smooth flow of a grid, the condition under which it was produced doesn’t matter one single bit.

To me, Tres Amigas is the most exciting development in electricity transmission I’ve heard of. It has the potential to be the key that unlocks the national grid from the chains of the oil and gas lobby and makes practical and useful room for other sources of energy. It’s a first step in allowing the United States to seriously cut its greenhouse gas emissions by giving alternative energy a level transmission playing field on which to compete.

Tres Amigas signed its first customer last week, Broadview Energy, a wind energy farm south of Grady, New Mexico. It’s promised to deliver wind power to California for the next 25 years. That’s a small but good way to jump start the future, a future long stalled by the monopolistic powers of the fossil fuel industry and the generating companies like PNM which depend on their energy.

February 09, 2014