Watering Down the Kirtland Jet Fuel Spill

The old slogan used to go “the solution to pollution is dilution.” This, of course, proves to be a tragic lie. Many times contamination of air and water and soil involves chemicals so dangerous that even a trace of them is potentially fatal, and if not fatal then severely damaging to healthy well being. I think the same is true of the dissemination of information about imminent public dangers. Diluting the potential danger with hollow reassurances is far more dangerous than riling up public opinion to take a very serious issue very seriously.

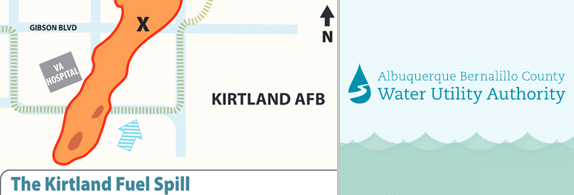

The Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority (ABCWUA) produced an insert in the Sunday Journal last week on the Kirtland Air Force base jet fuel spill that had all the look of an authoritative account of what many think, myself included, is Albuquerque’s greatest environmental disaster. And we have had our share of bad ones.

The insert featured excellent maps and graphics. It acknowledged there is a bad problem. But despite all good intentions it seemed to be written to calm people down, not fire them up.

It had a tone of “there, there, it’s all going to be fine” rather than the kind of sharp call to action that the situation so obviously deserves. Albuquerque’s leadership needs to get overwhelming citizen support to call for a hugely increased effort to clean up the jet fuel in our water. It needs informed citizens committed to winning what could be a long, drawn out struggle over many decades to find the will, the massive amounts of money, and the technology to clean 24 million gallons of jet fuel out of what used to be the sweet spot of our aquifer. This is not a time for distributing rose-colored glasses. And yet the insert put the issue to the Journal’s readers in the rosiest possible picture of what could become a true nightmare in a potentially water-starved city.

The insert states “The fuel spill is located in an important part of Albuquerque’s groundwater aquifer. If left unaddressed it will threaten a critical drinking water well field northeast of the base. As a major stakeholder in the outcome of clean up operations…(the ABCWUA) is working with both the Air Force and NMED (New Mexico Environment Department) to ensure that the spill is not allowed to contaminate any of its drinking water wells.”

In an earlier paragraph, the insert describes the extent of the jet fuel pollution: “We now know that the contamination extends beyond the boundaries of the (Kirtland Air Force) base in a plume of dissolved and non-dissolved jet fuel constituents some 6,500 feet in length and 1, 500 feet in width. The latest official estimate of the quantity of fuel involved is more than 6 million gallons.”

I’m sort of baffled by that paragraph. The most reputable estimate of the amount of jet fuel leaked into the environment, and the one used most frequently, is 24 million gallons, not 6 million , which is 18 million gallons short! The 24 million estimate is one offered in 2012 by an official of the NMED. Why not at least say the amount of fuel involved ranges in estimates of 6 million to 24 million?

And why say “that if left unaddressed it will threaten” the well field when it is threatening it right now?

Dave McCoy of Citizen Action New Mexico, an Albuquerque environmental NGO with no turf to protect and no bureaucratic careers to shield, says correctly that “most people are unaware of the grave danger the 24,000,000 gallon Kirtland jet fuel spill presents to the community’s health and economic prosperity. The danger is being downplayed by the Air Force and the New Mexico Environment Department in their public presentations.” And I’m sorry to say the ABCWUA’s insert didn’t help that much.

McCoy goes on to write that “the size of the plume of Ethylene Dibromide and its extreme toxicity is minimized. The potential for increasing widespread contamination of the aquifer and the municipal supply wells is being downplayed.”

He concludes that “it is only public awareness and pressure that can bring about clean up” of the “plume of Ethylene Dibromide (EDB) that is less than 3,000 ft. from and expanding toward Albuquerque’s Ridgecrest municipal wells.”

It must be said that the ABCWUA does not, and cannot, speak with a single voice. Its governing board is made up of three Albuquerque City Councilors, three Bernalillo County Commissioners, and the Mayor of Albuquerque. One City Councilor, Rey Garduño, has aptly characterized the spill as a “traveling tsunami,” saying “we're pretty soon going to be swimming in this stuff."

The insert, however, reads as if it were cooked up by Mayor Berry, Governor Martinez and their PR Svengalis.

The insert could have addressed the nature of the clean up technology, a realistic timeline for cleanup and the estimated price tag for doing the job. It should have told us if this water will ever be drinkable again, and how much of the water around the plume will be rendered unusable. It might have also addressed the costs of waste disposal and the locations involved. The insert did alert us to the fact that the ABCWUA in 2014 declared that it would “not allow EDB contaminated water at any detectable level to enter the potable drinking water system.” It didn’t say how it would manage that. But in the same sentence it urged “Kirkland and the Air Force to start aggressive clean up immediately.” I would contend that promising to start in the middle of this year, as the KAFB has, is not “immediately.” And that its plan is not anywhere near “aggressive” enough to finish the job in the lifetime of someone born this year.

The insert also never mentioned the probability that the “clean up” would never bring the contaminated water, the actual amount or location of which we still do not know, to its “pure” state before contamination.

But Albuquerque’s leadership and the Governor would like to dilute the whole matter, soft soaping the issue almost out of existence. Remember in 2013 the flack that Congresswoman Michelle Lujan Grisham took when she said the KAFB jet fuel spill and its cleanup should be the number one priority of the NM Congressional delegation? She was accused in some editorial circles of being an alarmist when, of course, she was absolutely right.

Flogged Blogger Raif Badawi

Right in the middle of editorial and political repercussions of the terrorist killings of 12 persons in the offices of the Parisian satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo, and the wounding of 11 others, I found myself watching a YouTube video taken with a cell phone camera in the back of a crowd of onlookers witnessing the flogging of Saudi blogger Raif Badawi. It was horrifying.

Badawi was sentenced to ten years in jail, a massive fine, and 1,000 lashes, 50 lashes at a time over 20 weeks. His crime was writing and hosting a now closed blog called The Saudi Free Liberals Forum, which criticized Saudi clerics and supported, as far as non-Arab speakers can tell, respectful secularism and free speech.

Badawi was in shackles and wearing a white shirt and pants. I think he was handcuffed to a pole that was in a public square outside a mosque in the city of Jeddah in early January. He was surrounded by uniformed officers. One of them, the “executioner,” struck him with a cane very rapidly, but severely, 50 times all across his back. Badawi didn’t make a sound. But he almost had to be carried away.

He would have been beaten with a cane 50 more times the next week and for 18 weeks thereafter, but Saudi King Abdullah intervened and sent the case to the Saudi Supreme Court for evaluation, presumably in response to massive international condemnation. Saudi physicians said Badawi’s wounds from the previous beating were not healing. Imagine having to go through that 20 times, each 50 strokes of the cane laid on top of the previous weeks’ beatings. The pain would be unendurable.

Raif Badawi is 31 and the father of three daughters. His wife and children have fled to Canada. He is a truly brave man. I’m sure he knew exactly what risks he was taking for doing what many of us in this country do with regularity, consciences unstained by anxiety.

Watching the secret video of Badawi’s flogging I saw again the personal nature of terrorism. In this case it was state terrorism. Terror is about individual human beings who are killed or made to suffer terribly by people who think their own politics or religion, or their own power and strategic aims are more valuable than a human life.

This is true for all terror and all terrorists, be it individual fanatics who blow themselves up in marketplaces or fly airliners into buildings, or military strategists who terror bomb cities and fly drones into villages assassinating enemies and the innocent alike, or the rulers of despotic terrorist states who disappear people, torture them, flog them, kill them for dissenting, spy on their populations and mangle those who disagree with them.

Terrorism is really all the same, if you judge it from the consequences. Individual people – with their families, their hopes, their talents, their philosophies and knowledge – are treated not like people, but like obstructing objects to be eradicated or mutilated or terrified so horribly that their fate “sends a message” to everyone else.

Every innocent life, every name that is lost in the grotesque language of euphemisms like “collateral damage,” is an irreplaceable singular human being who has been treated no better than a bug or an ant.

Watching that crisply uniformed Saudi prison guard strike the back of Raif Badawi 50 times made me feel in my own bones that what mattered was Badawi’s life and body and mind and soul. His pain and terror was being used for political and strategic purposes. It was as profane and ugly a deed as one could think of. The dead Paris police officers and the dead Charlie Hebdo cartoonists were used the same way. Every bystander blown up by a drone, a car bomb, a carpet bombing, or disappeared and rendered without equal justice under law, is being sacrificed – wasted to achieve a mere fleeting goal.

This is what Emmanuel Kant meant in the l8th century by the “categorical imperative” of never using a human individual as a means to an end. Exploiting, killing, torturing, terrifying other people is the ultimate immorality no matter what the ends to be achieved-- if you hold that human life is sacred. If you don’t, then you get the flogging grounds of the Saudi’s and the machine gun bullets of the terrorists killing cartoonists for making fun, or the 50 searing blows on a writer’s back.

Raif Badawi. That’s a name and a conscience I won’t forget.

Reies Lopez Tijerina—1926 to 2015

Reies Lopez Tijerina is the only genuinely charismatic historical figure I have ever met, and that includes all the governors and senators and celebrities one runs into in nearly 50 years as a reporter and writer. I first encountered him 48 years ago when I was 26. I interviewed him and observed him many times after that, the last being in l999 when he donated his papers to the University of New Mexico Library with much fanfare and celebration. Tijerina died last week in El Paso at 88, reportedly of ‘natural causes.”

During that last meeting in the Library I introduced myself and shook his hand, which was always like being in the bone-cracking grip of a giant. He recognized me and, with eyebrows raised, pulled me to him and said with some emphasis, “I did not kill Eulogio Salazar. I did not.” I think I said lamely “I never said you did.” But I wondered if he said that to all the old reporters, or if I’d written something long ago that I didn’t remember but that he never forgot. He held onto my hand for what seemed like minutes, then let me go with a grin I knew well. His hair was white in l999, but he didn’t look much different than he had 30 years before – his face vigorously expressive, his whole demeanor bursting with internal energy and focus, full of mischief and humor, and in perfect control of himself and the events around him.

Eulogio Salazar was the jailer at the Rio Arriba County Courthouse in Tierra Amarilla that Tijerina and his followers raided in l967 to make a citizen’s arrest of district attorney Alfonso Sanchez in what has become a fabled and much recounted event in Western American history. When I was in East LA a few years after the raid, super-graphic posters of Tijerina were paired with images of Che Guevara on local café walls.

Eulogio Salazar was murdered in January 1968 after Tijerina had been released on bond facing federal charges from being a part of group that took over the Echo Amphitheater Campground run by the Forest Service at the time. Salazar, who’d been shot in the cheek during the Tierra Amarilla raid, was found dead in his old Chevy off a back road in a clump of trees with his head bashed in and his face beaten to a pulp. To my knowledge no one was ever charged for the killing and Tijerina himself was cleared of any involvement.

Immediately after the courthouse raid, the National Guard was called out to move into northern New Mexico with tanks and infantry lead by a General named John P. Jolly. The next morning in the newsroom of the Albuquerque Tribune I was pulling copy from the international wire with photographs of Israeli forces moving into the Golan Heights, or so I thought. No, they weren’t images of what would turn out to be the Six Day War. They were photographs of northern New Mexico swarming with soldiers and armored vehicles.

Much has been written about Tijerina. Long obits and homages already abound. One of the best books about him is Peter Nabokov’s Tijerina and the Courthouse Raid, published in l969 and still in print. Tijerina’s extensive papers are available at the University of New Mexico Library. My favorite book about him is Michael Jenkinson’s 1968 Tijerina, published by Paisano Press in Albuquerque. It is out of print but available in libraries.

In his introduction, Jenkinson asked “Who is Reies Lopez Tijerina? Among other things, he was a candidate for the office of governor of New Mexico. To dramatize his campaign, he walked one hundred and ten miles” from Albuquerque to Chimayo. “Tijerina is different things to different people – con man, folk prophet, racist, inspired revolutionary….Both the far right and the far left would like to believe him a Marxist. In personal conversation, however, his prime concern seems to be preparations for the second coming of Christ rather than a secular Brave New World.”

Jenkinson got it right when he observed that, “In terms of his audience, Reies is one of the great Communicators of our times.”

I watched his orations many times at the headquarters of his organization, the Alianza, on North Third Street in an old grocery store. Tijerina liked me, thank heavens. I was the Tribune’s “Tijerina man.” I researched the first biography of him in print and followed him through the events of l967. When I went to his speeches not only did I find them spellbinding, but I was relieved that he had appointed one of his brothers to watch out for me as I was the only gringo in the place. And his rhetoric was indeed “fiery” as many described it.

Most of the speeches I heard, and I had enough Spanish then to get the gist of them, were about land grants, land theft, the corruption of society, and mestizaje or the power of mestizo culture and genetic hybrid vigor.

One indelible encounter I had with Tijerina was interviewing him in an empty meat locker in the Alianza headquarters. It was just the two of us in this empty vault. Tijerina was ever on guard against potential assassinations and electronic eavesdropping. He talked for more than an hour mostly about race, and how the races of Europe, Africa, the Middle East and the Orient were all genetically stagnant, at a dead end. And that the only genetic powerhouse left on the planet was Latin America with its mestizo vigor.

I’d never heard anything like it. Tijerina spoke with enormous energy even one-on-one, gesturing, grimacing, laughing, and drilling points home with his forefinger. But after he was through he forbad me to write of what he’d said, if I hoped to get more stories from him for the Tribune.

At the 1999 presentation of his papers, which had been stored underground for years in northern New Mexico, Tijerina was spoken of not so much as a mythological and charismatic figure, but rather as a serious scholar who brought to the light of day, through his researches in Mexican archives, not only the binding agreements of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1842 and their relationship to land grants, but also the many sordid swindles that took land grants out of the ownership of legitimate heirs.

Most of those old land grants were eventually sold by Anglo speculators to the federal government and turned into National Forests. After the courthouse raid not only did Rio Arriba County district judge James Scarborough take to carrying a six shooter in a holster strapped around his waist, but Forest Service personnel were armed to the teeth as well. The land grant movement terrified many. It seemed to some like a “communist” insurrection. You’d hear folks claim that it was all guided from Cuba.

But Jenkinson gave credibility to Tijerina’s scholarship and seriousness, quoting him from a speech made in l957. “The land grants,” he said, “were not dead; they were just frozen. They were living, latent political bodies.” Perhaps what folks really feared was the thaw he promised to bring about and the revelations of embezzlement and foul dealings that haunted and infuriated northern New Mexico for more than a century and still does.

In October of l967, The Alianza held what was to be its first annual political convention at the old round Albuquerque Civic Auditorium. Representatives from Hopi, many northern New Mexico communities, Black Panthers and other groups, and anti-Vietnam war protesters all spoke from the podium. The FBI was taking down license plates in the parking lot as if it were a convention of mobsters at Godfather Don Corleone’s daughter’s wedding. And in the top row of the balcony men in fedoras and double breasted suits huddle around big box tape recorders. As I found out, when I asked, they were agents of Army, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard intelligence, plainclothes men from the State Police, the Albuquerque Police, the Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Department, the FBI and, I believe, even the Secret Service.

Tijerina had gotten people’s attention that’s for sure. And he paid for it with long court battles, and starting in l970, a stint in federal prison for the courthouse raid. The penitentiary left him, many said, a “changed man.”

During one of his many court appearances that I’d covered in the Dennis Chavez Federal Court building in downtown Albuquerque, I had a chance to witness an interaction with Tijerina and another New Mexico legend Emilio Naranjo, thought of by many in those days as the political boss of Rio Arriba County, and a man who had a distinct animosity toward Tijerina. I’d rushed down into the basement after the end of a day in court hoping to get a brief interview with Tijerina. I was waiting at the elevator door when it opened and I saw Tijerina in handcuffs shouting at Naranjo who was a federal marshal at the time. The two shot me dagger looks and stepped back into the elevator, closing the door. I could hear them yelling at each other as I left.

Emilio Naranjo was admired by many in northern New Mexico. He died in February 2008 at 92.

Tijerina was a complex and contradictory man. He was born in Texas, had preached in Arizona, and was loved and admired by some, hated by some, and was fascinating to many. I’ll always consider it a privilege to have known him as best I could. I considered him then, and still do today, to be a savvy, profoundly intelligent, rhetorically gifted man with a passionate loathing of social injustice. Was he effective? Did his theatrics and political actions, and the violence that came with them, serve his cause? Not in the short run, perhaps. But like all mythic figures his influence keeps on reappearing and the injustices he brought to the world’s attention won’t go away either, unremedied as they are.

January 26, 2015