Rep. Lujan Grisham is Right About the KAFB “Spill”

Gasoline, jet and diesel fuel, any kind of refined petroleum products used to power cars and trucks and planes and other weapons of war are poison when ingested. No one in their right minds would drink gasoline, or diluted gasoline, unless as an act of suicide. The fuel itself is dangerous. Most of the additives placed in the fuels during the refining process are dangerous. The vapors are dangerous. There’s nothing about refined petroleum products that should be ingested by living creatures, if they want to keep living.

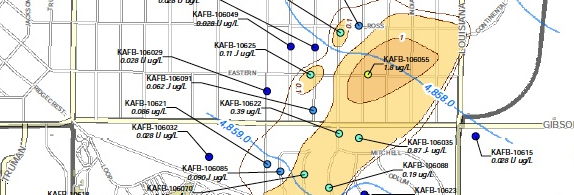

This is why the so-called jet fuel “spill” or “leak” at Kirtland Air Force Base -- perhaps the largest in the nation’s history at 24 million gallons – amounts to an environmental catastrophe for Albuquerque and its groundwater and one that will be plaguing us for many decades, and maybe centuries, at the current rate of clean up.

So when Congresswoman Michelle Lujan Grisham said that getting the jet fuel and its poisons out of our groundwater should be the New Mexico’s congressional delegation’s number one priority she was not “grandstanding” as the Albuquerque Journal accused her of doing in a recent editorial.

Many of us have been wondering for months now why the delegation hasn’t put more pressure on the Air Force and the DOE, DOD, and EPA to appropriate the millions if not billions of dollars it will take to really clean this mess up before it gets into the city’s major well fields near Ridgecrest, if that’s even possible now after all these years of prevarication and postponement.

If one looks around the country at other Air Force Bases it becomes alarmingly clear that the military is not very good at cleaning up contamination that really should never have been allowed to happen in the first place. The former George Air Force Base(GAFB) near Victorville, California, is a chilling example.

Decommissioned in l992, GAFB’s jet fuel contamination is estimated at a mere half a million gallons or slightly more. More than 30 years will be required to pump it out and treat it to EPA safe drinking water standards at a cost, so far, of some $153 million. Parts of GAFB could be redeveloped as a site for a federal prison.

You don’t have to have a scientific calculator to see that 24 million gallons will take a great many more years to clean up and cost astronomically more money. The problem here is that the dangers of the KAFB groundwater pollution have been down played by the Air Force, the State, the City and County, and the morning daily and other mainstream news outlets since the beginning. The actual number of gallons is still an estimate and could prove to be much larger than 24 million gallons.

But the federal government has not appropriated enough money to dig all the many hundreds of new test wells to accurately characterize the pollution plume’s dimensions or speed moving toward the Ridgecrest drinking water wells. We’re still basically flying blind. And the equipment being used to do vapor extraction, according to reports, keeps breaking down. And even after all the vapor has been removed, the poison liquids remain.

The KAFB spill is not in the far reaches of the Mojave Desert like GAFB. It’s in a central section of Albuquerque, near the sweet spot of the Middle Rio Grande aquifer, near where many tens of thousands of people live and own homes. This is not something to be swept under the political rug and downplayed by boosters who don’t want to ruffle Albuquerque’s image.

Of course Congresswoman Grisham isn’t grandstanding when she says KAFB’s pollution should be the New Mexico Congressional Delegation’s number one priority. It is a catastrophe in the making. If everyone wasn’t so blasé about it there’d still be plenty of reason to be upset. But this soft peddling and head patting is intolerable. It’s going to take decades to squeeze out enough money from Congress to do the kind of clean up job that needs to be done. And we need to start now. It’s dishearteningly irresponsible of the Journal to imply that everything is going along as it should when there is more than ample evidence that only thing that’s moving with alacrity is the pollution plume itself, right toward some of our most productive water wells at a rate one estimate has it of 385 feet per year.

The KAFB jet fuel contamination of our aquifer is not an anomaly when it comes to U.S. Air Force Bases. There are at least 39 other known contamination events at bases around the nation and perhaps many more. Known contamination sites include Tinker AFB in Oklahoma, McClellan AFB in California, McChord AFB in Washington state, Griffiss AFB in New York, Wright-Patterson AFB in Ohio, Edwards AFB in California, Hickam AFB in Hawaii, Lowery AFB in Colorado, Luck AFB in Arizona, Langley AFB in Virginia, Mountain Home AFB in Idaho, Pope AFB in North Carolina, Peace AFB in New Hampshire, Travis AFB and Vandenburg AFB in California, and Chanute AFB in Illinois.

As UNM historian David Correia wrote recently in an authoritative piece on the KAFB “leak” in the Weekly Alibi called “The Environmental Disaster You’ve Never Heard Of,” this plume of poison “is the largest toxic contamination of an aquifer in US History, and it could be twice the size of the Exxon Valdez disaster.”

Correia goes on to document the potentially deadly impact of one of the chief additives to jet fuel that was banned more than 40 years ago, but not long ago enough to preclude it being in the jet fuel that started seeping into our groundwater more than 65 years ago. The chemical is called ethylene dibromide or EDB. The EPA has determined that there is no safe level for this chemical in drinking water. It’s zero, period. Current estimates of EDB in the Kirland plume are at almost a quarter of a million parts per trillion gallons of water. That 240,000 parts per trillion vs. zero.

I guess the Journal thinks it’s OK to tempt fate. I’m grateful Congresswoman Grisham does not.

UNM’s President Frank and the Knowledge Economy

When UNM President Robert Frank, in a recent Journal op-ed piece, wrote about universities being “economic engines” that drive innovation in state economies, a part of me felt a jolt of optimism over UNM’s revived interest in playing a real world role in the life of our state.

Another part of me, though, wondered about the trade-offs involved in fueling such an economic engine. Would traditional instruction suffer from a decreased focus? Would the humanities take an even farther back seat to the sciences and engineering in the university’s role as a market stimulator and generator of public/private partnerships grounded largely in publically funded research? Would the university engage in helping to solve local resource management issues, planning and urban design conundrums, and neighborhood welfare needs, or would it simply be another magnet attracting corporations looking for weak economies to exploit and settle in?

The major worry, though, has to do with whose values will fuel the university’s economic engine. Will they be the values of mainstream corporate culture? Will they be the values of the military industrial complex? Will the economic engine be driven by the diverse values and perspectives of the entire university community or will the university become a tool for the party politics of economic development?

It would seem to me that for a university to be an economic engine fueled by its own values, a university-wide consensus would have been sought after and reached about the vehicles the university engine would use and the destinations it would seek.

President Frank wrote that “New Mexico is blessed with the best national research labs in America. By linking these labs with our research universities’ ability to bring knowledge from mind to market, we kick into high gear the momentum needed to help business and industry thrive.”

President Frank goes on to quote a 2011 National Governors Association report that calls for “institutions of higher learning” to help “create new, well-paying jobs in the economy and getting our graduates ready for those jobs.” While it’s almost like the governors’ were calling for universities to become trade schools, who can fault universities for wanting to roll up their sleeves and become players in the lives of the citizens they serve?

What troubles me most, though, in President Frank’s op-ed is this sentence:

“At UNM, we will continue our commitment to align our institutional strategies with the public sector’s economic goals and to partner with business and research communities to take ideas from mind to marketplace, create more knowledge-worker jobs for our graduates and build an experienced workforce in New Mexico.”

Does that mean business, politically appointed economic developers, and the national research labs, run by the Department of Energy and serving the needs of the Department of Defense, will be determining the university’s “institutional strategies”?

Will UNM become an arm of the National Chamber of Commerce, its political allies and the military?

These are not frivolous questions. Because President Frank’s op-ed says nothing about what kinds of goals, what kinds of businesses, what kinds of “knowledge worker” jobs it will help create, he seems to be ceding its values to those of the marketplace.

When it comes to matters of form and content, a university is all about content. Business and business driven research, especially that determined by the military industrial complex, is all about efficient form, process, and production which basically any content can fill. Will UNM become deeply involved in nuclear weapons and nuclear energy? Or might it become involved in solar, wind, geothermal energy science and development, for example? Those are question of content. And for a university those questions must be paramount. Will UNM serve business, or will it serve the citizens and students of New Mexico? They are not the same things.

Will the humanities and those disciplines that lead to richer, fuller lives and competence in self-government and the workings of a free society, disciplines that foster questioning, skepticism, curiosity, independence, flexibility and a heightened social conscience be short changed because they are not geared to generating ideas for the marketplace?

Just what kinds of businesses and jobs will UNM aid and abet? In a state as diverse and intellectually rich and politically volatile as ours, that’s a question UNM has to answer if it is to gain the support of many of even its most ardent alumni and backers. I think UNM could damage itself, and its fund raising efforts, irreparably if it became known as a predominantly business oriented arm of the military, for instance, or if it associated itself with supporting weapons systems and military spy devices, or if seemed to be drifting to an alignment with a political party of the far-right.

President Frank’s op-ed could signal a defining moment for UNM. What kinds of jobs and businesses will UNM support and what kinds of jobs and business will it shun? Or will it abdicate its responsibility to support humane values, civil society, peace and plenty in the world, expanded opportunity for personal enrichment and social action, including honorable work, and become an intellectual machine shop for any business that wants to come to our state?

The Architecture of Change: Building a Better World

When Kingsley and Jerilou Hammett founded a monthly magazine in Santa Fe called DESIGNER/builder: A Journal of the Human Environment in the l980s, they wrote about the spirit of community and personal self-empowerment, a spirit that sensed in various ways the coming of the homogenizing economic juggernaut of corporate globalism and the underclass it was creating. Their magazine opposed with vigor and passion the oppression of specialists, the exploitation of the poor by predatory big money and the financial and social banishment of marginalized people.

DESIGNER/builder was an inspiration to many of us. And now many of its most wonderful pieces have been put together in a new book by UNM Press called The Architecture of Change: Building a Better World.

This beautiful volume is, for me, a textbook of hope. I would love to see every student of architecture and planning, and every social worker and health care professional read it cover to cover. The stories told in the book’s 36 chapters are undeniable testaments to the resiliency, the fortitude and the imaginative genius of the human spirit.

DESIGNER/builder publisher and writer Kingsley Hammett died in 2008. His wife Jerilou, editor of the magazine, joined with writer and photographer Maggie Wrigley to create an anthology mostly of pieces by Kingsley, a prolific, insightful, and opened-hearted writer who loved to tell the stories of quiet genius and gentle persistence and ingenuity in the lives of those who created a world for themselves and their communities, often against staggering odds.

As Wrigley and Hammit write in the introduction, “Over a fifteen year period, through the stories we’ve covered in DESIGNER/builder magazine, we have marveled at the power of personal initiative – of people who refused to accept that things couldn’t change, who saw the possibility of making something better and didn’t hesitate….These essays profile architects, designers, artists, activists, and ordinary people who have challenged the status quo and made exemplary contributions to innovative housing, neighborhood revitalization, alternative education, public art, and community empowerment.”

The stories compiled in The Architecture of Change give the reader a picture of not only ingenious adaptations to cruel conditions, but also why the human species has evolved and survived as it has.

I can only touch on a few chapters here, but this is a book that begs to be read. We learn of a “refurbished postal van” in West Oakland, California, that serves as a “People’s Grocery,” driving into neighborhoods often immobilized by poverty. The People’s Grocery was given a boost by two San Francisco architects who did pro bono welding on the van and contributed ideas for efficient design in the interior spaces.

In a chapter called “A School as Big as New York City,” Kingsley Hammett writes that the “guiding principle” of the “City-as–School” project “was a philosophy rather than a specific structure: put students in a situation where they can learn rather than build a place where they can be taught. Under his model the classroom for students can be unlimited, ranging from sowing crops in city gardens to sewing up cadavers in a city morgue.” These studies fuel students’ curiosities and self-confidence in ways that “teaching to the test” never could.

In “Marking the Places that Matter,” Kingsley writes about “recognizing and documenting…unsung sites as the focus of an organization called Place Matters. It grew out of a task force within the Municipal Art Society working in conjunction with City Lore: The Center for Urban Folk Culture. Place Matters is the first program to solicit and take seriously the opinions of ordinary New Yorkers about places in the physical landscape that they consider to have historic and cultural value. It is broad-based in its approach, its work encompasses places of interest to all classes and ethnic groups and it does not prejudge what should be considered significant.”

There must be thousands of places that matter in New Mexico, places excluded from tourist iconography. No time like the present to start looking for them.

Our aging population, and its evolving needs, is the object of the creative insight of Elaine Ostroff, a pioneer in what’s known as “universal design” and “user-friendly environments.” In “The Evolution of Universal Design,” Kingsley writes about older people who “want to spend their final years in their own homes and neighborhoods and take part in community life.” Builders, he says, “will find it good for business to stop building homes that become obsolete. But the central issue isn’t just about a growing market for the aging. It’s about equity and inclusion. Design has the power to enable people or disable them, to include them or exclude them.”

The Architecture of Change has other fine essays by Katherine Melcher, Jerilou and Kingsley, Maggie Wrigley, Lily Yeh, Dominic Moulden, and Jane Golden.

For people whose social conscience has been disappointed by the progress of the present moment, this is a book that will inspire you to think afresh about the roles people can play in the betterment of their own lives and those of their communities, roles that come to life by activating the inherent gifts that enrich most of us, if we use them – the gifts of curiosity, imagination, and the will to prevail.

January 13, 2014