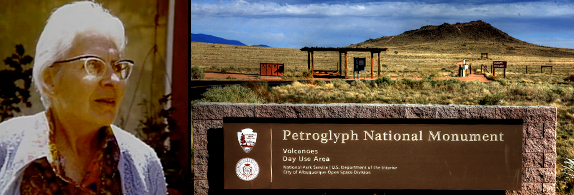

Ruth Eisenberg, The Volcano Lady

All cities, everywhere, owe debts of gratitude to unsung heroes, people who were, perhaps, somewhat known in their day, but are now lost in history. These are the generous souls who established museums, set up soup kitchens, launched chamber orchestras, or volunteer for myriad other good works.

There are many such people in Albuquerque’s past. Among the folks who I admire the most is the late Ruth Eisenberg, who called herself “a little old lady in tennis shoes” and who was called by many allies and adversaries The Volcano Lady. Ruth played a major role in the l970s in envisioning and fighting for “open space” in Albuquerque, a city not friendly to people who opposed building on empty land, any open land, wherever it might be. Back then Albuquerque was so hostile to the idea of empty spaces within its boundaries and beyond that it gave building licenses to almost any kind of developer. Growth as sprawl and sprawl at any cost were the city’s unwritten mottos. And then Ruth Eisenberg came along.

The wife of a retired pediatrician, Ruth decided to go back to school and get a degree in Architecture and Planning at UNM. She was struggling to find a topic for her thesis when she glanced up at the West Mesa Volcanoes and wondered if there was any way to keep them pristine and clear of development. Her professors were eager for her to pursue the topic. Little did they know what they had unleashed on the development world.

Almost as soon as she started looking she found a growing, if marginalized, community of people who wanted to preserve the beauty of Albuquerque’s open spaces – in the Bosque, the Sandia foothills, and the volcanoes. They catalyzed her and she catalyzed them. In the early l970s they created an organization called Save the Volcanoes and went at it with a will.

I wrote in my book, The Orphaned Land, that Ruth was “meticulously organized, charismatic, and relentless, the leader of a team of activists, largely women, who saw that they could enlist a farseeing city council majority with strong representation from the University of New Mexico faculty. The volcanoes define the western skyline of the city and sit squarely in the middle of the most sprawling development in the region – and they remain untouched” to this day. The city preserved the Volcanoes in the mid l970s, spending millions of dollars to buy them outright. It was an idea that would have been dismissed out of hand a few years earlier. The same city council approved in l975 a construction moratorium in the Sandia Mountains above a ten-foot grade. Mayor Harry Kinney signed the preservation measures into law, with some of his detractors thinking he did so only because he couldn’t prevail in a veto over-ride.

After the bills were passed the preservation community breathed a sigh of relief and went about lobbying for funds to maximize the protection of the open spaces they’d helped preserve. And Ruth Eisenberg went into semi-retirement. Then at a council meeting a number of years later, an astonishing idea was floated by Mayor Kinney. He and a few members of the council wanted to revise the definition of open space, from no housing to one house every 40 acres. Preservationists were flabbergasted and infuriated. They descended on the council armed with petitions and arguments and even drew Ruth Eisenberg back into the fray.

Ruth was not a tall person, but she was so full of energy and common sense that she fairly glowed with stature and authority. I remember her walking slowly to the podium to address the council. She said, I recall, that she’d been forced to put on her tennis shoes again, and get back into the battle. “It’s never over,” she commented. “We can never rest.” She said developers have jobs and money and are relentless whereas preservationists are volunteers who eventually tire out. Ruth, and the almost unanimously hostile gathering, denounced the Mayor’s idea as preposterous, pointing out that open space was meant to be OPEN, and that one house every 40 acres would amount to a subdivision of houses with lots of land around them. The Mayor’s idea was eventually swept under the rug.

For a lot of us, Ruth Eisenberg became a symbol of successful civic engagement. If we worry that the likes of her are few and far between these days, her spirit would probably remind us that so much of what we love about our city is brought to us by the quiet efforts and sacrifices of volunteers and givers who would never call themselves heroes, but who keep our museums, our musical joys, our poets and actors and sculptors and painters in the forefront of our lives, and who keep people and children who have fallen on hard times alive and well until luck turns their way again. They do heroic work, even though they’d be embarrassed by the title.

Ruth reminds us that seemingly impossible obstacles can be overcome with enough dogged intelligence and deep hope for what we love and what we think is the right thing to do. Many times when I look admiringly at the volcanoes, or the natural emptiness of the mountain slopes, I think of how easy it would have been to let them be packed with houses. But we didn’t do that. And that precedent is there to alert us to the power that regular people have if they give their all and can sustain it.

Urban Policy Agenda for Albuquerque’s Democratic City Council

Even with a popular Republican mayor in Albuquerque who is masterful at sidestepping any issue that is in the least unpleasant or might cause the slightest acknowledgement of radically changing social, economic, and climate conditions in the American West, the new Democratic majority of the City Council could create and promote an urban policy agenda that might help revitalize our stagnating city.

Ken Sanchez, Isaac Benton, Klarissa Pena, Rey Garduño, and Diane Gibson have been given a golden opportunity to move Albuquerque in the right direction. Good people all, they’ve probably already come in for skeptical cynicism from some in our community who’ve written them off as just another pack of do-nothing Democrats, too timid and disorganized to challenge a Republican with good numbers. This is not a time for the loyal opposition to buy into talk of landslides and mandates for Mayor Berry’s absent agenda. But perhaps we’ll all be surprised. Perhaps these five Democratic councilors will prove the cynics wrong. After all, councilor Isaac Benton also won by a landslide too, in District two.

I’d like to see, at the very least, six policy initiatives started up next year by the Democratic majority of the Council.

First, start to build plans, in public, to move the Albuquerque Police Department away from its current defensive, aggressive paramilitary model to an emphasis on a cooperative, old fashioned, community service, cop-on- the-beat view of policing. This doesn’t mean that officers would be any more vulnerable than they are already; they’d still have their guns and their backups and the choppers and vast firepower. What it would mean, though, is that officers would have a physical human presence in our neighborhoods. People would get to know them. They’d get to know the problems of their areas. An atmosphere of trust and care might have a chance to blossom. It would also mean retraining police officers to deal with the public, to be congenial, helpful, present and full of useful knowledge.

I met a living example of that kind of policing a few months back. We needed help to see if a neighbor was in trouble and called the police. An officer appeared, crisp, courteous, and sympathetic to our problem. She knew what to do. She solved our problem. She made me feel good about APD again. We need more of her kind of cop. Cops on the beat have to get out of their squad cars, untint their windshields and side windows, stop playing Batman and take care of the public’s business. Cops on the beat would necessitate a revised curriculum at the police academy and a new command structure. Many of us would like to know the cop on our streets and even, perhaps, give them some moral support. It’s frightening living in a city with a police department that seems and often acts like Robocops.

Second, start to revise the water rate structure to incentivize serious conservation that would have city residents down to well under 100 gallons a day per capita, rather than the mid-130s, in the next decade or so. While urban analysts in the West worry that population growth will outstrip conservation efforts in most cities, folks have to come terms with the old myth of the “inevitability of growth.” It just ain’t so. If you disincentivize growth, rather than race around after it, water conservation could stand a good chance in the struggle for sustainability. What can’t be sustained is an endless population explosion. Cities like Albuquerque have to stop pushing constant expansion and employ, instead, a high water price to let everyone know there’s not enough to go around in the future without severe cutbacks.

Third, pass a City Council resolution calling upon U.S. Senators Tom Udall and Martin Heinrich to convene public hearings in Albuquerque on the 24 million gallon Kirtland Air Force Base jet fuel spill, the largest by far, many say, of any in the nation. The Senators need to take public testimony from the DOE, the Air Force, Kirtland leadership, the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Authority, the state Environment Department and various contractors at the public trough and tell the whole, true story of this spill, including how little we know about it, how little is being spent to clean it up, how deeply in the dark the public is being kept about its dangers and the cleanup technology being used. Some estimates have the clean- up taking 84 years, or some say 240 years, some say, blithely, 10 years. And no one has said clearly if that part of the aquifer will be potable again. It is, in my judgment, grossly irresponsible to let this issue muddle along out of the public eye. We need the stature of Udall and Heinrich to bring it into focus and to explain to us why a 24 million gallon jet fuel spill hasn’t already become a fully financed and heavily scrutinized Superfund site.

Fourth, start a full assault on poverty, homelessness and hunger in Albuquerque. Start to sell a $15 an hour minimum wage. Argue for a surcharge or add-on gross receipts tax or property tax to build an anti-hunger, anti-homelessness endowment in Albuquerque with the necessary infrastructure and livable-wage jobs to make it work. Albuquerque needs to become a place where no one has to go hungry or homeless, especially a child.

Fifth, begin the analysis, planning and lobbying to shift Albuquerque’s economic goals in a different direction from old, dead-in-the water, corporate incentive-based, land speculation driven, sprawl economy and turn Albuquerque into the home of a vibrant New Mexico “research triangle” focusing on renewable energy development, water conservation strategies, and low-water, high-yield agriculture. Start thinking about making Albuquerque into a mecca for alternative energy and water conservation scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs. Stop incentivizing economic strategies that don’t work, that feed corporate profits but not the local economy, that make Albuquerque seem just like any other place instead of a powerful R and D center that sees the drastic changes ahead as an opportunity for vigor and new vitality in our city and nation.

And sixth, reconceptualize Albuquerque’s cultural assets to change Albuquerque’s image from a nowhere place, a disappointing big city, into what it really is at heart, a town that has worked cultural miracles with very little public expense and has preserved the marvels of its natural setting against all odds in a growth mad city. Help transform Albuquerque from an artistically balkanized place, with its various art forms and practitioners having little to do with one another, into a city with a vibrant synergy among the arts, a synergy that is further energized by the inspiring landscape in which all New Mexicans and Albuquerqueans live.

It’s not like there isn’t a constituency to support a City Council that would actually do something bold and original that helped people, honored our talents, and gave us a fighting chance to survive the brave new world ahead. A Democratic City Council who challenged the stagnant status quo with new ideas would not be booed off the stage. Yes, there would be catcalls from the dead right, but why should anyone really care about that?

Los Alamos and Sandia National Laboratories and Sovereign Immunity

With all its industrial and nuclear waste, and its well documented history of flagrant pollution of public and private lands and commons including dumping radioactive debris into canyons and arroyos, why aren’t Sandia National Laboratories(SNL) and Los Alamos National Laboratories(LANL) designated as Superfund sites. They are surely among the most polluted places in the state.

That’s what Nicole Perez, a journalist and writer recently asked in a UNM Honors College seminar of mine called Environmental Justice in New Mexico. Why weren’t they, and all the other Department of Energy (DOE) and Department of Defense (DOD) nuclear facilities around the country, immediately designated as Superfund sites when the enabling legislation, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) of l980, was passed? It wasn’t because they had handled their waste responsibly, that’s for sure. Part of the answer has to do with CERCLA’S “sovereign immunity waiver.” DOD and DOE have long contended that they are shielded by the immunity of the federal government from CERCLA actions.

New Mexico has lived with LANL and SNL hazardous waste because “waivers of sovereign immunity are strictly construed by Courts, and ambiguities are resolved in favor of the sovereign,” a Library of Congress report from this year states.

Sovereign immunity prevails even though “CERCLA requires that Federal agencies be subject to, and comply with, CERCLA in the same manner and to the same extent, both procedurally and substantively, as any nongovernmental entity.” Not only that, but CERCLA “specifies that State laws concerning the removal and remedial action including State laws regarding enforcement, shall apply to removal and remedial action at facilities owned or operated by a department agency or instrumentality of the United States.” Nevertheless, sovereign immunity prevails.

But State governments do have power. Both LANL and SNL’s handing of hazardous waste was deemed an “imminent and substantial endangerment to health and the environment” by the Richardson Administration’s Environment Department in the early years of this century. Both LANL and SNL were outraged at the accusation. SNL filed a lawsuit in 2002 which held that the State of New Mexico could not, Nicole Perez reports in her final paper, “regulate nuclear waste because that waste is regulated” by the DOE, which is “a co-owner of the labs. So the lawsuit suggests that the DOE is perfectly capable of self-regulation with little oversight, and definitely no oversight from the state.”

While SNL did sign a Compliance Order on Consent with the state, as did LANL separately, it is “clear that Sandia came out on top” in the lawsuit, Perez writes. The Compliance order “forces SNL to clean up illegal dump sites that contain hazardous waste. But the 93 page order doesn’t regulate any activities regarding nuclear waste.” That’s only the in the purview of the DOE. Perez quotes a NM government attorney who was involved with the case in 2004 as saying “It’s kind of like having a fox in the henhouse.”

This episode is one more reason to debunk the notion that voting in local elections, much less national ones, are of no importance. If the Richardson administration hadn’t forced the issue, LANL and SNL hazardous waste practices would be even more deeply hidden than they are.

But now even SNL, itself, is reporting independently its removal of nuclear waste from wherever it was stored in the lab’s precinct. SNL shipped some 131,445 pounds of radioactive waste, or 65,725 tons, off site since 2010, Perez reports.

We’re glad they’ve done it, but it means that almost 66 tons of nuclear waste was stored, or dumped, near the airport and what’s now Mesa Del Sol for decades. And we don’t know where offsite the nuclear waste went, or what kind it actually was.

None of this inspires much confidence given SNL’s history with what’s known as the Mixed Waste Landfill, described by Humberto Lopez as a “Cold War Dump” of 2.6 acres on SNL property. Lopez, a graduate architecture student at UNM and a student in a New Mexico environmental history seminar of mine, has become a serious advocate of removing the dump. Lopez, along with many others including the watchdog group Citizen Action, founded by Sue Dayton in the l990s, and currently under the directorship of attorney Dave McCoy, has been working to get the Mixed Waste Landfill emptied of its contents and moved out.

In the past SLN argued that the dump was too dangerous to move, but not too dangerous to stay put, overlooking the Mesa del Sol. The story went that even though the Mixed Waste Landfill was too dangerous to move, its exact contents were unknown. Although as Lopez writes there are “reports of a document purge in which most of the data was destroyed.” Unknown or classified, some of the waste in the landfill has been documented, Lopez discovered, including 40,000 pounds of depleted uranium, more than a hundred barrels of plutonium, and many tons of other toxic metals.

The Mixed Waste Landfill was capped with three feet of dirt, apparently to keep out burrowing rodents, for what it’s worth.

If this is what “sovereign immunity” is all about, then the courts that undermined the Superfund act of l980, by basically exempting federal military installations from environmental oversight by the EPA and the Justice Department, have done every community in America with a DOE nuclear site, including Albuquerque, a terrible and perhaps life threatening disservice.

December 16, 2013