Stopping Fracking Around Chaco Canyon

Even though we knew about a number of major Pueblo victories that stopped the exploitation and appropriation of their lands in recent years, the thought of fracking for natural gas around the Pueblo ancestral site of Chaco Canyon grieved us mightily. So we decided to take a look for ourselves again.

The washboard road into Chaco last week was as perilous and jarring as it ever was. We rattled and jammed our way down it and into the canyon for what seems happily like the thousandth time. La Fajada Butte, where generations of Puebloan star-gazers spent centuries mapping and memorizing the visible cosmos, announced our arrival with its towering presence, giving a metaphor for the moment of transformation when Chaco replaces the modern world with the eternal.

Chaco is always the same for me – it fills me with a joy that is so intense it is indistinguishable from peace. We were there this time with old friends exploring the land around the canyon, scouring the seeming emptiness for evidence of fracking sites, which we didn’t find, and imagining what it would be like if the oil and gas industry persuaded the federal government to give it fracking leases near the canyon.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) keeps offering fossil fuel companies leases on some 10,000 acres of land around Chaco Canyon for oil and gas exploration using hydraulic fracking methods. While plans are on hold for the near future, extraction industries and the BLM have been working for decades to find a way to exploit the land in the vicinity of the National Historic Park which was designated by UNESCO in l987 as a World Heritage Site.

With fracking comes noise, light and visual pollution, unstable ground, and uncountable amounts of water wasted forever. The more wells, the more din, mess, glare, and sadness corrupting the serenity of Chaco’s holy space.

In recent years tribal authorities, including those from Hopi Pueblos, and environmental groups have caused the BLM to table its aggressive drive to help oil and gas companies to frack near the Canyon. But most know it’s a temporary victory.

The Pueblo world is vigilant. It has not forgotten what happened to Acoma Pueblo, coincidentally in l987, when the federal government, spurred on by then New Mexico Senator Pete Domenici, appropriated, or just flat out stole, over a quarter of a million acres of volcanic flows and their surroundings considered by Acoma to be its own land for millennia. It was, of course, turned into the El Malpais National Monument and the El Malpais National Conservation Area.

This blatant land grab was done to benefit the town of Grants after the uranium bust of the l980s left its economy broken and flat. What few people know but the pueblo world remembers, especially Acoma, is that the pueblo’s leadership bitterly opposed the land grab in every venue available to them. Acoma was stonewalled, ignored, and flagrantly disrespected at every turn.

The idea of fracking for oil and gas near Chaco Canyon brings up issues of land exploitation all too familiar to pueblo people.

The Pueblo world has not forgotten either, I’m sure, that Zuni pueblo in 2003 won a major dispute over the huge Arizona Salt River Project electric utility’s petitioning the Department of Interior for a permit to mine coal near Fence Lake and use water from the Atarque Aquifer which feeds the sacred Zuni Salt Lake. Not only did the Arizona company want to mine for coal, it proposed a rail line to deliver it to St Johns, Arizona, crossing the Sanctuary of holy land around Zuni Salt Lake.

Unlike what happened to Acoma in the l980s, this time the New Mexico Congressional delegation – Pete Domenici, Jeff Bingaman, Tom Udall and, Republican Steve Pierce – all wrote a letter to the Department of Interior strongly requesting that it require the Salt River Project to suspend plans for mining operations near Zuni. The Arizona utility eventually dropped its request for a mining permit at Fence Lake.

Zuni Salt Lake is the home of Salt Mother, as Tom Purdom of the National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (NATHPO) has written. The Sanctuary around Salt Lake “is considered another sacred Native American site where warring nations may enter, put down weapons and walk in peace. Salt Mother is the deity of peace.” Zuni was joined in protesting the Fence Lake mine by the Hopi Nation, the Pueblos of Acoma and Laguna, the Ramah Navajo Band and the All Indian Pueblo Council, as well as numerous environmental groups including the Sierra Club.

Zuni had won an earlier battle with the federal government in l990. Zuni contended that dams and reservoirs built by the government caused erosion and “desertification” of their agricultural lands. Many years of dispute ended when the U.S. government “paid retribution to the Zuni tribe, creating the Zuni Land Conservation Act of l990” wrote Jay B. Norton and Jonathan A. Sandor in Arid Lands News Letter.

“As a result of the Act, the Zuni Conservation Project (ZCP) has begun work toward sustainable natural resource development on the reservation. The approach combines local knowledge with scientific study of natural resources to fight desertification and to revitalize agriculture as an economic entity.”

One of the most important victories against exploitation of native lands involved the highly controversial Peabody Coal mining operation on Black Mesa in Arizona, which sits on both Hopi and Navajo tribal lands. The company was using water from the Navajo Aquifer to transport coal in slurry to the Mohave Generating Station in Laughlin, Nevada, which sent electricity to California, Nevada and Central Arizona. With coal normally being transported by rail, it was said that the Black Mesa mine was the last slurry operation in the country. It was a classic case of environmental discrimination, wasting the invaluable water resources of Hopi and the Navajo for the benefit of urban dwellers in the west.

Peabody Coal got away with its slurry technology for as long as it did, it seems to me, because the Hopi and the Navajo are, for most of Americans, out of sight and out of mind.

This would not be the case at Chaco Canyon should the BLM be so foolish as to force the issue and grant oil and gas fracking permits around the National Monument and World Heritage Site. Lawsuits would be filed, politicians would be activated and the eyes of the world would be upon the federal government. This is not so, at the moment, on Mount Taylor where another controversy is raging over the exploitation of native lands and holy spaces. As I’ve written before in the Mercury, the Roca Honda uranium mine, still in the permitting process with the Forest Service, could damage shrines, medicinal plants, and sacred territory revered by both the Pueblo and the Navajo peoples. What makes it more galling than ever is that Canadian and Japanese companies would profit from the mine at the expense of local people who have a long history of health hazards from tailings left behind from uranium booms in the past.

A victory for Pueblos and the rest of the world at Chaco Canyon would involve the creation of a 10 to 20 mile wide no-drill zone, or Green Zone, around the canyon. Such an idea would surely infuriate oil and gas companies and they would probably sue whomever they could. But a no-drill zone is not as preposterous a proposition as it might sound, given the recent success of Pueblo peoples in disputes with the federal government and private companies. We should all rise up and prevent the atrocity of fracking around Chaco Canyon and insist on a permanent no-drill zone to protect the canyon, its mysteries, ancient sites, and holy places in perpetuity.

Photographer Robert Christensen at the Albuquerque Museum

Anyone who travels by car in New Mexico has seen little buildings in small towns that stir the imagination to spin speculations about the kind of people that might live and work in them. And if the buildings seem abandoned, one could create in a flash a whole inner novel of the lives the building might have housed. Such places are stage sets for invisible history, almost like fossils or a rusted out old truck from the ‘40s found out in a field somewhere. You can’t help weaving tales about them.

When you visit the Albuquerque Museum this holiday season and see the head-on portraits of eccentric little buildings that photographer Robert Christensen took, mostly around New Mexico over 40 years from l973 to 2013, your imagination is likely to take off in fascinating directions. Entitled “Vernacular Architecture of New Mexico,” Christensen’s portraits of buildings are as intimate and personal as a “selfie” one might take with a mobile phone held high for a close but comprehensive shot, if one just happened to be a master photographer. But that isn’t to say these photographs are elegant snapshots. They are meticulously composed, beautifully sighted pieces, works of art in every sense of the word. It’s just that they are uncannily personal and inward too. I’m not sure what it is about Christensen’s technique, but the images are so starkly what they are, and at the same time so respectful and revealing, that viewers are given the chance to form an immediate relationship between their curiosities and the buildings’ forms.

The buildings are photographed in small town places all over the state from Dexter, Acme, Loving and La Joya, to Cleveland, Vado, Mora and Vaughn. Christensen, who hails from Belen, is quoted in the museum catalog for the show as saying that “While quite a few of these buildings still stand, as a genus they are fading away, along with the individualism and self-reliance that produced them. Some have been chicly remodeled at the expense of their original allure, and some have just vanished.”

All of the buildings have what might be called humble origins. They’re gas stations, bars, auto shops, sheds, post offices and little homes, called in the catalog “spontaneously designed buildings.”

Among my favorites is a bare, white, elongated building that has the feel of a geometric modernist painting. It’s in Santa Rosa and has a single closed door with a sign on its roof that reads “Cowboy Jim’s.” I’m sure many a tippler and carouser leaned up against those white walls and then fumbled their way inside.

“Louie’s Gas Station” in Cleveland is another favorite with its sprung, wide open, screen door without a screen, its cluttered windows and “closed” sign in the door. This is the kind of place where you might stop to buy a pop and some cigarettes after your old Ford or Nash had just missed a telephone pole because you’d fallen asleep at the wheel.

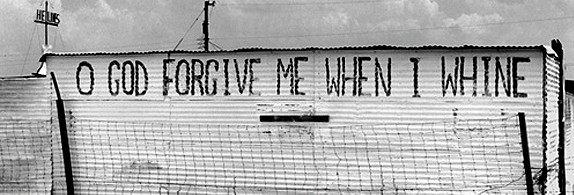

The one that gave me the most pleasure, and caused me to tell many people about it, is a photograph of the back of a corrugated metal building that’s been painted white. On its surface, drawn in large, black letters – without the benefit of a sign painter – are the words “O God Forgive Me When I Whine.” I’d just been looking for a place to sit to rest my knees. When I saw those words I laughed out loud. They struck me as the perfect prayer for this time of my life.

Christensen’s photographs document a world that, like many of the buildings themselves, is in the process of ceasing to exist, a hand-made, hand-to-mouth world of folks with a little grubstake and a will to make it on their own by the side of the road, the world of the very small business that could hold its own in the l940s and l950s, before globalism was anything more than a funny thing to say about a world atlas. The buildings remind me of the places in an Ivan Doig novel, hardworking, proud, thread bare now but not always, tough enough to endure, and designed, if you will, with a sense of personality, whimsy and sure dignity that make the buildings, themselves, representative of the idiosyncrasy and character of those who built them.

Christensen’s photographs of vernacular architecture are at the Albuquerque Museum through March 16, 2014.

Albuquerque’s Fatal Flaw?

It’s become almost passe‘ to say it, but certainly the most disappointing omission of this year’s disappointing mayoral election was the absence of any substantive exchange about water and drought. Candidates said little about it and were asked next to nothing about their views on the subject by the mainstream media. It’s almost as if the guardians of the status quo thought it would be inconvenient if we actually had water problems, or that talking about them would somehow make them worse or lead to mass hysteria.

I wonder if the election of Mayor Berry could prove to be Albuquerque’s fatal flaw. He said the least about water, and won a landslide victory. It’s as if people who worry about our water supply and its quality are thought of as merely old fashioned doom and gloomers by the water establishment and its leaders.

A recent book, The West Without Water: What Past Floods, Droughts, and Other Climatic Clues Tell Us About Tomorrow by B. Lynn Ingram and Frances Malamud-Roam, gives readers a scientific overview of the history of climate turmoil in the West and shows us how the last 100 years have been unnaturally wet, given the geological evidence, and warns us clearly that climate change could well plunge us into more perilous drought and catastrophic floods than ever.

That such realizations are so commonplace around much of the West and such a verboten topic around here, lends an even more curious taint to our silence in Albuquerque. But it isn’t as if the rest of the state wasn’t thinking about water.

Last year at the 57th Annual New Mexico Water Conference, co-hosted by New Mexico State University and U.S. Senator Tom Udall, folks were talking seriously about what might happen if our consumption simply outstripped available water sources. The conference report’s title sums up the problem, ‘Hard Choices: Adapting Policy and Management to Water Scarcity.” Albuquerque seems loathe not only to define hard choices but to start a public discussion about having to make them.

The report’s prologue states that “Although the issues range widely over supply, demand, conservation, technology and policy, a relatively simple reality emerges. It is likely to be drier in New Mexico in the decades to come than it has been in recent decades past….By almost any measure, under current trends and trajectories, future water supply will not meet future water demand in New Mexico. Although supply can clearly be augmented in the future by conservation, improved policy and management, and new technologies, the evidence that emerges from the best New Mexico water science is that significant reduction in demand will be essential to meeting the constraints placed by smaller future supplies.”

The conference stressed the need for increased funding and focus on important research areas that any media hardly covers, including a better understanding of how watershed and forestry management affects water supply, a sharpened effort in regional climate studies to “help predict local impacts of climate change on Southwest water supplies,” and to “encourage” the National Science Foundation to support “research into the potential limits to growth in regions with constrained water resources.”

The report recommends increased support for “smart water technologies” which “reduce leakage from municipal water delivery systems.” The leakage rate on average, the EPA estimates, is “around 14%.” It also stresses the energy costs associated with pumping and treating water and recommends an ever increasing use of solar energy to limit power costs. The report deals extensively with the potential of desalinization saying “at large scales the energy and waste issues associated with desalination remains obstacles in today’s environment, when compared to costs of various efficiency measures in meeting municipal needs.”

While the report supports the “growing trend in water infrastructure” of “reuse of waste water for potable or gray water purposes,” it also encourages research into why reuse is “relatively under-utilized” and why “many aspects of reuse implementation are poorly documented,” including the impact on “receiving aquifers” and “regulations governing quality and quantity of reuse.”

A major part of the report deals with the legal complications and controversies surrounding water transfers from rural to urban uses. But one of its more important proposed actions is to “enhance safeguards for water transfers with irreversible, potentially negative impacts on rural communities, agriculture, and the environment.”

The report also confirmed what many suspect. It said that “arid and developed areas in the United States have higher per capita municipal use rates than similarly situated developed areas elsewhere in the world (such as Israel and Australia.)” The report cautions that “all arid municipalities should improve efficiency in order to prudently prepare for future shortages in times of drought and climate change.”

I wonder what it will take to get Albuquerque to believe it needs to use dramatically less water and adapt to new habits of water use in the long term. I wonder what it will take to get our city to engage in a serious conversation about water, growth and sprawl. Will it ever be possible for the City and County to join with UNM in major water resources management research and economic development spin-offs? Or will we continue to hear merely little drops-in-the-bucket comments from this mayor about using desalinization to augment our water supply, and using the Rio Grande and the Bosque as a theme park?

I hope we won’t have to wait for another election to take climate change seriously in Albuquerque.

November 18, 2013