Water Planning Down the Drain

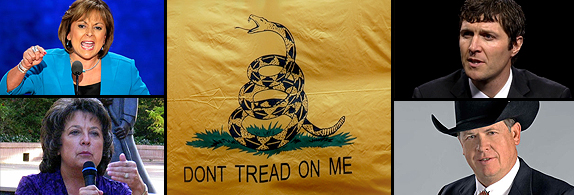

With protracted drought, low snowpack, increased heat and unpredictable monsoon flooding becoming the new normal in New Mexico and around the West, mid-term election voters here chose to return to office what can only be described as an anti-environmental governor and turn the New Mexico House of Representatives over to a climate change denying political party.

Neither Governor Martinez, nor the Republican controlled House, will lift a finger to clean up air, soil, and ground water pollution. And I’m sure neither will become aggressive about perhaps the most urgent issue facing New Mexicans –rational water planning.

Now’s the time for those of us concerned with water to join with many others at the New Mexico Water Dialogue’s (NMWD) annual meeting January 8, 2015 at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. This is a grassroots organization made up of people from all over the state including ranchers, farmers, and urban planners. The topic of this year’s conference is “Planning for a Changed World,” with a subtitle “Learning to Live with Less Water.” They’ll be trying to counteract the vacuum in water leadership that’s stifled long range water planning for at least the last four years.

John Fleck, the Albuquerque Journal’s water writer, will be the keynote speaker. His talk will be on “Sharing Water: What an environmental experiment in Mexico can teach us about social capital, institutional arrangements and the future of water management in the West.”

Without strong groups like the Water Dialogue, the midterm elections could put New Mexico back a decade or more in preparing for what seems to be a steadily growing severe change in our climate circumstances, a change the Republican party and its libertarian allies actually deny is real.

What have we done to ourselves?

Right at the most crucial moment – right when we absolutely must get serious about water and water planning – we basically give our state government over to people who seriously think we shouldn’t do a thing, because they believe there is no problem to deal with. Put that condition together with a U.S. Senate majority going to climate change deniers and government haters, and we see a formula for a the kind of unpreparedness that could end in trouble and misery for many all over the country as well as in New Mexico.

Consuelo Bokum, editor of the NMWD’s newsletter, wrote in the Fall issue this year that “When regional water planning began in the l980s, the average annual precipitation was above the historical average and rising.” But as planning ramped up in the l990s, high precipitation levels were falling. By 2008, when the last regional water plan was finished, a drier trend had set in. And “New Mexico now faces a very different reality than the one faced by water planners in the l980s.”

“It is now likely,” Bokum wrote, “that drought is the new normal, which changes what communities must plan for.” In the final analysis, she said, “there is just less water. The issue is no longer taking steps to reduce demand or increase supply – it will be to learn to live with less and to plan for the social and economic consequences of a changed environment. Planning just got a lot harder.”

But with many political leaders around the state oblivious to the implications of long term drought, water planning is like trying to get water to flow up hill. Cities and towns in New Mexico are still locked into a l960s growth planning model, looking to add to their populations without adding new “wet water” to supply the needs of projected new residents. The Albuquerque metro area, for instance, is projected to grow in population by 7.2 percent over the next five years and reach a total of just around a million people which would be about half the population of the whole state. To reach one million we’d need to add some 92,000 people, come up with the jobs they’d require and the water they’d need to drink.

But getting actual new water, rather than paper water from buying other people’s water rights, is a tough and costly proposition, if it’s even possible at all.

One has to divert rivers, no mean task, like was done with the San Juan-Chama Project at the cost of many millions of dollars. If it rains aquifers might be recharged, but usually at a rate much slower than the use demanded by new populations. There’s always desalination, but we’re way behind in thinking about that in New Mexico. The cost is prohibitive in a poor state and the salt and arsenic waste pose major disposal problems. New “wet water” is next to impossible to come by in a drought. That seems obvious to say, but growth oriented civic groups and politicians still seem to think they can get the water they want for growth without much effort.

That’s why regional water planning – planning for scarcity emphasizing conservation, water rate increases and the costly replacement of leaky infrastructure – is such an uphill battle under even the best of political situations.

What happened to New Mexico November 4 seems like the worst political situation anyone could have dreamed up. Federal money for new water works will dry up with a Republican controlled Congress. Republican leaders in New Mexico will try to proceed with old fashioned population growth strategies because they don’t believe climate change is real and trust the weather will get wet again sooner than later. And while our leaders sit there doing nothing, the old urban/rural split in New Mexico will get nastier than ever as cities blame agriculture for wasting water, and food growers of all kinds accuse cities of growing drastically beyond their water means. And what happens to existing citizens when new residents use more water than a sustainable plan would allow? In the ancient thinking of the l960s, growth trumps everything, including fairness.

And if the flow of the Rio Grande itself is compromised by Texas winning the lawsuit it has brought against New Mexico for pumping too much groundwater in the southern part of the state and slowing the Rio Grande’s delivery of water to Texas, city dwellers from Rio Rancho to Santa Fe and Albuquerque to Las Cruces could find themselves high and dry like most of New Mexico’s ranchers and farmers.

Regional water planning did get a whole lot harder. Without the full commitment of state government it seems next to impossible that anything useful will be decided, much less implemented, in the next four years. It will be left to urban officials around the state to start rationing water usage, a most unpopular, but given the circumstances, a most necessary move.

It Was a Terrible Mistake to Sit This One Out

What else did New Mexicans lose besides any chance for realistic water planning in this midterm election?

We lost the chance to reverse voter suppression tactics coming from the Secretary of State’s office. We most likely lost a dedicated land commissioner to a sagebrush rebel who thinks alternative energy projects and helping sportsmen is “radical environmentalism.” We lost the state House of Representatives to corporatist foot soldiers who see the bottom line as the sole standard of excellence in education, health care and environmental well-being. And we lost a chance to unseat U.S. Representative Steve Pearce, a man from drought stricken southern New Mexico who still thinks human-affected climate change is a hoax.

These situations could give the new Attorney General Hector Balderas and the new State Auditor Tim Keller lots of extra work, In fact many New Mexicans will be looking to these young Democrats, along with the Democratic majority in the New Mexico Senate, to not only help revive the party from its maddening and inscrutable doldrums, but to keep corporate chiselers and would-be privatizers of the commons from ripping off the state at will.

I can see many potential conflicts between Secretary Dianna Duran and Atty. Gen. Balderas stemming from her failure to address malicious voter misinformation campaigns to her focus on single person voter fraud, a condition which virtually does not exist in our state, to various subtle voter suppression tactics involving ID requirements, confusing poll information, difficulties in absentee and early voting procedures, and making voter registration more complicated and difficult than it needs to be.

The governor’s antagonism to environmental regulation, especially of the fossil fuel and mining industries, will probably harden now given her new strengths in the Republican controlled House of Representatives. Her head of the Environment Department, Ryan Flynn, one of those charmers who talks a good game, has virtual carte blanche to precede in any way he wants with deregulating the oil and gas industry, and probably allowing the dairy industry in southern New Mexico the same kind of latitude in polluting ground water that he signed off on with the copper mining industry around Silver City. The Santa Fe Reporter has an excellent piece by Laura Paskus this month on Flynn and the State Environment Department. There’s lots of potential work for Keller and Balderas there.

The new Attorney General and State Auditor could also have their hands full with the virtually autonomous office of the State Land Commissioner. The race between the Sagebrush rebel Aubrey Dunn and the environmental conservationist Ray Powell ended close to a tie with a mandatory recount under way as I write. If the State Land office should change hands and go to a person who’s supported by the oil and gas industry, has said nothing about renewable energy that I can find, and who considers government itself a bother and a distraction, all of us, including the Attorney General and State Auditor, need to pay close attention to what’s going on. State Trust Lands amount to some 135 million acres, and supply education in New Mexico with crucial revenue including some $9 million dollars to UNM last fiscal year.

Dunn accused Powell of being a radical environmentalist. And yet one of the contributing factors to Powell’s defeat, from my perspective, was the inexplicable failure of the influential Conservation Voters of New Mexico to endorse him in this election. And now conservationists might well have the radical anti-environmentalist Aubrey Dunn to deal with until 2018.

Much of what happens at the Land Office used to be clouded in public unknowing. Ray Powell, as he repeatedly said, tried to “let the Sunshine in.” If Powell is defeated in the recount, the Attorney General and State Auditor could serve the public well by keeping an eye on the Republican Land Commissioner who belongs to a political party that likes to run government by private email and is about as transparent as a lead wall.

What a tragedy for alternative energy development and for crucial efforts to reduce greenhouse gases this election has been. And the disaster could spread to union busting with new Right to Work laws, to people who depend on food assistance, to those suffering from mental health issues, to the contamination of Albuquerque’s groundwater with the Kirtland Air Force Base Spill, to public education and its increased vulnerability to privatization in which public money goes to lining the pockets of Republican dominated private corporations out of state.

What a mistake it was for people to sit out this election, and for Democrats to have become crossover voters installing a regime completely antithetical to liberalism’s most fundamental ideals of equality and conservation.

Why We Love New Mexico: Casa San Ysidro and the Minges

Ward Alan Minge was perched on a scaffold high up an adobe wall in the late spring sun, a bucket of mud and straw at his side, putting yet another coat of adobe plaster on the walls of the Sala Grande of Casa San Ysidro, a l9th century rancho in Corrales, that he and his wife, Shirley Jolly Minge, had been restoring since the l950s. I remember the image vividly. It must have been in the early l970s. I’d been friends with the Minges since the late 50s when I arrived in Albuquerque.

The image of Minge, scholar and author, perched on that scaffold, covered in mud, beaming down at me from his labors, was perfectly in keeping with the years upon years of joyous effort it took to restore, and faithfully add to, the rancho in ways that were scrupulously true to historical reality, true to every layer of mud plaster and every layer of adobe brick.

The Minges’ collection of old doors including the l830’s gate for the zaguan that opened on to the plazuelo, their ingenious “cactus wall” of adobe planted with cholla as a security measure, and their collection of religious artifacts such as the Cruz de Animas (Cross of Souls) from Mexico, which was a popular item in homes here in the l9th century, made a visit to the rancho a rare and sought after delight.

Casa San Ysidro is one of those uniquely New Mexican marvels, restored and created by uniquely New Mexican scholars and collectors. Where else would you find a doctor of history and a reserve colonel in the army spending a good part of their lives restoring and adding on to a rancho built originally around 1870 in the fashion of the day, as a building with Greek revival trim and organization?

The rancho originally belonged to the descendants of Don Felipe Gutierrez who was granted the township of Bernalillo in 1704. The Minges had been collecting Spanish colonial artifacts before they bought the rancho in l957and continued to do so for years, using what came to be called Casa San Ysidro as a living museum for their collection and for l9th century Hispanic architecture. They added many adobe rooms, including the Sala Grande, to the original house so it eventually came to surround an interior patio or plazuela.

I was lucky enough to be invited there on several occasions. It was, indeed, like visiting a world long gone. The Minges were sticklers for every detail. And they did most, if not all of the heavy labor and detail work themselves. It was a labor of love that turned into a thrilling achievement of scholarship and hard labor that became a homage to those who lived and farmed in the Middle Rio Grande Valley.

Ward Alan Minge worked for years as a historian involved in Pueblo land and water disputes. His book Acoma: Pueblo in the Sky is a classic of its kind. The stone floor in the Sala Grande, or great hall, and the rancho’s restored private chapel came from paving stones given to Minge by the Acomas. Shirley Minge filled the spaces between the stones with mosaics of shale.

The Museum of Albuquerque acquired Casa San Ysidro in l997. The Minge’s donated the land and the house to the museum. Shirley Minge died at the age of 77 in 2001. As far as I know, Ward Alan Minge, who was born in 1924, lives in Waterville, Kansas.

(Photos: Rio Grande River by City of Albuquerque / CC; Dianna Duran by Steve Terrell / CC; Ryan Flynn from New Mexico In Focus, Episode 730; Gadsden Flag by EmilyRides / CC; Vegas from Casa San Ysidro by Steven Harris / CC; Window from Casa San Ysidro by John W. Schulze / CC)

November 16, 2014