Lucile Adler

When life gets more difficult than usual – when it seems like old friends are dying in droves around you, or when your government is shut down by people who pledge their allegiance to their political party not to the general welfare of their fellow citizens – I think of the life and politics of New Mexican poet Lucile Adler who died close to a decade ago.

Adler used to say, with typical modesty, that she watched the world from her kitchen window. But her passion for kindness and generosity in the face of the world’s horrors gave her the strength of a giant. Her sister spent her life in an iron lung suffering from polio and her husband was a POW in Nazi camps during WWII. She internalized the great tragedies of war in her lifetime, from Korea to Vietnam, from Guatemala to El Salvador, from the Cold War to Mutually Assured Destruction with its nuclear arms race.

And late in life, she contracted a near fatal illness that left her without the ability to navigate normally through her daily life but did not impair her devotion to other people and her disciplined genius as a writer. Though she had a hard time with a grocery list, the poems of her last years were among her finest. The penetrating clarity of those poems along with her never failing thoughtfulness and concern for others gave those who loved her a model of how to live a life of hope and open-heartedness even in the worst of circumstances.

In an introduction to her collected poems, Amulet Songs, I wrote that Lu’s life and work were driven by a “rational optimism” and were, indeed, amulets “against the seductions of despair.” Her inner strength was rooted in the welcoming ethics of her friendship, the outpouring of an unfailingly appreciative maternal spirit directed toward anyone who approached her sphere of awareness, anyone, that is, but those who put egoism and power above the care of others.

Adler lived most of her adult life off upper Canyon Road in Santa Fe. She and her husband moved there in l950 and raised two children. She didn’t publish her first book of poems until l967, though she’d published in The Nation, the New Yorker, and other major magazines. Win Scott wrote of that first book, A Traveling Out and Other Poems, that it was “an exceptionally distinguished first book by a woman who becomes at once one of the really interesting poets in America. The book is filled with intuitive wisdom, a strong feminine objectivity, and I like the way in which it cries ‘Risk Joy’.”

Lu Adler chose a quiet life, one of family and children, of steady writing, of a stoic commitment to opposing oppression of every kind, and of a tireless political concentration on peace and human rights around the world and in New Mexico.

The final poems in Amulet Songs were written in a nursing home when she was unable to care for herself. These are astounding poems, ones that surprised even her. How could her poetic voice have remained intact and evolving? But it undeniably had.

In the final section of Amulet Songs called Age Without Medals, appears this poem entitled “With Certainty and Praise.” It begins, “Here are the hours of defeat/to memorize/and pass along, long days/to tear apart, fold open/and write notes on notes/complaining about all/the losses….Tonight, when all the doors/should stand open and/all the light should/stream through, /and what is learned/erase itself down/to the frayed white page/the long day memorized,/ready to be passed on,/and graded at last, /with certainty and praise…”

This is Lu Adler living life as it actually is, never presuming to judge fate, never denying its agonizing contradictions and confusions, or missing a chance to find something to redeem the miseries, whatever they might be. That is why I’ve always considered Lu Adler the perfect example of what it means to be mature.

In a collection of her prose poems entitled “Letters to the Young”, Lu wrote about the Plain of Jars in north central Laos where numerous bloody battles were fought in the early l970s during the Viet Nam war. “Remember how the wind, rising, used to shake the dry sunflowers under the Russian olive trees? Then we would go in for supper. Now the world is crowded with men like broken pieces of glass, and we have allowed hatred, jagged glances, a brutal reality to pierce us….”

“….trust will come back, if it will, like the new rice in the Plain of Jars, the green harvest, magic grains of rice or wheat that would revive the field where you and the Delgado boys wrestled. (We don’t know this can happen, but it must be planned for, in case, as though – all the way to the world’s end if necessary.)….You have no choice, really, but to try. And remember, as you search emptiness stubbornly for fidelity and love, remember how stubbornly people lean on their simple lists. That is where we begin; it is the least we can dare. You will find your own vivid paths and ways, but remember, even Rimbaud [in his Season in Hell] said at last, ‘Let us never curse life.’”

Meteoritics

Dust from space and little pieces of space rock apparently reach our world all the time, some making it through the atmosphere, some not. The stuff comes from very far away and not so far away. When a big meteor hits the moon or Mars the impact may be strong enough to jar loose small pieces of those space neighbors and send them out into the solar system. Some of them might fall on us.

A meteor at the University of New Mexico’s Meteorite Museum in Northrup Hall looks to geologist like the rock samples Apollo astronauts collected from the moon in the early l970s. And, indeed, it’s a meteor from the moon. You can only see photographs of that lunar meteor now because it’s been locked up for security reasons. Some greedy rock pirate actually stole specimens from the museum not long ago. So I didn’t have a chance to eyeball up close that singular lunar rock.

But even its image has given me a more intimate feeling about old Mr. Moon. It’s like having a memento from a person long gone in your life. Just having that pen or that shirt with perhaps a faint hit of cologne, or that little doily she made when she was ten, just having something of them in the sphere of your present experience keeps you strangely close to them.

It’s the same with the moon now. That moon stones can become meteorites, means to me that the moon is not so far away, not so unapproachable, not beyond my capacity to experience it first hand, or almost first hand, save necessary precautions taken to protect it.

That lunar meteorite also opened me up to a whole other world of falling objects from the sky, a good sampling of which are at the UNM Meteor Museum. And fully on view, if you can find the person with the key.

Meteors have fallen all over New Mexico – from Costilla Peak, Wagon Mound, and Roy in the north to Puerto Ladron, Oro Grande, El Capitan and Picacho in the south.

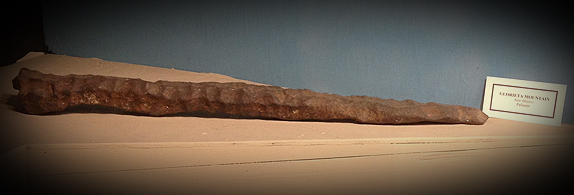

Meteorites, it turns out, come in all shapes and sizes. My favorite at the UNM museum is the walking stick meteor. It’s about the size of my cane, but it appears to be iron, and heavily pocked with what I imagine are tiny craters from many other impacts. How it got to earth without being burned up is hard for me to fathom. But there it is -- like a leprechaun’s shillelagh. It must have plunged through the atmosphere point first. It was found in the Glorietta Mountains on the way out of Santa Fe to Las Vegas.

The museum has a relatively huge meteorite, about the size of one of the boulders that cover the sides of the water reservoir on Redondo Drive near Yale Boulevard. But it isn’t smooth and river tossed. It’s a big hunk of a flaky kind of stone that fell in a field in Kansas a while back. Farmers said it scattered and spread fragments out over the fields, and they just had to plow the pieces under.

Wandering through the Geology and Meteor Museum I couldn’t help but want to physically touch these wonders, get closer to them, make them a deeper part of my experience. I’ve ways thought that “rocks” of all sorts have received a kind of special dispensation from the divine powers to exist solely as objects of beauty and awe. And this week I thought of Helen Keller when she said “Everything has its wonders, even darkness and silence, and I learn, whatever state I may be in, therein to be content.” From the darkness and silence of space come these meteoritic reminders that imagination and curiosity not only lead to experience, but are experiences themselves. And that everything has its wonders.

Miller Moths and Other Plagues

Good people I know speak in desperation from time to time of “overpopulation” as being the world’s greatest problem. Folks around them often nod their heads in agreement. But that’s always as far as it goes.

To solve overpopulation fast means one thing – the death of billions of people. To solve overpopulation as a long term strategy means policing people’s intimate behavior in ways that are inconsistent with a world anyone in their right minds might want to live in.

So, yes, overpopulation is a great problem, but one with no humane or moral or even practical solution, as far as I can see. Except, of course, to bring everyone’s standard of living up to such a decent level, as ecologist Barry Commoner suggested, that infant mortality is no longer a driving force in population expansion. Short of that, nothing’s to be done. We are not insects to be exterminated.

It’s one thing when in a particularly wet spring, for instance, and under exactly the right conditions which can’t be fathomed by mere mortals, millions, if not billions, of miller moths burst into our houses, out of our of cars, from under the trim, swooshing maddeningly into our lives and taking over anything and everything. But they are moths in a mob. Not humans. And like any mob they are dangerous and almost deranging in their fluttering insistence. And you’ll do anything to be rid of them. And that’s appropriate. They are moths.

And then you see one of them, just one say, on the white refrigerator door, or two or three clinging to a screen and you realize they are not only individually beautiful, but that they are each quite different in their markings. You’re confronted then with the paradox of individuality, and how it is obliterated when it exists in the context of the collective existence of a mob.

With moths, one reluctantly must clear them out of one’s life. It goes without saying, I hope, that with human beings individuality and the value of the individual person is never obliterated by mere numbers. An individual human life, breathing and alive in the world, is always paramount. Only despots think otherwise.

It’s not only that we have too many people on this planet. It’s that we have too many people living in misery and torment and conditions of hopelessness and despair. Instead of overpopulation we have to talk about hunger, disease, political oppression, wretched gender bias, corruption, and gross inequality of income and well-being and education.

We haven’t had a miller moth infestation for some years in Albuquerque. The conditions and timing have not been right.

Human overpopulation is tied to conditions as well. The more compassion, education, and equality there is the less human overpopulation becomes a hopeless threat to everyone. We don’t have to kill people off, or hope for a plague. We just have to treat everyone better.

When all people have opportunities for satisfying lives and women have total control of how many children they do and do not have, then at least we’re turning away from an increase in births driven by high rates of infant mortality toward a major decrease in population arising from more optimal conditions for a good life. That’s not a quick fix. But it is a solution.

We Forget the Weather

In January 1971, the temperature at our house in Albuquerque’s North Valley was 18 degrees below zero. It was the coldest freeze on record. It seemed to hover around that temperature for more than 10 days. It was so cold, the pipes in our old house froze solid the first night, the old VW had to have a light bulb on under the hood all night to keep the engine from seizing up, and the cat pushed cold hands away from his hideaway and its electric heating pad. It was a January never to be forgotten.

I wish, though, that I’d kept a better record of it, and of the other odd weather events of the last 40 years or so. But now that The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued a statement last month that affirmed it is “extremely likely” that human activity is major cause of climate change, I’m going to keep closer track of climate change in our own backyard.

This year already we’ve had some powerful and, it seems to me, unique events. Granted, the freeze this January was nothing like the arctic ice cube of l971, nor the ice storm of several years ago in early January. But this year we got down to a very dry 9 degrees. And it stayed very, very dry for months and months. Even the little snow that did fall was dry. And then in early July Santa Rosa found itself covered in two feet of hail and a few weeks later the Middle Rio Grande Valley was subjected to hurricane force winds of up to 90 miles an hour and horizontal rain pelting everything with phenomenal force. Thank heavens that didn’t last more than an hour.

And then last month we see the greatest rainfall in the state since l929 -- day after day of massive storms. They were so powerful and so frequent that even the reservoirs outside of parched Carlsbad in southeast New Mexico– Brantley and Avalon—were close to full or sometimes over-flowing, supplying the area with enough water to ease fears somewhat about next year’s irrigation, but not much beyond that.

What’s ahead for us this winter? Will we get a 2011 snowpack in the Rockies and ease the drought in the western states? Will the Colorado River Basin get the water it needs to prevent serious curtailments of water use around the west? Will we see deep freezes, long lasting ice storms, or some other unique moment in our weather history.

Whatever happens, I’m going to try to keep track of it in my journals, even though I am known in our family to be a little ragged as far as dates are concerned.

But I know this much about 2013 – it was as dry as dry can get, and as wet a monsoon year as any of us have seen. And the wind, a normal plague around here from time to time was for a moment so ferocious it seemed like a cyclone. From my way of thinking, this all substantiates on a local level the patterns of climate change – the same old weather stuff, only wildly more intense. We’ll see.

October 07, 2013