A writer's name appears on the cover of his novel. A painter signs his canvas. A playwright is credited on the program. A star's name adorns a marquee. But what of an architect?

His creation obscures rather than announces him. He lives and works in the shadows of his buildings, which are named for their location, function or owner, not their creator.

However, there are two famous exceptions: the Eiffel Tower in Paris and the Paolo Soleri Amphitheater in Santa Fe.

Soleri, the visionary creator of the graceful but shuttered Santa Fe landmark, died last month in Arizona at the age of 93, having outlived the useful life of the building that is the only one to bear his name.

The boldest venture of this always bold man was called Arcosanti, an 860-acre new city 70 miles north of Phoenix. It was a vision of a new kind of urban life in which humanity and nature coexisted in symbiosis, in a self-sustaining community.

Although he worked on the project for 40 years, it was only 5 percent complete at his death. Designed for 5,000 residents, it had only 90 people living among its 14 primary buildings at the time of his death.

Three years before his death Solerei told the Arizona Republic he would never finish the gargantuan task of building the new city: “I am a a prisoner of my own age.”

Born in Italy in 1919, he came to the United States in 1947 when he won a fellowship to train under Frank Lloyd Wright.

During the 1950s he thought seriously of living in Santa Fe but decided on Arizona because its weather was better for working outside year-round.

Although he designed the Paolo Soleri amphitheater in the 1950s, it took more than a decade to open, and even then it was incomplete.

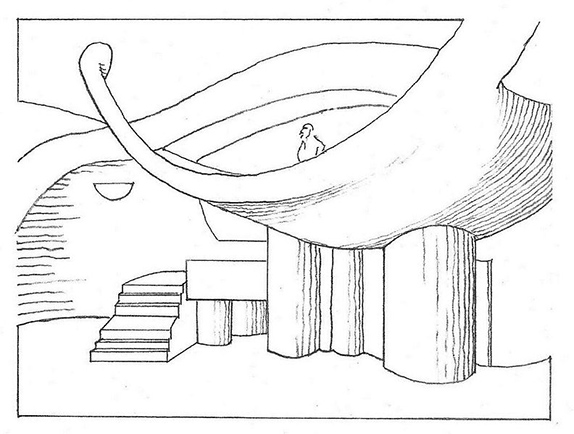

The concrete structure built on the grounds of the Santa Fe Indian School uses an unusual earth-forming technique developed by Soleri to mimic a desert landscape with echoes of Native American motifs. It is shaped like wings emerging from a bowl.

The New York Times described the theater as “an eccentric performance space in Santa Fe whose stage design evokes Salvador Dalí.”

Although expanded from Soleri's original design, it still seated only 650. Nevertheless it hosted such notable performers as Carlos Santana, Leonard Cohen, and Crosby, Stills and Nash. The last performer was Lyle Lovett three years ago.

“In the process of building, the ambitions of the school grew,” Soleri said in a 2007 interview with the Santa Fe New Mexican. “So we started with a relatively modest project, and we carried on the modest project to its conclusion almost, but then they felt that they wanted to enlarge the audience.”

The Santa Fe Indian School announced in 2011 it would raze the building because it could not afford the $100,000 annual cost of maintenance. Soleri wrote, “I am willing to do anything to support preservation of the theater.” Protests stopped demolition, but the theater remains in limbo, unused but still standing.

In the 2001 book, “The Urban Ideal: Conversations with Paolo Soleri,” Soleri, a utopian and urbanist, described cities as the antidote to suburban sprawl and environmental destruction. By concentrating people in dense communities, he explained, we would both provide a better life for people and preserve more of the agricultural and natural environment.

He worked to create a new kind of community that the architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote in The New York Times “held out a promise of not just an alternative architecture but alternative culture.”

His utopian Arizona project has been described as “Buck Rogers meets Buckminster Fuller—a 1960s version of the future set on a vast parcel of highlands amid basalt mesas, juniper and prickly pear cactus and crossed by the Agua Fria River.”

With concrete domes and tall apses, it includes apartments, a bakery, a foundry, a ceramics studio, an amphitheater and a swimming pool.

He invented the word “archology,” a combination of architecture and ecology, to describe this vision of conservation melded with community in a planned urban setting.

One critic called Soleri “a desert Obi-Wan Kenobi,” after the Star Wars character.

An architect who worked with Soleri, Will Bruder, said of him, “Paolo’s mind was always going out into the cosmos. I learned how much you can do with very little, the potential of simplicity and the ability to make unbelievable things from modest means, to dream huge dreams.”

May 14, 2013