Dr. Arthur Rolnick—the keynote speaker at our 2014 NM KIDS COUNT Conference—made a compelling case for higher levels of investment in early childhood care and learning services. Many people in New Mexico agree that these kind of investments will help us improve the well-being of our children. Unfortunately, there has not been a consensus in Santa Fe on how to pay for these programs.

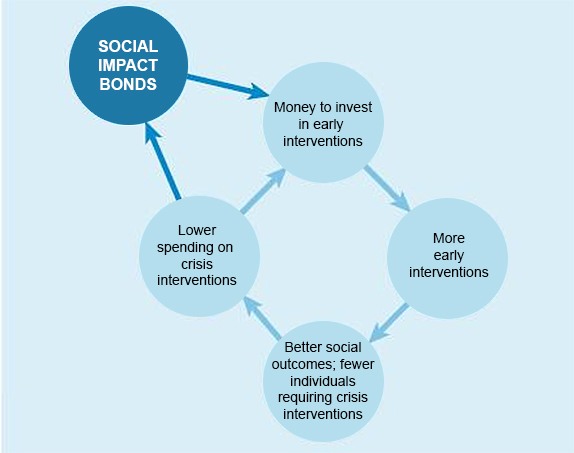

Other states and countries are using a new financing tool—social impact bonds—to pay for preventive high quality early childhood programs like home visitation, childcare and early learning, and pre-K, which have a clear pay-off. The term “social impact bonds” is really a misnomer in that the government does not issue bonds to pay for the programs. Social impact bond financing programs are also referred to as “results-based financing” and “pay-for-success” programs. As these names imply, they are based on the premise that pay is made only when results have been delivered.

So what is results-based financing? Under results-based financing programs, private investors or philanthropists, sometimes jointly, pay for programs that will save taxpayer dollars in the future. In essence, they pay for prevention rather than remediation. Here’s how it works: in the case of early childhood education, non-public dollars are used to pay for high-quality, multi-year programs that are expected to reduce (not necessarily eliminate) the need for expensive special education services and other remediation programs. The investors—private and philanthropic—are then repaid with government dollars, with interest, as the programs demonstrate success in obviating the need for other already-funded programs. Clearly, a critical element of this funding structure is agreement between all parties upon what constitutes success and how that success is measured.

An exciting potential of such financing tools is that they increase the pool of funding for critically needed preventive programs using non-governmental sources. In the U.S., use of this new financing tool has been relatively small in scope and not mature enough to demonstrate whether or not it will be successful. A downside of this financing tool is that the money provided by the private or nonprofit funders must be re-paid with an agreed-upon profit—to cover principal risk and fees—built into the payments, which means that the programs may end up costing more than if they were funded directly by the government. If properly structured, investors are only repaid if the savings are realized, which requires a high level of diligence on the part of government officials.

If such programs prove to be highly successful they may be worth the extra cost. Dr. Rolnick indicated that the return on high-quality early childhood care and learning services has been shown to be 16 percent or higher. It may be worth diverting some of this return to expand these programs with social impact bonds if there seems to be no other way to pay for them. We also need to ensure that we will not end up taking money from other already under-funded programs to re-pay the private investors.

To learn more about social impact bonds go to the Harvard Kennedy School’s Social Impact Bond Technical Assistance Lab at www.hks-siblab.org.

September 15, 2014