Thirty-five years ago I arrived in New Mexico to spend a night camping on my way to San Francisco. Although I have since spent shorter or longer spells in many places, including most recently northern California, I never really left New Mexico after that fine autumn night with stars blazing in crisp mountain air.

I have been remembering of late what life was like for me and for this state when I arrived in the fall of 1978. The end of one year and the beginning of another is the kind of time that forces perspective on a guy whether he wants it or not, to compare past and future, and examine, perhaps with askance, the bridge that is the present, the link between past and future.

A lot has changed in these 35 years. A lot hasn’t.

These two sentences, and the distance between them, are the measure of a life.

I arrived in Santa Fe with little but the memories of past lives I had abandoned, more lives and more abandonment than I now care to remember. What I had in surfeit was the delusion that in leaving behind a place I could also leave behind the person who inhabited that place; and the corollary, that in inhabiting a new place I could become a new person.

The idea of moving on, of building success upon failure, seems inbred in the American psyche. After all, in one way or another, in one decade or century or millennium or another, all of us moved on, moved away from where we were to come here, and did so not because our past lives were such magnificent successes but because of precisely the opposite, because in some way we had failed in our past lives, failed to find sufficient food or health or achievement or pleasure or money or land or family or love or whatever, and hoped we could find it in a new place.

For me, that new place was New Mexico, albeit by happenstance rather than calculation.

The odd, inexplicable thing was that once here I did find something new, and in finding something new, I found someone new, a self that I had not previously known. The closest I can come to an explanation is that I didn’t really change but being in a new place, in a new kind of place, allowed some aspect of myself that had been smothered in the old place, Washington, D.C., to breathe free and fresh and full.

The New Mexico that I found in 1978 was a more open place than it is today, more open both physically due to the smaller, more rural population, and psychologically, due to the state’s isolation from the homogenized national culture and economy.

In those days newspapers and banks were locally owned, and even small towns seemed to have at least one of each. Retail stores and restaurants and hotels were mostly locally owned and managed. When you bought food, you paid a clerk, not a machine. When you cashed a check, you handed it to a teller rather than inserting it in an ATM slot.

Most important of all, when I walked down a street and passed a stranger, he or she would look me in the eye, perhaps nod, maybe even murmur hello or good morning. Such behavior was rare in my most recent homes in Washington and Baltimore and entirely unknown in my earlier home in New York. There, I had discovered that my very survival could depend on avoiding eye contact.

During the late 1970s and early ‘80s my home was is Santa Fe, and what impressed me most about that town at that time was the lack of segregation. Hispanic and Anglo, rich and poor lived next to each other, ate in the same restaurants, drank in the same bars, walked the same streets. At my favorite neighborhood bar on East Canyon Road the joke was that you could tell the rich from the poor because the rich had holes in their jeans while the poor wore new jeans. A lot of old Hispanic families still owned land on the now posh east side, and they still lived in family-owned houses on that land.

The great gentrification of the city was in the future. Santa Fe in those days seemed to be almost a classless society. If you had real money, you didn’t show it off. You lived in a small house made of mud that tried to melt into the earth whenever it rained, just as did those who had next to nothing. If you had a job, you didn’t work very hard; and if you did work hard, you at least pretended you didn’t. On the other hand, if you didn’t have a job, you spent a lot of time working pretty hard to make ends somehow meet. Both classes seemed to behave much alike, in other words.

Albuquerque, then as now, was a different world, but not as different as it has since become. The metro area was a third its present size, and almost everyone lived east of the Rio Grande. It is one of the remarkable things about Albuquerque is that while its population has tripled, it has not become significantly more urban. Rather than taking on the life of a dense urban city, it simply spread out north, south and west.

And even east. The East Mountains and Estancia Valley, once rural areas, have become absorbed into the metro area as suburbs. Most people commute to jobs in the city. Most go to the city for recreation and entertainment. Most do their shopping in the city.

In some ways the good old days were not very good. Communal tensions—between Hispanics and Indians, Anglos and Hispanics, ranchers and hippies, Puebloans and Navajos, city dwellers and rural folk—were high and not infrequently led to violence. Poverty among some groups was extreme. The Legislature, believe it or not, was even more corrupt and disrespected than it is now, and the governor was even more irrelevant to what was really transpiring in what theoretically was his (or her) domain.

I would no longer want to live in the New Mexico of 1978 with all its poverty and injustice and conflict. But when I arrived here then, it seemed a blessed state. Despite all I know of its flaws and foibles today, enough of that euphoria is extant that I don’t know any place else I would rather live.

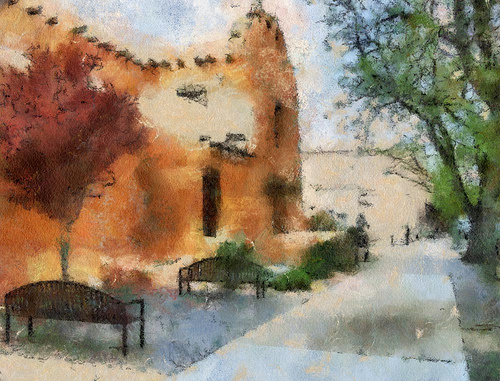

(Image by George Holmes)

January 01, 2014