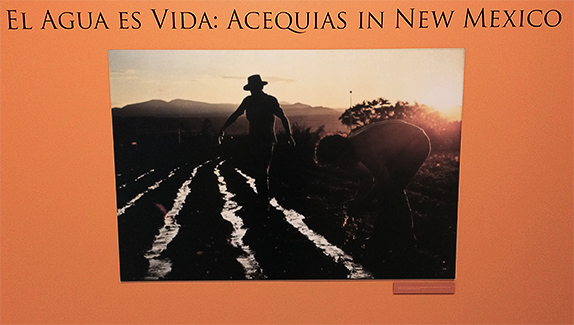

On May 3rd, a new exhibition opened at the Maxwell Anthropology Museum on the UNM campus. Under the title El Agua Es Vida, it takes the visitor on an historical ride through Nuevomexicano rural communities from the arrival of the Spanish to the current crises caused by the pull of outside wage labor, demands for their water rights, and climate change.

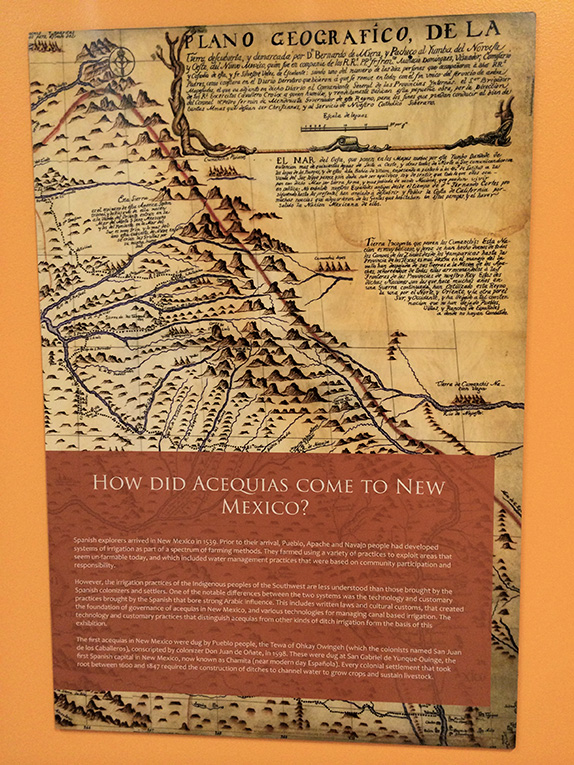

The focus of the exhibit is on the “acequia,” the name for both the traditional irrigation system itself as well as the way of life that it represents. I imagine that most readers of The Mercury will recognize the word. I can also imagine that some will not know that the word comes from the Arabic “as-saquiya” because the Spanish learned the technique from North Africa and brought it with them to the New World. And others may not know that the acequia is a sensitive topic even today, depending on whether or not you believe that the Pueblos irrigated in a similar way before the arrival of the Spanish community-based ditches or not. I doubt that many know that there were already about 60 acequia-based communities in 1700, with about 100 more added in the next century, and another 300 or so during the 1800s. A visitor learns all that from the first few panels as they enter the exhibition.

Displays represent the acequia tradition with a selection of tools that illustrate its practice along with items to give the feeling of how people live then and now. A video shows snippets of acequia work in action today and gives a visitor the feel of why anthropologists like Sylvia Rodriguez, the chief curator for El Agua Es Vida, emphasize “participant observation” as a necessary means to the end of understanding a community. She is a colleague in New Mexican water anthropology, a small world, an emeritus professor at UNM, a native of Taos, and a “parciante” or participant herself in an acequia community in Northern New Mexico. She authored the 2007 book Acequia: Water Sharing, Sanctity and Place.

Some of the interpretive texts in the exhibit are white print on a light yellow background mounted on a yellow wall. At those points reading is difficult. It’s important to do so, though, since the background story is as essential as the objects that represent it. The new water law in 1907 under the territorial government separated water rights from land rights and turned them into a commodity, an incoherent change from a perspective that celebrated “querencia,” a sense of self-defined in terms of landscape. That same law defined the “prior appropriation” system, the one still in effect in many Western states, where in times of shortage those with earliest water rights get all of theirs before anyone else does. This made no sense, either, given the tradition of “repartimiento,” the way of allocating, dividing and sharing water under the leadership of the elected water boss, or “majordomo," and his “commission,” a three person oversight group also required by the Territorial government. Under the repartimiento, water shortage meant sharing based on equity and need, not first come, first served. The new law in the early 20th century set up conflicts that continue to this day.

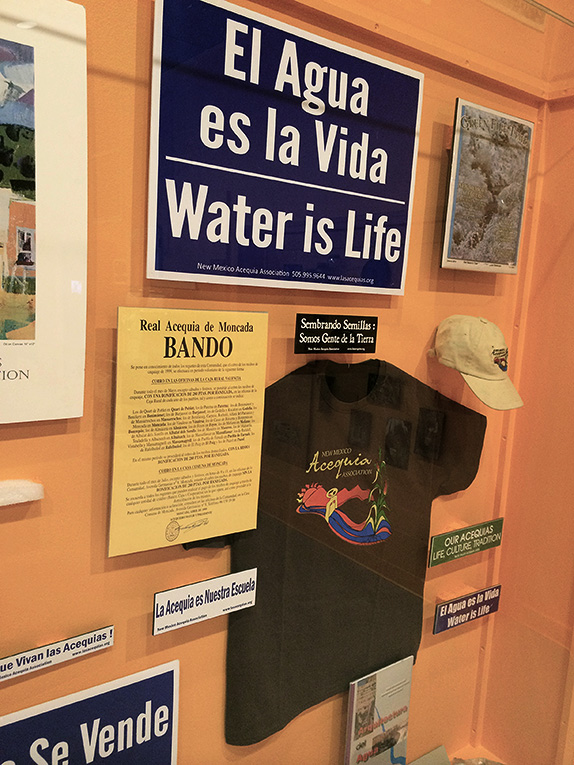

The path through the exhibit ends with contemporary acequia politics and the rise of a grassroots movement formed by several acequia associations, under the banner of the New Mexico Acequia Association, a sponsor of the exhibit. There is talk of increasing crop diversity and sales to local farmer’s markets. Some laws have changed in the acequia’s favor, like the 2003 legislation that gives the community the right to review and approve or disapprove water right transfers to users outside of the community.

I wanted more detail about the current situation, for example whether there are enough young people taking over the acequias and whether they earn a living. This is probably an unreasonable request given the modest physical space allotted to several centuries of history.

The final displays point out that acequias are not the only kind of “autonomous irrigation system” on the planet. In fact, there are many types, scattered across the globe. Prof. Rodriguez was one of the organizers of a conference held at New Mexico State University in 2013 that brought together representatives of such systems from all over the world.

Another display at the exit lists the characteristics of such systems according to anthropologist Paul Trawick. I won’t repeat them here, but many of the items bear an eerie resemblance to some of the key features of "Integrated Water Resource Management." Never heard of it? It’s not a concept you hear much in the U.S., but it’s a global movement with the goal of changing water management for the better. Among other things, it foregrounds local management, water sharing in times of shortage, and sustainable use of water in its ecological context, all features of an acequia system.

Prof. Rodriguez is currently at work on an elaborate study funded by the National Science Foundation, supported by their Coupled Human and Natural Systems initiative. In fact, a co-curator, Prof. José Rivera, author of Acequia Culture: Water, Land and Community in the Southwest, is one of the principal investigators on that project. They’re looking at three acequia communities in Northern New Mexico, considering everything from hydrology to anthropology to computer models. The research itself is displayed in the exhibition, but results aren’t presented and the big question in my mind isn’t answered. Are acequias, in New Mexico, or in other forms called by other names in other parts of the world, in fact sane and sustainable methods that have evolved over time to run small farms in arid environments? I wanted more information about what the study has told/is telling them.

The exhibit is worth a visit and then some. I went in with a fair amount of book knowledge about New Mexico water and acequia communities. For me there was still much to learn from the exhibit, but the main feeling I had as I left was a sense of the profound historical depth and breadth of the New Mexican acequia story, centuries of development with a few critical tipping points, some of them going on right now. The exhibit gives an outsider a hint of what the emotional weight and personal importance of the tradition might feel like to an insider, and it shows the conflicts caused by its placement in today’s global fragmented world. I left wondering what I’d think if I were a kid growing up in an acequia community today. I’ll bet there are many variations on the theme. That, too, would be a fascinating story to tell.

July 01, 2014