Who is there in New Mexico who does not love mountains? Our love affair with our mountains may be because aside from the mountains the land is more drab brown than vivid green, more desiccated than lush. There is not a lot to be said for our flatlands, the Chihuahua Desert landscape of rocks and brush, where what we call rivers are really streams and what we call streams are more often seasonal arroyos.

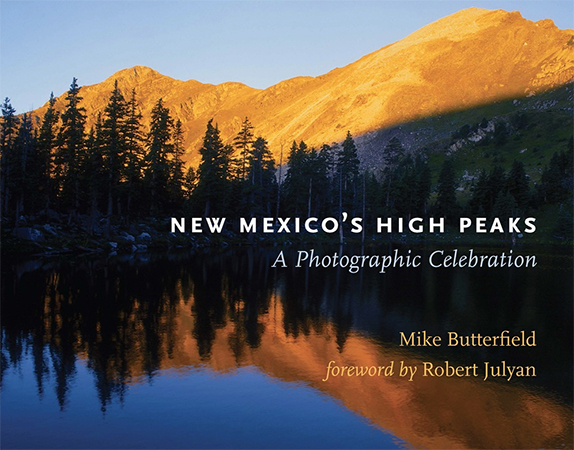

This mountain love affair has spawned a lot of books, of which the newest, and one of the most lavish, is the just-published, New Mexico’s High Peaks: A Photographic Celebration, by Michael Butterfield (UNM Press, $39.95, 188 pages including 134 color photographs).

If, as photographer John Fielder said, “Being there is 90 percent of photography,” then Butterfield is well on his way to excellence. A California musician and Albuquerque jeweler as well as a photographer, he has been hiking and photographing New Mexico’s mountains since he was a teenager 40 years ago. The photographic record of this passion forms the core of this elegant coffee-table volume.

During his life Butterfield has taken a lot of photos of our mountains, many of which appeared in New Mexico Magazine, which published his earlier photography book (written by Peter Greene), Mike Butterfield’s Guide to the Mountains of New Mexico. Published in 2006, it curiously was printed in China.

The new book tackles one facet of our mountains: the gorgeous scenery of the 61 peaks above 12,000 feet (plus one, Sierra Blanca, that has been re-measured at just under 12,000 feet). But our mountains are such complex, precious, to some even sacred places that no one book can really encompass all aspects of them. Butterfield focuses on photographing the stunning scenery of peaks and tarns and cliffs above tree line. Other superb books have focused on the settlements (Mountain Villages by Alice Bullock), the people (Four and Twenty Photographs: Stories from Behind the Lens by Craig Varjabedian), the history and geography (The Mountains of New Mexico by Robert Julyan), the flora and fauna (Field Guide to the Sandia Mountains edited by Robert Julyan and Mary Stuever”) and even paintings (Landscapes of New Mexico: Paintings of the Land of Enchantment by Suzan Campbell and Suzanne Deats).

Whatever the focus, the conclusion is inescapable that the story of New Mexico is in large part the story of its 89 mountain ranges. Of the high peaks described by Butterfield, all but two are on public land and all but one are in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. This chain, which forms the southernmost extension of the Rocky Mountains, extends 200 miles from Poncha Springs, Colo., to Glorieta Pass, just southeast of Santa Fe. Most of the peaks are in the 223,000-acre Pecos National Wilderness or the adjacent Santa Fe and Carson National Forests. The Santa Fe National Forest is the nation’s second oldest.

Despite its large number of mountains, New Mexico is not usually thought of as a mountain state. However, among the 48 continuous states, only California, Colorado, Washington, Wyoming and Utah have higher peaks. New Mexico is deceptive because the base of most of its mountains is a 7,000-foot-high plateau, the highest in the region, fully a thousand feet higher than Colorado’s. Thus a 12,000-foot-high mountain only appears to be 5,000 feet above the surrounding landscape.

But with tree line at about 11,500 feet (the exact altitude depends on whether the slope faces north or south), all of the mountains Butterfield describes have open views of distant mountains and plains. Even from a relative low peak like Sandia Mountain’s 10,600 feet, you can see more than a hundred miles on a clear day.

Butterfield’s book is a beautiful homage to these mountains, where American Indians, Hispanic colonists, Anglo settlers and contemporary hikers have long roamed, played, worshipped, hunted, and communed, as Butterfield eloquently does, with the majesty of the Milky Way above and the grand sweep of New Mexico below. As long as there is a New Mexico, these mountains will continue to obsess us.

April 23, 2014